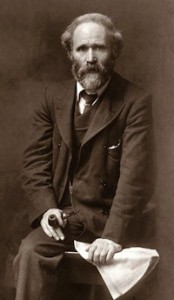

PAUL SIMPSON examines the life and politics of ILP founder Keir Hardie, uncovering staunch principles, distinct traits and personal contradictions.

Let me start with a brief biography. James Keir Hardie was born in Lanarkshire in Scotland in August 1856. At seven he began work as a message boy and by the age of 10 he was working in a mine as a trapper, one of the boys who opened doors to let a coal cart through. At 17 he signed the temperance pledge.

Hardie first became involved in politics through trade union activities, which began at the age of 22 and saw him become secretary of the newly created Ayrshire Miners’ Union in 1886. He was at this time a self-professed Liberal supporter and sought nomination to stand as a Liberal candidate in 1888. When he was rejected, he stood as an independent labour candidate, which also proved unsuccessful.

He helped form the Scottish Labour Party in 1888 and was elected to Parliament as MP for South West Ham in 1892, a year before the Independent Labour Party was founded in Bradford on 13th January 1893. He lost the next parliamentary election in 1895 but was returned for Merthyr in 1900, remaining in that seat until his death in 1915.

Hardie’s first encounter with socialism was in 1887 when he went to London intending to join the Social Democratic Federation. He decided against it, and in 1900 the ILP joined with other parties to form the Labour Representation Committee which later became the Labour Party.

Hardie opposed the British military campaigns against the Boers and from 1903 onwards worked with the Women’s Social and Political Union in campaigning for female suffrage. In 1907 he embarked on a ‘world tour’, visiting North America, India and Australia.

From 1912 Hardie agitated unsuccessfully for a general strike in Britain and Europe in the event of war. He died in September 1915 with the world war still raging.

Feminism and women’s equality

Hardie dedicated much of his political life to issues surrounding the status of women in British society. His questions and speeches in the House of Commons, his journalism and his political writings all provide ample evidence of his genuine interest in women’s equality.

It is a striking characteristic of Hardie’s politics that he often viewed events with a ‘feminist slant’. For example, he attacked the institution of the monarchy by complaining that Queen Victoria’s jubilee celebrations made no mention of the fact that she was a woman, and he jeopardised his standing in the Labour Party by championing votes for women.

The main focus of Hardie’s efforts was his support for the extension of voting rights to women. Hardie wrote that he wanted to confine himself to this “one question of … political enfranchisement”, arguing that “the woman question as a whole” was “beyond the scope” of his ability. Whether this was because, as a man, he believed he had no right to suggest a definitive solution, or whether he felt it was beyond his intellectual capacity, it is difficult to know. It is tempting to lean towards the former notion, as it is apparent that he saw voting rights as essential precisely because they would enable women to shape their own destiny.

In an article entitled ‘The Citizenship of Women: A Plea for Woman’s Suffrage’ he argued that issues such as marriage laws and economic inequality could only be dealt with satisfactorily once women had the vote and were in a position to “influence equally with men the creation of opinion”.

Secondly, by focusing on the issue, Hardie revealed a level of political pragmatism. He described female enfranchisement as an issue “ripe for settlement by legislation” and demonstrated a complete willingness (at least until 1906) to work with the Liberal Party.

It could also be argued that Hardie made a deliberate effort to win over the Tories. For instance, he cited a speech by Benjamin Disraeli in which the former Conservative prime minister outlined the reasoning behind his support for the enfranchisement of women. And he reassured conservatively minded people that “in those countries where rights of citizenship have been conferred on women, there has been no great and sweeping change either in policy or legislation”.

What’s more, by supporting a limited franchise (that is to say the enfranchisement of women on the same terms as men), not universal adult suffrage, Hardie demonstrated hat he could be pragmatic and principled.

On the one hand, he judged that supporting a limited franchise had more chance of success than pushing for universal adult suffrage, which became the SDF’s position in 1907. On the other hand, it was a principled challenge to elements of the Labour movement who feared such a move would strengthen the middle class vote, and preferred to seek the franchise for all adult males.

Radical tactics

While Hardie may not have been particularly radical in backing a limited franchise, he was extremely radical in his support for the tactics adopted by the suffragettes. We should acknowledge just how militant and almost anarchistic these tactics were. Sylvia Pankhurst described them graphically in The suffrage movement: an intimate account of persons and ideals:

“Street lamps were broken, keyholes were stopped up with lead pellets … golf greens all over the country [were] scraped and burnt with acid… Old ladies applied for gun licences to terrify the authorities. Telegraph and telephone wires were severed with long-handled clippers; fuse boxes were blown up… There was a window-smashing raid in the West End, the Carlton, the Reform Club, and others were attacked.”

Hardie categorically defended these actions, proclaiming, “What else is left to them but militant tactics?” He even went on to claim that “the only fault to be found with the tactics is that they are not big enough, that they are too petty”.

Hardie by no means saw the acquisition of the vote as the end of women’s liberation. In From Serfdom to Socialism he expressed doubts about the extent to which women would fulfil their aspirations once the vote was won. The only way “the position of women would be revolutionised”, he said, was through socialism. His ultimate ambition was the creation of a society whereby women “in choosing a mate … will no longer be driven by hard economic necessity to accept the most accessible from a world point of view but be guided exclusively by an all-compelling love”.

But in other respects Hardie’s views were conservative. For instance, he saw motherhood as “the most sacred of all duties”, and he held a “deep conviction” that enfranchisement would render women “better mothers”.

He also held the conventional model of a married, monogamous family unit in high regard. For example, he was scathing in his criticism of Emily Lancaster and her partner for opting to live in a ‘free love union’ rather than marry, despite the couple explicitly arguing that marriage “destroyed women’s independence”. And when his ILP colleague Tom Mann attended meetings with a woman who was not his wife, Hardie forced him to resign as secretary of the ILP, although later he was involved in an extra-marital relationship himself with Sylvia Pankhurst.

Indeed, Hardie was criticised by Christine Collette (in History Workshop in 1987) who claimed that his paper, Labour Leader, offered “no protracted discussion of sexual politics”. She also accused the ILP of being indifferent to the issue of women’s participation in the Labour movement. Even Carolyn Stevens, who calls Hardie a feminist (in her 1987 PhD thesis A Suffragette and a Man: Sylvia Pankhurst’s personal and political relationship with Keir Hardie, 1892-1915), concedes that he occasionally adopted a “patronising tone” in his articles.

Nevertheless, Hardie agreed with John Stuart Mill’s conviction that “the principles which regulate the existing social relations between the two sexes – the complete legal subordination of one sex to the other – is wrong in itself, and now is one of the chief hindrances to human improvement”.

There were personal factors which shaped Hardie’s commitment to the cause of women’s liberation, namely his association with the Pankhurst family and close relationship with Sylvia Pankhurst, yet undoubtedly there was an ideological basis for his views too, and these existed before his involvement with the WSPU. Stevens even argues that it was Hardie’s column in the Labour Leader which influenced the Pankhurst sisters “to take up the cause of women’s rights themselves”.

Personal and class dimensions

However, Stevens also suggests that the absence of Hardie’s biological father played a considerable role in shaping his attitude to equality of the sexes. Hardie’s father was a middle-class doctor from Glasgow who had refused to marry his mother, causing her to “suffer greatly … in her reputation”.

Stevens claims Hardie’s pseudonymous ‘Lilly Bell’ column in the Labour Leader was a “barely disguised … lament of a loyal son for his mother’s honour … decrying the advantage that his biological father … had taken of his mother years before”. Although the exact details of his father’s background are disputed, for Stevens, the fact that Hardie was ‘illegitimate’ introduced a deeply personal aspect to his feminism.

This emerges, she says, through Hardie’s challenge to Victorian sexual repression and doublestandards, his claim that “there is too much prudery”. “To what depths of degradation has our humanity fallen, when the very means by which this humanity is perpetrated is regarded as unclean, and almost as if it were ‘of the devil’ instead ‘of God’,” he wrote.

This emerges, she says, through Hardie’s challenge to Victorian sexual repression and doublestandards, his claim that “there is too much prudery”. “To what depths of degradation has our humanity fallen, when the very means by which this humanity is perpetrated is regarded as unclean, and almost as if it were ‘of the devil’ instead ‘of God’,” he wrote.

There was also a class dimension to his feminism. He wrote about the need to “empower large masses of women” and emphasised the condition of “ordinary women” and “the plight of the poor”, while he also defended working class women involved in prostitution against discrimination by the state. He highlighted the fact that Lady Sybil Smith had been released after serving four days of a 14 day sentence, asking for such clemency to be extended to all suffragettes, not just those of high social status. And he argued for the minimum wage on the basis that it would offer support “especially to young working girls”.

He did hold some unconventional views, too, however. For instance, he argued that equality would steer Britain away from what he termed “race suicide”. “Were women freed from their … bondage, they would have a freer choice … in the selection of a father for their children and the tendency would then be for the less fit to get left, and the more fit taken,” he said.

He also indulged in occasional nostalgic romanticism about the role of women. “The old-fashioned type of woman is becoming scarce,” he wrote, the type who “never fussed, patching, darning, knitting or sewing, keeping the cradle gently rocking with a light touch as she crooned some old ballad… She ruled her little kingdom in love and gentle firmness.”

On the other hand, he argued that women “should and could do men’s work in most instances”, and in this respect he was ahead of his time. In fact, such was Hardie’s commitment to feminism that in 1907 he was prepared to quit the ILP and the fledgling Labour Party if they did not agree to support the campaign for limited female suffrage.

For Hardie, socialism and feminism were inseparable. The Labour movement, he said, had “to recognise the perfect right of every human to equal treatment because they are human beings”. Women could not be truly emancipated without the success of the Labour movement, but the Labour movement could not be credible unless it took up the cause of women’s emancipation.

Common ownership

There’s no doubt Hardie saw himself as a socialist. After all, he proclaimed when he first entered Parliament in 1893, “I am a socialist.” In 1901, he moved a motion in the House of Commons calling for a Socialist Commonwealth “founded upon the common ownership of land and capital, production for use not for profit, and equality of opportunity for every citizen”.

In From Serfdom to Socialism Hardie goes into some theoretical detail about the nature of his political philosophy. He was familiar with the work of Karl Marx, describing the Communist Manifesto as “the most fateful document in the history of the working class movement”. He also described the ILP as “an integral part of the movement … acting as the advanced guard, careful at all times … not to be out of touch with the main body of the army” because “that was what Marx intended the socialist section of the working class movement to be”.

Yet, Hardie did deviate from some aspects of orthodox Marxism believing “the transference of industries from private hands to the state” would be “a gradual and peaceful process”. And he challenged the notion that armed revolution was necessary, saying “with the enfranchisement of the masses, it is recognised that the ballot is much more effective than the barricade”.

Christianity also had a direct influence on Hardie’s political ideas. Indeed, he claimed that “the impetus which drove me first into the Labour movement, and the inspiration which has carried me on in it, has been derived more from the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth than from all other sources combined”.

When Hardie argued for a Socialist Commonwealth he said:

“We are called upon … to answer the question propounded in the Sermon on the Mount as to whether or not we will worship God or Mammon.”

However, he viewed the Christian movement in the context of the class struggle. For him, ‘Jesus the communist’ is part of a social history that includes the Peasants’ Revolt, the communist sect during the English civil war, Robert Owen and William Morris. He explicitly talks of ‘Jesus of Nazareth’ and ‘Jesus the communist’, rather than ‘Jesus Christ’.

It was not the divinity, but the politics of Jesus that mattered. For him, it was socialism, not Christianity, which offered “the one chance left of saving civilisation”. Hardie told a Methodist congregation that socialism was “a new religion much superior to Methodism or any other form of Christianity”.

He also held secularist convictions, writing:

“As religious belief is a personal concern, I am opposed to its enforcement or endowment by the state either in church or in school.”

However, he rejected some forms of radicalism and those aspects of the socialist movement which espoused what he saw as “dreamy utopianism”. Instead, he believed himself to be part of the “modern socialist movement”, whose “birth certificate was written in the form of the Communist Manifesto”.

He engaged with the discourse of his time, and grappled with concepts such as historical materialism, economic determinism, class war, the role of the working class party, and the ideological conflicts between utopian and scientific socialism. But he adopted a deliberate style, using simple language in order to express his ideas in a way that was “easily understandable by plain folk”. For Hardie, it was to the working class, or “the plain folk”, that the movement must look if it was to have any hope of bringing about socialism.

Ethical socialism

Many scholars have used the term ‘ethical socialism’ to define Hardie’s politics, although Hardie himself did not use the term. He did talk of himself as a ‘communist’, although the meaning of that term later altered significantly after the Russian revolution of 1917. Any broad term runs the risk of ignoring the complexities, distinct traits and contradictions in Hardie’s political perspective.

Ramsay MacDonald claimed that Robert Burns’ ‘The Twa Dogs’ and ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That’ were more important political texts for Hardie than Das Kapital. Yet Hardie was not politically unsophisticated. He clearly engaged with theoretical questions of Marxism and utopian socialism, read John Stuart Mill, Tom Paine and Thomas Carlyle, and was acquainted with Darwinism.

Ramsay MacDonald claimed that Robert Burns’ ‘The Twa Dogs’ and ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That’ were more important political texts for Hardie than Das Kapital. Yet Hardie was not politically unsophisticated. He clearly engaged with theoretical questions of Marxism and utopian socialism, read John Stuart Mill, Tom Paine and Thomas Carlyle, and was acquainted with Darwinism.

He did not just dream of an egalitarian future but was quite specific in how equality would be achieved, namely by the working class gaining control of the state. His feminist ideas displayed a depth which went beyond the acquisition of voting rights. And his internationalism operated on numerous levels – he sought not only co-operation between states, and self-determination for India and Ireland, but also unity across the working class. He was perceptive enough to realise that, despite his hopes that organised labour in Britain and Germany would oppose the war, “those who have motives in keeping up the agitation … (could) force one upon the two countries”.

Finally, despite championing causes such as anti-imperialism and republicanism, he was pragmatic enough to appreciate that electoral success would depend at least in part on gaining support from middle class electors and he urged the Labour movement to make “special efforts to reach them”.

At his death, however, it was as labour’s champion that Hardie was remembered, not least by the Irish republican and socialist leader, James Connolly, who wrote:

“By the death of James Keir Hardie, labour has lost one of its most fearless and incorruptible champions, and the world one of its highest minded and purest souls…

“He was a living proof of the truth of the idea that labour could furnish in its own ranks all that was needed to achieve its own emancipation, the proof that labour needed no heaven-sent saviour from the ranks of other classes. He had been denied the ordinary chances of education, he was sent to earn his living at the age of seven, he had to educate himself in the few hours he could snatch from work and sleep, he was blacklisted by the employers as soon as he gave vent to the voice of labour in his district, he had to face unemployment and starvation in his early manhood, and when he began to champion politically the rights of his class he found every journalist in these islands throwing mud at his character, and defaming his associates.

“Yet he rose through it all, and above it all, never faltered in the fight, never failed to stand up for truth and justice as he saw it, and as the world will yet see it.”

—-

This is an edited version of a talk given as part of Durham Branch WEA Study Group’s series ‘Politicians, Thinkers and Activists’ at the People’s Bookshop in Durham on Sunday 10 March 2013.

Paul Simpson has an MA in Modern History from Durham University. He was nominated for the 2009 History of Parliament Prize for his undergraduate dissertation at Queen’s University Belfast on ‘The Politics of James Keir Hardie’.

More ILP anniversary profiles can be found here.