GRAHAM TAYLOR celebrates the life and achievements of Alfred Salter, the brilliant doctor, Bermondsey MP and lifelong ILPer who helped to transform an impoverished corner of south east London.

The life of Dr Alfred Salter is chiefly known to the world from a book Fenner Brockway published, to great acclaim, in 1949. Hailed as a classic of political biography, Bermondsey Story describes in moving terms how in 1899 the young Salter dedicated his life to the impoverished people of Bermondsey, a slum area overrun by squalor and disease in the south east of central London.

Brockway informs the reader that back in the 1890s Salter was the most brilliant medical student ever to study at Guy’s Hospital, to which he had won a scholarship from Roan School in Greenwich at the age of 16. At Guy’s he staggered teachers with his boundless energy and photographic memory. He took a triple first, with gold medals, at the early age of 22, and at 24 was accepted for postgraduate research into bacteriology at the prestigious British Institute of Preventive Medicine. By the time he was 25, his research into diphtheria was known all over Europe.

It was a moot point whether he would become an extremely rich Harley Street consultant, with a mansion in his beloved Kent, or instead make a breakthrough in the study of infectious diseases and go down in history with Joseph Lister or Louis Pasteur. He had a choice between fame and fortune.

It was a moot point whether he would become an extremely rich Harley Street consultant, with a mansion in his beloved Kent, or instead make a breakthrough in the study of infectious diseases and go down in history with Joseph Lister or Louis Pasteur. He had a choice between fame and fortune.

Instead, says his biographer, he rejected both options. Appalled by the slums of Bermondsey, often lacking in basic amenities such as heating and running water, he decided to dedicate his life to the welfare of the poor. He rented rooms in Bermondsey and there set up a general medical practice. Other doctors joined his philanthropic enterprise. The practice treated poor patients at a cheap rate and treated the poorest for free.

Salter’s insight was that in slum conditions, where the unemployed or disabled might starve to death unless some charity were at hand, decent housing and food were themselves ‘preventive medicine’. To campaign for better conditions, he joined the Liberal Party and its London offshoot, the Progressive Party (an alliance of Liberals with Radicals and Fabian socialists). He was elected a Bermondsey borough councillor in 1903, then a London county councillor in 1906. Later, in 1922, he was elected as Labour MP for Bermondsey West.

Between 1922 and Salter’s death in 1945 Bermondsey was transformed by what is often termed the ‘Bermondsey Revolution’. Brockway describes how Salter introduced a local health service for the poor long before there was a national health service. This service deployed the latest medical innovations, such as a solarium for victims of tuberculosis, and utilised the latest methods of health education, such as documentary films shown in the streets on the back of vans.

With his wife, Ada, an expert on gardens and ‘garden cities’, Alfred organised a massive programme of slum-clearance. They replaced the slums with model council housing in cottage style, with gardens at front and back, with light and spacious rooms, and with facilities inside checked for utility and convenience by working class women, not left to the decisions of architects.

Tragic setback

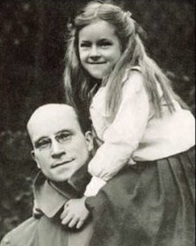

The couple had one tragic setback. In 1910 their only child, Joyce (below), fell victim to one of the epidemic diseases that regularly swept through the slums. The form of scarlet fever Joyce contracted was too virulent even for her father to cure. If Alfred had opted for research in leafy Sudbury at the Lister Institute, or bought a mansion in Kent, Joyce may have been spared.

Joyce’s death, says Brockway, created a legend in Bermondsey. The couple could easily have sent their daughter off to boarding-school but, convinced that the family must participate fully in the hardships of the people, they had Joyce educated at the local school. To this day, as Brockway says, the memory of the Salters is revered by everyone in Bermondsey, regardless of their political party or religious persuasion.

Nonetheless, Brockway’s inspiring tale was one-sided. In portraying the Bermondsey revolution of the 1920s as if it were the work almost of one man, Brockway inevitably obscured the movement from which it sprang. In his account, the work of the Methodists and Liberals in Bermondsey before 1922, and the input of the women’s movement, the trade union movement and the environmentalist movement became almost invisible.

Brockway’s biographical approach even sidelined the role of the ILP, the party to which both he and Salter had belonged. It is hard to appreciate from what he writes that ILP leaders were introducing similar reforms to Bermondsey’s (although not on the same scale) throughout the north of England and across the river in Poplar.

Take as an example a booklet entitled Twelve years of Labour Rule in Bermondsey that the Bermondsey Labour Party published as an election manifesto just before the borough council elections of 1934. There was a preface by Salter in which he highlighted the council’s achievements since 1922. He described how experts were now coming to Bermondsey, not only from all over Britain but from all over the world to learn about Bermondsey’s ‘transformation’.

The visitors included: “Housing experts, Public Health experts, Beautification experts, Gardening Experts, Town Councillors, interested enquirers”. Salter noted that in 1922 Labour had won 27 out of 54 council seats; in 1931 it was 45 out of 54. He called for 54 out of 54. The voters obliged. Labour won every council seat in the elections of 1934.

This was obviously a staggering political achievement and Salter was undoubtedly the dominant personality in Bermondsey’s politics, but 54 seats out of 54 are not won just by a dominant personality. The leader of Bermondsey council in this period was Bill Cragie, a trade unionist with huge local support. The visitors from all over the world would be talking not only to Salter, the MP, but to Cragie, or one of many other talented councillors, such as Ada Broughton or Jessie Stephen, ex-suffragettes, or to Ada, Alfred’s wife. Salter was not even an elected councillor, only an alderman, and his time was mostly taken up in his capacity as MP.

The ILP ‘religion’

It was the ILP which brought together all the elements of Bermondsey’s municipal revolution. Its ethical socialism united Christians, humanists, trade unionists, feminists and environmentalists. It was not so much a political party as a religious or, at least, an idealistic movement. When Herbert Morrison was hauled up, as a conscientious objector, before a war-time tribunal he was asked to give his religious denomination. He replied: “I belong to the ILP and socialism is my religion.”

Alfred and Ada (below) loved the ILP, both as Quakers and as socialists, and their best achievements, apart from his work as a doctor and her work as a social worker, were as leading members of the ILP.

It is true that a Bermondsey branch of the ILP was not formed until 1908 but in spirit the Salters had belonged to the ILP long before. The ILP was weak in London until after 1906, and anyone who wanted to make any political progress had to join either the Progressive Party or the Social Democratic Federation.

Not only that, but before 1906 Bermondsey and Rotherhithe were solidly Conservative and it was hard enough to elect Liberals, let alone Labour. From 1906 all this changed when, on the one hand, many ILP candidates were elected to parliament while, on the other, the new Liberal government was slow in delivering its promises. There was special resentment in Rotherhithe where the Liberal MP, Carr-Gomm, was opposed to women’s suffrage.

The Salters were impressed by three measures in particular that the ILP had campaigned for but which the main body of Liberals were reluctant to grant: free school meals, old age pensions and unemployment benefit. All these, since there was at that time no welfare state, were essential in Bermondsey to prevent malnutrition, disease and starvation. Of course, there were Liberals who were prepared to progress these measures, such as Lloyd-George, but other leading Liberals, such as Asquith, demurred.

Salter became chair of the Bermondsey ILP in 1908 and remained chair to the end. It was from the ILP that he gained the political strength for his two greatest achievements, his contribution to Bermondsey in the 1920s (especially in public health and in the related issue of housing) and his work in defence of conscientious objectors in World War I. The first came from his experiences as a doctor, the second from his commitment as a Quaker, but in both cases it was through the ILP that his work was politically effective.

Alfred had joined the No-Conscription Fellowship in 1916. Its aim was to encourage men opposed to war to refuse to serve in the armed forces and he soon founded a Bermondsey branch. Most members were in the ILP. This was dangerous work. In 1914, there had been an earlier anti-war organisation, called the Union of Democratic Control, but as Bertrand Russell (another ILP member) said, that was a very “mild” affair. Those in the NCF risked being physically attacked, or being sent to prison, as Russell was.

For Salter and the ILP it was not just a question of pacifism but of civil liberties in a democracy. Their argument prevailed. In World War II so convincing had been the work of the NCF in World War I that anyone who showed they had a genuine objection to war was accepted and without much ado offered alternative work. In World War I, COs had been put in prison, beaten up, tortured, and sometimes shot.

Alfred’s fortunes were tied to the ILP. When the ILP went down, Alfred went down. He had nervous breakdowns when the ILP was in disarray. When the ILP crumbled during the First World War and in its aftermath, Salter was sorely distressed. He said that for a while “it seemed as if the whole fabric of our organisation so laboriously built up in the past years, was doomed to go under”. In the late 1920s he was in despair when the ILP, under Maxton and Wheatley, took an ultra-left course he could not follow. The disaffiliation of the ILP from the Labour Party in 1932 was for Salter a personal tragedy.

Without the compass of the old ILP Salter cut a solitary figure in the 1930s, pursuing ‘left-wing appeasement’ and increasingly remote from what Ada and her friend, Eveline Lowe, were achieving on the London County Council. He clung to his icon, George Lansbury, but in 1935 went down with him at the hands of Ernie Bevin.

After Ada’s funeral, at the Quaker meeting house in Peckham in 1942, Alfred marvelled at the beauty of the service and how well it expressed Ada’s selfless devotion to the people, but he wrote: “it was a renascence of the old ILP spirit, now, alas, gone apparently for good.”

Salter would have been pleased to know that his achievements are still cherished in Bermondsey. Even ideas of his which seemed to have failed completely – his rejection of high-rise flats, his opposition to all wars, his campaigns against drunkenness, his advocacy of co-operatives, and his refusal to pay taxes for faith schools – are still the subject of keen debate.

But, above all, one suspects, he would have been pleased to know that the 120th birthday of the ILP is being celebrated in 2013. He would like to have been present at any celebrations, doing his famous party tricks and roaring with laughter at the jokes.

—-

Graham Taylor is a retired history lecturer. He writes about labour movement issues and was co-author with Jack Dromey of Grunwick: the Workers’ Story published by Lawrence & Wishart in 1978.

‘Dr Salter’s Daydream’, Diane Gorvin’s 1991 statue of Alfred Salter waving at his daughter, Joyce, was stolen from outside the Angel Pub near the River Thames in Bermondsey in November 2011. The Salter Statues Campaign was set up by local residents, including the Salters’ great niece, to raise £100,000 for a new monument to Alfred and Ada. To find out more and make a donation go to: www.salterstatues.co.uk

More ILP anniversary profiles can be found here.

10 August 2015

Just a personal note. The suffragette, Ada Broughton was my great aunt. I never knew her as she died around 1934 well before I was born. My late mother, Irene Grigsby, knew her well when she was a child and spoke about her a lot, but I don’t know how much was true and how much Mum’s invention. Have you any material on her?

17 March 2015

[…] Graham Taylor’s profile of Ada Salter is here and Alf Salter’s story is here. […]

14 November 2014

[…] Salters’ story is an almost forgotten gem of Labour history, telling how the brilliant doctor, Alf Salter, and his campaigning wife, Ada, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, a slum area […]

30 September 2014

[…] Salters’ story is an almost forgotten gem of Labour history, telling how the brilliant doctor, Alf Salter (left), and his campaigning wife, Ada, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, a slum […]

10 July 2014

[…] Alfred Salter (1873–1945), who created the original local […]

11 November 2013

[…] was at the Bermondsey Settlement that Ada met Alfred Salter in 1898. He was a career doctor ambitious for research, fame, fortune, and perhaps a mansion in […]

29 March 2013

What a truly inspiring life story. It seems that Alfred and Ada Salter were very remarkable and special people who lived their lives in line with their religious and political beliefs. What great role models and how very different people they were from many present day Labour leaders and MP’s who’s socialism seems to be skin deep and primarily based on career ambitions.

While the ILP today is small, I am struck also by the symmetry of what ILP tried to do all those years ago in Bermondsey insofar as “It was the ILP which brought together all the elements of Bermondsey’s municipal revolution. Its ethical socialism, united Christians, humanists, trade unionists, feminists and environmentalists”, and the political perspective of today’s ILP, which is also non-sectarian and inclusive.