Merely denouncing ‘One Nation Labour’ as more of the same is a political cul-de-sac, argues MATTHEW BROWN. We need to recognise some genuine attempts to rethink the left’s project and engage with the best of their ideas.

“Sooner or later any campaign or movement for change in society has to deal with the process of government, how collective decisions, whether national or local, are made and upheld.” So says the ILP’s statement, Our Politics, agreed little more than two years ago at the organisation’s Weekend School in May 2011.

It goes on: “Actions by national governments have a vital and potentially crucial role in addressing many of the problems we face, whether nationally or, by acting collectively, internationally.

“In Britain, that means we have to engage with the Labour Party… Any attempt to progress radical change will have to go through a social democratic agency.

“However, we have no illusions about the current political and organisational state of the party, about the corrosive effects of New Labour’s dominance over 16 years. Now is a time for the Labour Party to reflect upon its record in office, to see whether it can present a credible narrative for progressive change. It has a long distance to travel to win back public trust.”

Quite how big that gulf in trust has become was apparent at this year’s Weekend School less than two months ago when ILPers and friends had their first opportunity to “engage with” current Labour Party thinking as it’s beginning to emerge through the One Nation concept revealed by Labour leader Ed Miliband at his conference speech last September, and since referred to in many articles, speeches and comments by figures in and around the Labour leadership.

One of those key figures is Jon Cruddas, MP for Barking and Dagenham and coordinator of Miliband’s policy review process. The format agreed for the school was to use one of Cruddas’s speeches to kick off a discussion about the ideas behind the One Nation Labour label, to consider what, if any, philosophy it rests on, and what kind of political approaches and policies it may lead to.

The speech chosen was one Cruddas gave in February at the launch of a new project by the Institute of Public Policy Research, called ‘The Condition of Britain’. This was not intended to be representative of everything that’s been said about One Nation Labour or the policy review, nor even to epitomise the approach. Indeed, it was chosen partly because there was an accessible recording of the speech which would help provide a focus for thinking alongside the words on the page. Or so it was thought.

Cruddas has said and written a lot since Labour’s 2010 election defeat, not just about the policy review, but also about what he sees as the longer-term roots of Labour’s problems and, in particular, some of the ‘lost’ traditions of left-wing thinking that were once part of its make-up – around community, self-help, co-operation, local identity, and grassroots campaigning. Indeed, he has expressly spoken of the early ILP as embodying some of this “romantic” socialism, which he believes was subsequently buried under the more “rational” seam that later became embedded in Labour’s state-centred social democracy.

Among the growing range of other material available on the One Nation theme are various speeches and quotes by Miliband, articles by Labour thinkers such as Jonathan Rutherford, interviews with Maurice Glasman, and an e-book published by the Labour List website and edited by Cruddas himself.

It was hoped, even expected, that most of those attending the Weekend School would have been familiar with these significant developments in the Labour Party and so would bring with them some background knowledge and thoughts. In the event, the discussion focused closely (although not always accurately) on the particular speech which everyone had in front of them and, in retrospect, perhaps that’s not surprising.

What was surprising, however, was the tone of hostility and distrust that soon emerged in the following discussion, an outpouring of anger that seemed as much to do with pent-up frustration at the record of the New Labour government, and the direction it took the party, as anything to do with the current leadership or Miliband’s One Nation initiatives. Perhaps such bitterness towards Labour is one of the legacies of “the corrosive effects of New Labour’s dominance over 16 years”, and in that sense is understandable, if not particularly helpful.

Wider issues

Many of the specific criticisms expressed in that debate have been captured in a more measured way by John Halstead and Ernie Jacques in their pieces for this website, and many of the points they make are perfectly valid and well-argued.

However, there is still a need to address some of the wider issues which never had a chance to emerge in that session, deeper difficulties that Labour, – and any movement for social change – has to confront, ones that some of those behind the One Nation concept may, perhaps, at least be trying to grapple with.

Some of these problems the ILP has long been pointing out, not only to Labour leaderships but also to the left. We have always argued that, while it is vital to engage with a social democratic Labour Party, we cannot abandon “any hope of a changed world” and merely surrender “to the politics of the present and the next election”.

Some of these problems the ILP has long been pointing out, not only to Labour leaderships but also to the left. We have always argued that, while it is vital to engage with a social democratic Labour Party, we cannot abandon “any hope of a changed world” and merely surrender “to the politics of the present and the next election”.

On the other hand, we’ve always said it’s futile to follow some on the left and “promise a glorious dawn in some unimaginable future with no sense of how to get there”, other than demanding more radical leaders and policies as if people will automatically support them whatever the consequences.

What’s made us distinct from much of the left has been a clear-sighted recognition of the pitfalls to progress in a conservative world, those opposing forces that make such automatic support for left ideas unlikely. Therefore, we’ve been able to acknowledge the obstacles that confront even a mildly social democratic Labour Party in winning approval for progressive measures.

These difficulties are created not just by the present “dire economic circumstances”, which Ernie acknowledges, the “intractable problems” for any government operating in the post-crash world – of dealing with the deficit, managing cuts, handling a shrinking budget, and so on.

They are problems not just of the neoliberal economy, but of what Soundings founding editor Doreen Massey calls the neoliberal “commonsense”, the “ideological scaffolding” around free-market capitalism that’s become so normal, everyday and internalised that it not only moulds our understanding of society and the economy, but shapes how we imagine ourselves and characterise our social relationships.

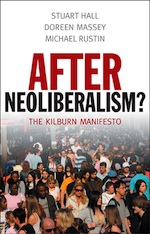

In her recent Soundings article, ‘Vocabularies of the Economy’, the first instalment of the so-called ‘Kilburn Manifesto: After Neoliberalism?’, Massey argues that “the vocabulary we use, to talk about the economy in particular, has been crucial to the establishment of neoliberal hegemony”. This vocabulary, “of customer, consumer, choice, markets and self interest moulds both our conception of ourselves and our understanding of and relationship to the world,” she writes.

“The new dominant ideology is inculcated through social practices, as well as through prevailing names and descriptions. The mandatory exercise of ‘free choice’ – of a GP, of a hospital to which to be referred, of schools for one’s children, of a form of treatment – is, whatever its particular value, also a lesson in social identity, affirming on each occasion that one is above all a consumer, functioning in a market.

“By such means we are enrolled, self-identification being just as strong as our material entanglement in debt, pensions, mortgages and the like. It is an internalisation of ‘the system’ that can potentially corrode our ability to imagine that things could be otherwise… Everything begins to be imagined in this way.”

Political work

However, Massey is careful to point out that this is cultural, and therefore political; that neoliberal commonsense is neither natural nor fixed, nor was it an inevitable result of the sweeping triumph of free-market economies over the last four decades. It took “political work” to establish – by the right and their cultural agencies in the media and elsewhere – and therefore it can be challenged and changed.

Massey’s aim, along with her Manifesto co-authors, Michael Rustin and Stuart Hall, is to begin the political work needed on the left to claw back some of the lost ideological ground. In their “framing statement”, published in May, they said: “Our purpose is to set out an agenda of ideas for a progressive political project which transcends the limitations of conventional thinking as to what it is ‘reasonable’ to propose to do. We will try to open a debate which goes beyond matters of electorable feasibility, or of what ‘the markets’ will tolerate.”

What is not clear from the material published so far (the manifesto is being revealed in five instalments over the coming months) is where, if anywhere, they see the Labour Party in relation to such a project, either in its current One Nation state, or as a potential vehicle for social change in the longer term.

What is not clear from the material published so far (the manifesto is being revealed in five instalments over the coming months) is where, if anywhere, they see the Labour Party in relation to such a project, either in its current One Nation state, or as a potential vehicle for social change in the longer term.

Indeed, they are – as so many of us are – critical of its timidity in opposition, saying: “It has been rendered speechless by the charge that it opened the door through which the Coalition is triumphantly marching. It seems unable to draw a clear line in the sand: a political frontier… to enunciate an alternative set of principles, to outline a strategic political approach, or to sketch out a compelling alternative vision.” How true.

However, they also acknowledge that: “Electoral change is urgent, critical and necessary”, adding that “it will not change much if it means a continuation of the existing assumptions under a different name”.

Perhaps One Nation Labour will be merely “a continuation of the existing assumptions”, “‘more of the same’ new Labour propaganda”, as Ernie puts it. After recent speeches by Miliband and Ed Balls on spending and welfare cuts, and by Stephen Twigg on education, there are doubtless many who have already decided that’s exactly what the One Nation ‘brand’ of Labour amounts to.

But, if you listen carefully, there is potentially some correspondence between what Cruddas and co are saying and the thinking of the Kilburn Manifesto crowd. In his IPPR talk, for example, Cruddas said, “we have introduced markets and financial transactions into areas of life they do not belong”, and talked of the need to move “beyond the old answers”, just as Hall, Rustin and Massey talk of the need to call “the neoliberal order itself” into question while also stating that “this is not a question of restoring the tried remedies of the post-war welfare state settlement”.

Both, it seems, are grasping after something new.

In fact, the connections between the two currents of thinking may be even closer. Cruddas and Rutherford (former Soundings editor, part of Miliband’s advisory team), cited ideas associated with the New Left – the tradition from which Hall, Rustin and Massey all come – in their 2010 paper on ‘Ethical Socialism’. And last summer a conference to explore “the New Left as a source for Labour’s ideological renewal” was held in London with Rutherford, Rustin, Cruddas and Glasman among the speakers.

Three of those conference papers have recently been published in the journal Renewal, whose guest editor, Madeleine Davis, wrote in her introduction: “Thinkers of ‘One Nation Labour’ are right to sense the enduring value of the New Left’s attempt to root a revitalised left project in contemporary English culture and society, and right to see in the democratic, humanist and communitarian emphases of the early New Left a valuable ‘road not taken’, worth renewed exploration.”

How far those “democratic, humanist and communitarian” values end up influencing Labour policy and direction remains to be seen. But it seems churlish to ignore the fact that some attempt is being made to “transcend the limitations of conventional thinking”, and to move “beyond the old answers”.

As Cruddas put it in his IPPR talk: “For 30 years British politics has been dominated by the market and the state. But we do not live by the managerialism of the state nor by the transactions of the market. We live in families and relationships and networks of friendships in local places.”

This could be merely “motherhood and apple pie”, as John calls it. Perhaps it is. But maybe we should take it at face value and accept that there are at least some around the current Labour leadership who are trying to think in new ways about some devilishly difficult problems.

That doesn’t mean we will necessarily like the answers they come up with (we rarely do), but ‘engaging’ might at least give us the chance to talk, even to be heard.

Finally, let’s go back to that quote from Our Politics at the start of this article. The sentence missed out, where there’s an ellipses in the second paragraph, is this: “While many on the left wish to avoid the Labour Party, to denounce or live outside it, we think this is a cul-de-sac.”

We still do.

—-

See also: ‘The Condition of Britain: A Response to Jon Cruddas’, by John Halstead, and ‘The Condition of Britain: The Debate Goes On’ by Ernie Jacques.

The speech by Jon Cruddas at the launch of the IPPR’s ‘The Condition of Britain’ project can be read here.

More about the Kilburn Manifesto is available here, including the framing statement, ‘After Neoliberalism: Analysing the Present’, and Doreen Massey’s ‘Vocabularies of the Economy’.

Some papers from the edition of Renewal on ‘The Labour Party and the New Left’ are available here.

A report of the ILP’s 2013 Weekend School is here.

Our Politics, the ILP’s political statement agreed in May 2011, is here.

17 January 2014

[…] Click here to read a series of articles on the ILP website discussing one nation Labour. Tags: Economics, Health, Policy, Public services, The Labour Party […]

26 September 2013

[…] Click here to read a series of articles on the ILP website discussing one nation Labour. Tags: One Nation Labour, Policy, The Labour Party […]

15 August 2013

[…] ‘The Need for Engagement’, by Matthew Brown […]

16 July 2013

Jonathan : From the ILP’s published perspective “The Labour Tradition and the Politics of Paradox” is by no means as unproblematic as you seem to think it is. Towards the end of Maurice Glasman’s article, he concludes by pressing for four commitments. These are (1) to local, relational or mutual banking, (2) to skilled labour, to real traditions of skill and knowledge, (3) to the balance of power within the firm and (4) to forms of mutual and co-operative ownership. I am all for seeking to influence Glasman on what these would mean as Labour Party policy proposals. It is when he goes on to say that “Socialism is a condition of sustainable capitalism” that I start to worry about what he is trying to sell to you, me and the ILP. I thought that we believed that socialism meant rather more than this.

In 1956 a group called Socialist Union produced a book called “Twentieth Century Socialism” in which they claimed that “a Socialist economy is a mixed economy, part private, part public, and mixed in all its aspects”.

Whilst I believed (and still believe) that Socialist Union’s position was wrong in the mid 1950s, I would now be quite happy (for a period) to see a Labour commitment to seek to re-establish a form of mixed economy – which would be a modern-day varient of what Socialist Union had in mind. For today, it could give us space to eventually move in a more fully-fledged socialist direction. We missed this opportunity in the 1950s up to the 1970s. Then Thatcherism built on our failures. Hence our current difficulties.

In this debate (but on a different thread) I have argued the if New Labour was a form of Thatcherism, then One Nation Labour can be seen as a form of pre-Thatcherite Conservatism. I actually see that as an improvement, but I don’t wish us to be fooled into thinking it is a form of socialism. Nor is the One Nation approach the sole property of Ed Milband. Ferdinand Mount (a former head of Margaret Thatcher’s policy unit) has peddled something similar – recently in “The New Few or A Very British Oligarchy”. Jon Cruddas commends it saying “Brilliant….Demands respect and has to be read”. So perhaps he shares Mount’s wavelength.

I am for engaging with the One Nation Labour debate, but feel that we need to try to make an impact to get it (a) to clarify what it is saying, (b) to jettison what might be counter-productive and (c) advance what is feasible. We don’t have to look into the crystal ball for Labour’s One Nation case. Every Labour Party member has received a booklet entitled “One Nation Labour”, which lists nine of Labour’s policy commitments. It came with our European Candidate’s Ballot Paper. If this is the rebanding of Blue Labour for a wider audience, then what are its strengths and weaknesses? And how should the ILP respond to it?

Basically (spread over the five threads of this current ILP debate) we seem to have people dug (more or less) into two separate camps, as expressed by Barry Winter and Graham Wildridge. But perhaps there is a socialist third way.

13 July 2013

I’d like to thank Barry for addressing the question I asked at the very beginning of this thread.

Before denouncing ‘One Nation Labour’, it is worth reading ‘Labour and the Politics of Paradox’. For all its faults, ONL – which is clearly a rebranding of ‘Blue Labour’ for a wider audience – is a reaction against the relentless post-modernist globalising tendencies of Blairism. That is something I have sympathy for.

Unfortunately, as is the way of things, Blue Labour’s social policy aspirations have been subsumed by some very conventional economic thinking. This brings me back to my original questions: how do we engage, what do we say and what do we want to achieve in concrete terms (i.e. what policies do we want to influence)?

Unless we are able to address these questions, and make some persuasive points about economic policy, we can engage all we like, but few will listen.

That still allows us to refine our perspective by thinking creatively and openly about what ONL could mean, but, to me, that seems like an academic exercise, albeit it an interesting one, with some intrinsic merit, rather than a political project.

12 July 2013

Rather reluctantly, I feel it necessary to respond Graham’s comments. For me, Matthew’s account offers a thoughtful and measured consideration of Labour’s policy review and how we might constructively engage with it. Graham appears to want none of that. He prefers to accentuate the negative. Keeps it simple, I suppose.

A lot depends on what we mean by ‘engage’ in this context. I’m inclined to see it as helping us to clarify the ILP’s perspectives on the matter. If we manage to do that, then we might be able to engage with those who are developing the ideas. However, at this stage, I’m less interested in that than winning a wider hearing for what we are trying to say. Not that the two approaches are mutually exclusive.

The key thing, I’d suggest, is to acknowledge the enormity of the challenge facing the Labour Party. As Maurice Glasman argues, the rupture of trust between the party and its traditional supporters – who are far from being on the left – is enormous. Yes, we can point the finger at New Labour’s failings here. Yes, we will often be disappointed with what emerges. But can we be part of a process that pushes the party in a more progressive direction?

Add to that, we have to recognise the party’s parlous internal condition (true of all mainstream parties but that does nothing to diminish Labour’s problem). The recent spat over Falkirk is but one of the symptoms.

For these and other reasons, keeping it simple is not so much a political option but is simply opting out.

Sadly, I have to say that Graham’s unduly pugnacious prose does neither him nor his argument any favours. I realise that this is often what passes for debate online but fear it’s more likely to diminish, rather than help, genuine dialogue. On occasions, in the pub maybe, it may serve a purpose. More often than not, however, it simply encourages people to trade abuse. Let’s try not to go there.

6 July 2013

Matthew Brown is WRONG when he says there is an either/or conflict between ‘the need for engagement’ versus ‘denouncing (Matthew’s word, not mine) One Nation Labour’.

Am I excluded from engagement just because I want to say that there are aspects of ‘One Nation Labour’ that I should like to be debated more?

Let’s give a few examples. Nation, country and family are words tainted by 20th century history that no socialist can easily adopt. And in the torrent of ‘One Nation Labour’ essays that Matthew documents there is no internationalism, silence on Labour’s foreign policy errors, dithering on European Union relations.

However, my main point is where and how is this engagement supposed to happen?

I didn’t choose the particular Cruddas speech to frame the discussion at the ILP Weekend School, therefore I cannot be blamed for exposing Matthew’s delusion about engagement. It was contained in Cruddas’s opening words: “My job is to organise the Policy Review of the Labour Party. We have set up three Shadow Cabinet sub-committees chaired by Ed Miliband on: the economy, society and politics.”

You will notice that there is not even a nod in the direction of the Labour Party’s deeply flawed Policy Forum. Indeed, Cruddas couldn’t be bothered to reference Angela Eagle’s ‘Your Britain’ discussion website (which goes nowhere). And if you read the NEC reports from Ann Black and Johanna Baxter you will see that they record that Cruddas doesn’t turn up at either the NEC or the Joint Policy Committee.

Engagement? Really? In what way were any Labour Party members consulted when Ed Miliband and Ed Balls made their June 2013 game-changing declarations on welfare payments and government budgets?

The general view is that Labour’s slogan for the 2015 election is: “Vote for us and get a Tory government.”

Why would the ILP want to be involved in that disaster?

2 July 2013

My perfuse apology Matthew. Getting your name mixed up with Will was a bit of a boo-boo. I can only plead age and lack of focus and as you rightly say, a tendency to prejudge and to jump-in feet first.

But, having said that, I promise you I did read your article and liked (quite a lot) of what you had to say about the ILP perspective, the need to win friends and the balance you have given to the debate.

2 July 2013

The trouble is, when someone can’t get the name of the author right (it is written in capitals at the beginning), I’m tempted to think they haven’t read the piece all that closely.

While mistaking me for Will is trivial, even amusing (in some ways), it does betray a degree of assumption, of pre-judgement, of someone reacting on the basis of expectations rather than what’s written. It seems to me, this is how some people reacted to Cruddas’s talk.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think I’m any less cynical or angry than Ernie is. Ernie expresses his anger at what the Tories are doing, and Labour’s limp response, very well. I disagree with little of it.

But, while “anger can be power”, as The Clash once sang, on its own it doesn’t help us navigate a way through the problems posed by the dire situation the left is in.

While the ILP has never flinched from being critical of Labour when it’s necessary (and it often is), we have always recognised the severe constraints under which it operates in a hostile culture and tried to suggest possible ways to overcome them that neither leave it utterly unelectable, nor allow it to take its eye off the goal of longer-term and more radical social change.

We argue that Labour cannot do this through electoral politics alone, nor can it do it on its own – that it needs a political movement and culture around it to sustain and influence it. What’s interesting about some of those around the current Labour leadership, such as Cruddas, is that there are signs they appear to recognise this, that at some level they may understand the need to build an alternative political culture as well as an electable party. There’s something of that in the notion of ‘One Nation’. I say “something”. It’s very uncertain.

Anger – though sometimes useful – is easy. I do it often. This is incredibly difficult.

2 July 2013

Unsurprisingly, I do agree with most of what William [sic] has to say in this article which is thoughtful, intellectually thorough and does something that we, the more cynical and disbelieving ILPers, miss out or simply forget, namely, how the message presented by Jon Cruddas and the One Nation Labourites fits with the ILP perspective.

In particular, how do we reach out and engage with those in the Labour leadership, Labour Party members, academic thinkers, trade unions, community activists, and beyond, who might be sympathetic to ILP policy and who really do want to move in the direction of a more humane, egalitarian, democratic cooperative and inclusive society and system of government.

Sadly, as we all know, we are a lonely and quite insignificant voice trying to make ourselves heard in a society that seems to be going backwards, where greed, selfishness, individualism, scamming, thieving and beggar-thy-neighbour behaviour and politics seems to be the order of the day.

‘Look after number one’ has never been a more appropriate label and philosophy underpinning the aims of the present government and of large swathes of British society including many young people.

When I listen to William [sic!] and read what he has to say I must admit to being a bit schizophrenic insofar as he has a real knack of making me feel less certain about what I say and do, and very uneasy about the contradictions that I know we all internalise, to a greater or lesser extent.

But being aware of all this, I still find it difficult to suppress the anger and frustrations that overwhelm me when the Labour Leadership virtually accepts the Con/Dem austerity agenda (as though there were no other possible options) and promise more of the same if elected in 2015.

For instance, in his recent spending review, George Osborne had another pop at the welfare state and the unemployed but there was hardly a whimper from the two Eds (Balls, Milliband) and the Labour Party about the likely effect of these nasty, vindictive and economically nonsensical proposals.

His announcement that sacked workers will have to wait seven days before getting benefits is another sickening attack on unemployed people who are paying a heavy price for an economic crisis they had no part in making. To my mind, this shows a complete lack of concern or understanding of working people who pay their National Insurance in anticipation that when they lose their jobs there is a basic safety net (and Jobseekers’ Allowance is certainly basic) to tide them over while they compete against each other for these lovely private sector jobs, via private sector agencies offering the minimum wage and a mix of part-time, temporary and zero-hour contracts.

No wonder they can brag about creating a million jobs while keeping quiet about the hundreds of thousands public sector jobs lost and the avalanche of UK jobs that continue to be outsourced, day-in, day-out.

It simply doesn’t seem to bother most of the political class (and certainly not this government) that being sacked in such circumstances is not only traumatic for all the individuals concerned, and their families, but that many thousands of these unfortunate jobseekers will be forced into the hands of pay-day lenders (some of whom fund the Conservative Party) and loan sharks, and that a growing percentage of unemployed people will then find themselves joining the queues for food banks which now help to feed over half a million UK citizens. This is a process which started and continued unchecked under New Labour.

The sad thing about this austerity strategy is that, despite Miliband’s One Nation rhetoric, the Labour Party seems collectively to act like a terrified rabbit frozen in the lights of the fast approaching car that is going to dispatch it into the afterlife, not knowing what the hell to do. This seems to be a strategy which amounts to doing and saying nothing in the hope of getting back into office by the back door so that they can manage the nation’s affairs and progress their careers in a way that’s not too dis-similar to the Con/Dem government.

But this is where I get schizophrenic again, knowing in my heart of hearts that Will [sic!!] is right (back to the ILP perspective again). We never had any illusions about the current Labour Party, or about being in it for the long haul. But it has been a bloody long haul insofar as we (the ILP not Will [sic!!!] and me) have been at it for 120 years now.

But there again, when we (there is just a chance I might not be around then) do reach the promised land, it should be well worth the wait.

2 July 2013

I’m not sure what ‘Will’ thinks, but as the writer of this piece (it pretty clearly says ‘MATTHEW’ at the beginning!), I think the easiest way of answering your question is to turn it around. Why would you not want to engage with Labour? To what end? What would your alternative be?

I don’t want us to engage with Miliband himself so much as some of the ideas that are shaping Labour’s thinking, rather than just viewing them through a lens of distrust shaped by the legacy of new Labour. As I say in the article, that doesn’t mean we’ll agree with all those ideas, necessarily, or like the policies they lead to – and when we don’t , we say so, as we always have. But taking their ideas seriously – rather than reacting in a knee-kerk way – might, at least, give us a chance to reach other people who are interested in them and offer our own perspective. We might learn something too.

And, as it happens, I do think it would make a difference if Labour started to challenge the vocabulary that shapes so much of mainstream discussion of our political economy. The words that are used are no accident, they carry with them all kinds of assumptions and prejudices. Accepting those assumptions means Labour is always operating on the right’s terms, literally.

1 July 2013

In embracing ‘Blue Labour’, I think Ed Miliband is taking a very different path from New Labour, acknowledging the importance of stability in people’s lives and resisting change when it is bad for communities. The prominence of the Living Wage campaign in Labour’s publicity both nationally and locally is one of the fruits of this change.

He faces huge challenges – not least how to rebuild an economy which is still bedevilled with private debt, and which is dysfunctionally focussed on the City of London, the source of many ills, but also of a great deal of international investment. Thirty years of neo-liberalism has left business struggling and weak throughout rest of the country.

So, I suppose he could do with all the help he can get. The problem is I don’t know why Will wants to engage with him, to what end? Is it so Miliband starts using a different vocabulary or for some more substantive policy changes? If so, what changes are we talking about?