The ILP played a major role in the anti-war and no conscription movements during the First World War. Many were gaoled, and many abused for their principled, political opposition to the conflict. Yet, not all ILPers became conscientious objectors, as IAN BULLOCK explains.

In retrospect the 1914-18 war became known as the time when the Independent Labour Party was tested and not found wanting, when it stood firm – almost, if not quite, alone – against the evils of militarism and upheld the internationalism of socialism when others flinched and buckled; when it kept the red flag flying. Many of those members who became the most prominent figures in the ILP between the wars – notably Clifford Allen, Fenner Brockway and Jimmy Maxton – were conscientious objectors.

There was enough truth in this image to justify the pride taken, though, as usual, things were a little more complicated in reality. In Inside the Left, published in 1941 in the early stages of another world war, Brockway (left) tells us that there was a spectrum of attitudes to the war within the ILP and that about a fifth of the membership “succumbed”.

One such was Clement Attlee. Unlike his brother Tom, who became a conscientious objector, Attlee joined up, took part in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, was badly wounded in what is now Iraq, and ended the war as a major. This did not stop him returning to the ILP and playing quite an important role in it during its early post-war years.

The war was unexpected. Brockway recalled how he was urged to “talk about Ireland, not Serbia” when he tried to warn of its danger during a speech in Oldham 10 days before hostilities broke out. When it came, the war struck Keir Hardie “like a physical blow and a spiritual blight”, and many of his friends and comrades were convinced that it contributed to his early death in September 1915.

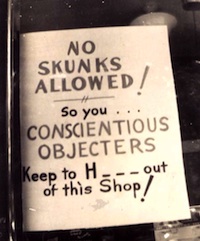

The bulk of the ILP stood firmly against the war but, as Brockway says, “We were not revolutionary socialists. We were democratic pacifists.” Not that this was in any way an easy option. Opponents of the war needed almost unbelievable reserves of courage. And not only moral courage. Brockway tells how, in the early months of the war, he was beaten up by five men after a meeting at Marple. After conscription was introduced in 1916, conscientious objectors suffered horribly – they had never been seen before in a country that had previously relied on volunteers to fight its wars.

It is tempting to give over the rest of this article to their terrible experiences and to the campaigns waged in Glasgow by the Clyde Workers’ Committee and to the gaoling of Maxton for sedition after he had publicly supported the local strike when several of the committee members, including another prominent ILPer, David Kirkwood, were “deported”. But, suffice to say, the No Conscription Fellowship was formed by Brockway and Allen to organise personal resistance to the war. This was one of two important wartime organisations in which the ILP played a key role. The origins of the other went back to before the outbreak of war.

Root of the matter

In the years before 1914 Fred Jowett, a Labour MP and founder member of the ILP, had continually pressed Grey, the foreign secretary in the Liberal government, on whether “any undertaking, promise or understanding had been given to France that, in certain eventualities, British troops would be sent to assist the operations”, and he was told, “The answer is in the negative.” As Jowett told the ILP annual conference in 1917, “The country had been deceived. I had been deceived.”

From 1914 Jowett was one of the many ILPers active in the Union of Democratic Control (UDC) which campaigned against “secret diplomacy” and for peace on the basis of national self-determination and international disarmament after the war had been brought to an end by a just peace. Ramsay MacDonald was a signatory of the letter that led to the UDC’s formation. Its first historian, the former UDC activist and feminist, Helena Swanwick, would later write, “The Independent Labour Party from the first needed no conversion. It had the root of the matter, and from ILP members the Union received some of its best support.”

MacDonald had resigned as chair of the parliamentary Labour Party on the outbreak of war but his position seemed less clear and more equivocal than that of many of his comrades. Writing in the 1950s, Emanuel Shinwell said that “He was neither for the war nor against it.” When he spoke his audiences “heard a man who loathed past wars, regarded future wars with abhorrence, but carefully evaded giving his opinion on the basic question of the current one”.

This did not stop MacDonald being pilloried as an opponent of the war, especially at the “khaki election” of 1918 when he and other ILP MPs lost their seats. Before this the appalling Horatio Bottomley targeted him in his popular John Bull magazine, even going to the length of publishing MacDonald’s birth certificate to smear him as “illegitimate”.

The Woolwich constituency had been held since well before the war by the veteran trade unionist and Labour MP, Will Crooks, and was regarded as a “safe” Labour seat. When ill-health forced Crooks to retire MacDonald looked poised to return to parliament in the subsequent by-election in 1921. But he was defeated by a Coalition-Conservative candidate, Captain Robert Gee, VC.

MacDonald quoted, in the ILP’s weekly, Labour Leader, the comment of a correspondent who tried to reassure him that to have won 13,041 votes while “fighting as a ‘pacifist’ [against] a VC who had killed nine Germans with his own unaided hand, and to have chosen an arsenal as a field of battle, is a miracle”. In another article on the by-election, MacDonald complained, with justification, that, “My private life was soused in a sewer bath. Widows and mothers who had lost sons were told of my night club kind of orgies throughout their racking sorrows.”

MacDonald lost by only 683 votes and many angry members of the ILP and the Labour Party believed the Communists, and their allies in the “Left-Wing of the ILP”, were responsible because of their divisive attacks on him and their campaign for abstentions, although his perceived position on the war was clearly a significant factor.

Turning tide

But the tide was starting to turn and soon a growing proportion of the British people began to recoil from the apparently pointless horrors of the war and to at least consider the possibility that the ILP had been right all along in opposing it.

The Woolwich by-election took place in March 1921. At the general election at the end of the following year the atmosphere had changed sufficiently for many ILP candidates, including MacDonald, to be returned. Within the parliamentary Labour Party there were enough ILPers to secure MacDonald’s success in the leadership election against Clynes, who had served in the wartime coalition government, though only by a margin of five votes.

After the election at the end of 1923 the ILP accounted for 120 of the 191 Labour MPs and MacDonald was able to form the first Labour government. It was, of course, a minority one and Labour was not even the largest party in the Commons, although that changed in 1929 when MacDonald formed his second, ill-fated, government. Clearly, opposition to the war was no longer the electoral curse it had been in the “khaki election” of December 1918.

In August 1922, Minnie Pallister, the ILP organiser for south Wales, was encouraging ILP members to feel confident in asserting how right the party had been. “We were right on the War. We were right on the Peace. We were right on Reparations,” she proclaimed on the front page of Labour Leader. Just before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the ILP, which had disaffiliated in 1932, looked poised to rejoin the Labour Party – but war intervened and once more the ILP opposed it.

But by 1949, an equivalent period after the end of the hostilities to the appearance of Pallister’s article, few thought that, in retrospect, the ILP had been right. The 1939-45 war seemed to most to have been a grim necessity, even a ‘people’s war’. But then, as the example of Attlee shows, there had been some on the left who believed that in 1914.

—-

Ian Bullock writes about the relationship between socialism and democracy. He is the author of Romancing the Revolution: The Myth of Soviet Democracy and the British Left, and co-author, with Logie Barrow, of Democratic Ideas and the British Labour Movement, 1880-1914.

Also see Ian Bullock’s ‘What Can We Learn from the Inter-War ILP?’, plus ‘A Living Wage: A Policy with History’, and ‘Disaffiliation and its Aftermath’.

His profile of Fred Jowett is here

We aim to publish a series of articles in 2014 on the ILP and the anti-war movement during World War One. See: ‘Remember Those Who Refused to Fight’.

11 November 2018

[…] James, was also a socialist. Less taken by the fight against the Boche and a member of the ILP, which had a strong anti-war sentiments, he was swept up by […]

10 November 2018

[…] James, was also a socialist. Less taken by the fight against the Boche and a member of the ILP, which had a strong anti-war sentiments, he was swept up by […]

5 August 2014

I take Keef 69’s point that as people could only remain active in the Labour Party via one of its affiliated organisations up to 1918, the pro-war advocates in the ILP had a difficulty in continuing to pursue their socialist values within the Labour Party if they resigned from it during the First World War. Yet there were numbers of ILPers such as the two I mentioned (Jack Lawson and George Bloomfield) who had a clear alternative avenue to work through, which was also affiliated to the Labour Party. In their case it was the Durham Miners’ Association (DMA), which was part of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain. They were prominent and highly active within the DMA and used it to push for democratic socialist values – before, during and after the First World War.

The work of “The War Emergency Workers’ National Committee” (which was established the day after Britain joined the war), also shows the way which pro and anti-war advocates could still co-operate on ways to safeguard working-class interests, during the conflict. After the first rush by many working class people to join the army, changes occured which made the case of those who had opposed the conflict more acceptable. For there were deaths, casualties, conscription and industrial exploitaion; which all reshaped people’s attitudes – even when they did not become anti-war. These matters effected many in the Labour Party apart from ILPers. So Ramsay MacDonald who resigned from the Leadership of the Labour Party (then being the Chairmanship of the PLP), relatively soon returned as Leader and became Labour’s first Prime Minister. Divisions in the Labour Movement over the war were also put to rest after the war, when there was a concentration on the continuation of the industrial unrest.

A biography of Jack Lawson is being worked on, so his own feelings at the time may be revealed, for he does not cover the issue in his own autobiography.

27 July 2014

I think what Harry Barnes misses in relation to how pro- and anti-war sections of the ILP could still stick together is that they had nowhere else to go. If you were a politically active Labourite at the time, the ILP was your party. *There were no constituency Labour Parties until 1918.* Therefore, unless you wanted to opt out of political involvement altogether, you had to muck in with folk with apparently dramatically opposing views or get out altogether.

I think it is also important to consider why the ILP opposed the war. The official line in the Labour Leader was not the ethical-pacifist one you’d expect. Rather that the war was *undemocratic* (secret diplomacy and Russian autocracy) – see, eg, the Labour Leader for August 13th, 1914. Therefore, in other circumstances the ILP could have supported the war. With that underlying notion that a war can be a ‘just war’, it is not surprising that some considered the ongoing one to be just that. The opposing factions become with this in mind rather less at odds than they might first appear.

15 February 2014

Harry’s account of Jack Lawson’s experience, and of the swing to Labour in Durham at the county council elections, reinforces the point I was trying to make in the orginal piece about how fairly soon after the war there was a “turning of the tide”.

Hope you enjoy ‘Democratic Ideas’, Harry, when you have time to read it. Just so you know who to blame (most), although we of course stand by the book as as whole, the ‘political’ bits are based on my D Phil research at Sussex Uni and the ‘industrial’ ones on Logie Barrows work.

The Blair years dilemma you describe is familiar, even to a pretty inactive LP member like me. It seemed like every few weeks – every few days, even, post-Iraq – I would be trying unsuccessfully to persuade someone I knew not to resign from the party. My constant cry was, “all the wrong people are leaving the Labour Party”, which, for me, was borne out by the fact that David Miliband ended up with a majority of members’ votes in the leadership election.

All power to your elbow – I shall now have a look at the blog

Ian

7 February 2014

Ian. When Jack Lawson stood for the Seaham Constituency in 1918, he had just fought in the First World War. But he immediately opposed reparations, because he saw something of the disruption they would lead to. This perhaps shows something of the compromise which could be made by him with those in the ILP who had taken an anti-war line. He lost the seat to the sitting member for the preceeding South East Durham seat. This was Evin Hayward, a Liberal who was a Major in the war. In the Khaki election, Jack’s anti-repartion stance probably told against. Hayward was also popular amongst the Miners and on the basis of their ballot addressed the Durham Miners Gala in 1913. Hayward beat Lawson in a straight fight, although he had refused to take the “coupon”. Yet it was a straight fight. Within a few months County Durham swung much further to Labour and tney captured the County Council. The first County to ever go Labour. If there had not been a rushed post- war election, then Lawson would probably have won, the seat. Shortly afterwards he won a by-election in Chester-le-Street.

I have just obtained a second hand copy of your book “Democratic Ideas and the British Labour Movement 1880-1914”. It is a former Kent Library copy and is in fine condition – even though it was borrowed regularly between 1997 and 2002. I am deep into another project at the moment, so it I will have to leave reading it for now. But you cover a fascinating topic over a key period.

On Blair and cynicism, I was in the thick of the problem as a Labour MP at the time. The problem was that a voter from Clay Cross during the 2001 election asked me “How can I vote or you Harry, without voting for Blair ?”. Even with a 10% rebellion rate, I could not answer his question to my own satisfaction. Check my blog for my lastest bit of grumpyness – http://threescoreyearsandten.blogspot.co.uk/

5 February 2014

I too am an “old cynic” who stuck “with the Labour Party even after Blair’s role in the invasion of Iraq, and I couldn’t agree more with what you say, Harry, though I’m not at all sure I can throw much light on why people who took radically different positions on the war managed to work together soon afterwards. All I can suggest is that whether you supported the war and participated in it, or opposed it and became a CO, etc, you had in common a knowledge of its horror and a belief that it should have been avoided, as should, most definitely, future wars. In most cases also I suspect that whichever “side” you’d been on you recognised that the people on the other were acting from the best motives. My own feeling about WWI is “Thank God I wasn’t around at the time and had to take a decision on what to do.”

It’s interesting that even in the ’30s some in the ILP – well, at least one – saw a possible problem over members, or in this case potential members, who had taken different stances on the war 20 years earlier. When the ILP disaffiliated one of its newer and very high profile recruits was John Middleton Murry, a prolific writer and critic, nowadays chiefly remembered as the widower of Katherine Mansfield, and editor and promoter after her death of much of her work. He wanted the ILP to adopt a “revolutionary policy” but definitely not one that had anything in common with that of the CP. In a memo he wrote on the “organisation of the new ILP” he looked forward to an influx of new members. He wrote that many recruited into the new ILP would be “men who served in the Great War, the surviving remnant of the idealistic volunteers of 1914. Any suggestion that these men were in any respect inferior to the pacifists must be strenuously avoided. Individualistic pacifism may have consorted well enough with the ‘evolutionary’ Socialism of MacDonald and Allen; it does not consort with revolutionary Socialism.” An appendix concluded that both pacifists and those prepared “to fight, in the literal sense” might be reconciled on the basis of training for “disciplined non-resistance”.

Murry himself had been neither an opposer nor an active participant in the war.

Ian

4 February 2014

Ian: How the ILP came out of the First World War is astonishing. After ILPers went in different directions over the First World War itself, many remained together in the organisation and were soon afterwards fighting together politically on a fairly united front. Jack Lawson, for instance, was active in the ILP and fought in the First World War. He did this without needing to be conscripted. Then in 1918, he unsucessfully fought the newly founded Seaham Constituency for Labour. His main backing and organisational support came from local ILP branches and from miners’ lodges, many of whose leading officials were local ILP activists. His agent, George Bloomfield had been a fellow radical ILPer in the Durham Forward Movement before the war. As a war-time local Labour councillor, Bloomfield even attempted to have two JPs removed from their positions because they had German sounding names. Yet there was no major walk out from the ILP over MacDonald and company taking an anti-war line. Pro- and anti-war elements had, of course, worked together throughout the war in the War Emergency Workers’ National Committee, by concentrating on workers’ social, industrial and economic interests. Then, especially, in mining communities the whole political situation was transformed quickly once the khaki election was out of the way – via the events that led to the setting up of the Sankey Commission. But are such things enough to explain how many ILPers with different attitudes to the war stuck together? It can’t just be like having old cynics such as myself sticking with the Labour Party even after Blair’s role in the invasion of Iraq. Labour and especially ILP activists where much more idealistic some 100 years ago. Is there a key influence at work that I am missing? Then MacDonald is Prime Minister only five years after the end of the First World War. His equivalent in only a slightly longer period after the Second World War was (much less of a surprise) Winston Churchill.