3. Labour’s Rise & Disaffiliation

Labour’s Rise

From 1918 Labour’s star was in the ascendant. Within four years it held over 140 parliamentary seats and it began to eclipse the Liberals. Other factors lay behind Labour’s rise. In 1918, under the influence of both Sidney Webb, the leading Fabian, and Arthur Henderson, the Labour Party secretary, Labour’s organisation was transformed.

From a loose electoral alliance it became a more tightly-knit machine based in the localities. Individual part membership was regularised, removing the need to join through affiliated bodies.

To overcome trade union leaders’ unease about the new local parties becoming too radical, they were accorded even greater power. Trade unions were to have control of the elections to an enlarged national executive and the separate places for affiliated socialist societies were eliminated.

In completing the reform package and to show that Labour had a sense of purpose, the party adopted Sidney Webb’s famous Clause IV, the call for the collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange. However, as he rather pointedly explained, his intention was to transform “the Labour Party from a group representing the class interests of manual workers into a fully constituted political party of national scope, ready to take over the government of the country”.

The changes also had a major impact on the ILP. Deliberately so, as both Labour Party and trade unions leaders were determined to ‘fix’ the left after the war. In many areas, the new local Labour parties began to siphon off many activists. No longer did the ILP hold a seat on the national executive, although some ILPers continued to hold seats in the divisional Labour Party section.

Following the party’s constitutional changes, some right-wing ILPers questioned the continued relevance of the ILP. For example, Philip Snowden MP, argued that the ILP had served its historical purpose. The left disagreed, arguing that the ILP was need to act as a socialist pressure group within the Labour Party.

For a time the ILP’s political dilemma about its role in the restructured Labour Party was resolved by the rise of Clifford Allen. An upper class intellectual with great financial skills, he sought to turn the ILP into a high-powered influential policy-making body. Having served three years imprisonment for refusing war-time conscription, he was able to secure financial support for the ILP from middle-class, pacifist sources.

Allen argued: “We must state the case for socialism so convincingly that all people of intelligence and goodwill will turn to it…if the ILP can become the instrument of such a policy, it will sweep all before it.”

As chair of the ILP, he gathered an impressive array of radical intellectuals around it. He relocated the ILP’s head office to palatial surroundings, established research and information departments, and revitalised the flagging Labour Leader newspaper which became New Leader (1922) with a highly paid editor. In addition, the ILP summer schools were transformed into largely middle-class assemblies.

He also cultivated his friendship with Ramsay MacDonald, who had been restored to the Labour leadership after the war which he too had opposed. When MacDonald became Labour’s first prime minister in 1924, Allen was a regular visitor to Downing Street.

However, Allen failed to persuade MacDonald or the Labour Party to set up commissions to prepare detailed schemes of socialist construction for when Labour was in office. So he encouraged the ILP to do so instead. The first commission, on agriculture, included the call for the nationalisation of land. Promoted by the ILP, it was adopted by the Labour Party conference.

However, Allen failed to persuade MacDonald or the Labour Party to set up commissions to prepare detailed schemes of socialist construction for when Labour was in office. So he encouraged the ILP to do so instead. The first commission, on agriculture, included the call for the nationalisation of land. Promoted by the ILP, it was adopted by the Labour Party conference.

But the commission attracting the most attention did not gain Labour’s support. Socialism in Our Time or The Living Wage (as it was also known) was to become a precursor to Labour’s reforms two decades later. It called for the immediate introduction of a fixed minimum wage for all industries and for family allowances. To provide for these the banks, mines, land, electricity and transport were to be nationalised. Any essential industry failing to comply with the minimum wage was also to be taken into public ownership.

To Allen’s dismay MacDonald instantly repudiated Socialism in Our Time as “flashy futilities”. This left Allen in a much weakened position in the ILP. Ironically, the policies formulated by his commissions contributed to his downfall. They formed part of the growing shift to the left in the ILP and they widened the rift with the Labour Party.

Fenner Brockway, then ILP general secretary, gave three reasons for Allen’s fall and Jimmy Maxton’s rise: “First the ILP was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the MacDonald leadership of the Labour Party, particularly after the first Labour Government of 1924. Second, the rank and file outside of London, which remained proletarian, became impatient with the middle class domination of Head Office and the grand scale of its up-keep. Third the membership having accepted the Socialism in Our Time plan seriously, were in a mood to challenge aggressively the gradualism of the Labour Party.”

Growing Divide

Spearheading the criticisms of Allen’s leadership were the militant Clydeside MPs, including Jimmy Maxton and John Wheatley. Under their influence, the ILP embarked upon a more confrontational course with the Labour leadership.

A fierce and fine orator, and a deeply committed and incorruptible socialist, Jimmy Maxton reasserted the party’s class politics. He confirmed the growing conviction of many ILPers that the Labour and trade union leaderships were becoming obstacles to socialism.

During the 1926 General Strike and miners’ lockout, which the Labour leadership found deeply embarrassing, the ILP published The Miner for the impoverished mineworkers’ union, selling 90,000 copies weekly. Following the miners’ betrayal and abandonment by the TUC, Maxton and the miners’ General Secretary, Arthur Cook, himself an ILPer, published a joint manifesto denouncing all forms of class collaboration. The Cook-Maxton Manifesto, coupled with the campaign for Socialism in Our Time, which was regularly defeated at Labour Party conference, made the ILP increasingly unpopular with the Labour leadership.

These differences of political strategy came to a dramatic climax with Labour’s return to office in 1929. MacDonald’s main aim was to show that Labour was ‘fit’ to hold office. Given that the Liberals held the voting balance in the Commons, he was only prepared to introduce measures which they would find acceptable.

As a result of this approach, the minority Labour government soon found itself in deep trouble with its own supporters. Unwilling to challenge the capitalist system, the government soon fell victim to the pressures of a capitalist recession. Public expenditure was cut repeatedly, unemployment soared, and the working class was made to bear the brunt of the crisis.

The ILP’s case, which MacDonald dismissed as mere romanticism, was that a Labour government should stand or fall by a radical programme. First, it should introduce expansionist popular measures and, at the point when the Liberals blocked further changes, the Government should campaign with the slogan: “The people versus the banks”.

In vain, the ILP rebels in the Commons mounted a desperate resistance to the government. The remainder of the Parliamentary Labour Party dutifully voted as instructed, obeying the call to “Trust MacDonald”. In desperation, the ILP’s executive announced that its 140 MPs must take the ILP’s whip and not the Labour government’s. Most refused and 123 MPs were expelled.

These divisions bit deep into the ILP itself. In Scotland the ILP branches condemned Maxton for voting against the government by 103 votes to 94, although the ILP nationally upheld ‘the rebels’.

As the economic crisis deepened – and as the labour movement became more resistant – Ramsay MacDonald and the chancellor, Philip Snowden, defected. In consultation with King George V, they collaborated with the Tories to form a national government, sending shockwaves through the Labour Party, but it did nothing to heal the rift with the ILP.

Disaffiliation & its Effects

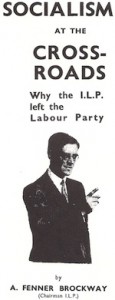

The specific issue which triggered the ILP’s disaffiliation from the Labour Party was a heated debate on the relationship of the ILP MPs to the Parliamentary Labour Party. In the aftermath of the conflicts with the MacDonald leadership, the new Labour leadership insisted that ILP-sponsored MPs should now be subject to the same parliamentary whip as Labour MPs. The ILP refused.

But, as we have already shown, the roots of the conflict lay much deeper. They relate to the frustration that different generations of socialists have often felt about Labour’s lack of radicalism.

In its early years, ILPers had hoped that by creating and sustaining the Labour Party, in alliance with the trade unions, they could reach the working class and win them to socialism. By 1932, at an emotionally-charged, special conference, this approach was rejected. The branches voted to disaffiliate by 241 votes to 142.

In its early years, ILPers had hoped that by creating and sustaining the Labour Party, in alliance with the trade unions, they could reach the working class and win them to socialism. By 1932, at an emotionally-charged, special conference, this approach was rejected. The branches voted to disaffiliate by 241 votes to 142.

Support for the break came from a younger generation of working class activists, angry and dismayed at the shameful record of the MacDonald minority government. Disaffiliation had significant consequences for both parties. With the ILP’s departure, the Labour Party became more manageable. The right wing were well placed to strengthen their hold, to keep down the remaining left forces and to direct the party how they wished.

Following MacDonald’s defection, Labour suffered badly in the general election. In response, trade union leaders decided to exert greater control over the party, rather than to trust the parliamentarians as they had done in the recent past. The union leaders’ efforts were made easier because the parliamentary party was in a weaker position, numerically and politically.

But what really strengthened the unions’ grip was the changing nature of the block vote. To survive the recession, the unions were merging into big general unions where power was concentrated at the top. With their massive voting strength they could, if they chose, dominate the party organisation.

Men like Ernest Bevin, head of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, began to shape Labour’s future. An alliance was constructed between ‘moderate’ parliamentarians and trade union barons that was to last for decades. The block vote became the property of a handful of trade union leaders who placed it at the disposal of right-wing Labour leaderships.

Bevin dismissed the ILP, saying that they “let their bleeding ’earts run away with their bleeding ’eads”.

For a time, the internal opposition to the Labour leadership and trade union control came from a regrouping of Labour lefts with former ILPers. Together, they set up the Socialist League but it never had the chance to establish a sizeable grass roots base along the lines of the earlier ILP.

Under the somewhat eccentric leadership of Sir Stafford Cripps (who foundered the newspaper Tribune in 1937), the Socialist League came into conflict with Labour’s tough-minded national executive. Eventually the executive expelled Cripps and proscribed the Socialist League (although Cripps was later returned to become a most conventional, post-war chancellor of the exchequer). The League disbanded.

It was not long before the ILP’s high hopes about the advantages to be gained from the split with Labour began to ebb. At first, with unemployment at record levels, with Labour’s electoral decline, and with growing international tensions relating to the rise of fascism, many ILPers had thought that a golden opportunity was at hand. For them, the crisis of capitalism was drawing near. They believed that free from the constraints of a compromised and discredited Labour Party, the ILP would be well placed to drive home the socialist message.

The membership figures for these years tell another story, however. Within four months of the fateful decision to leave, the ILP had lost one-third of its branches. Membership, which had stood at 16,773 in 1932, fell annually. By 1935 it had fallen to 4,392. Three-quarters of the membership were lost in three years.

The Socialist League did not gain many recruits from these losses. Nor did the Communist Party, even though a pro-communist group in the ILP, the Revolutionary Policy Committee, had campaigned hard for the ILP’s break with Labour. Its members joined the Communist Party three years after the ILP’s disaffiliation.

—-

This is an extract from the original centenary edition of The ILP: Past & Present, published in 1993. The print version is now sold out.

This is an extract from the original centenary edition of The ILP: Past & Present, published in 1993. The print version is now sold out.

The latest revised and updated version, published in 2023 to mark our 130th anniversary, is available to buy in two parts from our publications section.

15 September 2016

Great goods from you, man. I have have in mind

your stuff prior to and you are just too great. I really like what you’ve obtained right here, really like what you are saying and the best way by which

you are saying it. You are making it enjoyable and you continue to take care of to keep it wise.

I can not wait to learn much more from you. This is really a wonderful website.