HAZEL KENT traces the life and career of Fenner Brockway, with particular emphasis on his long association with the ILP.

Although I never had the pleasure of meeting Fenner Brockway, I spent three fascinating years in his company while researching his contribution to the ILP for my PhD thesis. Study of his books, newspaper articles, minutes of committee meetings, annual conference reports, memos and letters confirm his importance to the history of the ILP.

During his ILP membership – from 1907 to 1946 – he held a remarkably varied range of roles: editor of the Labour Leader and later the New Leader; organising secretary; general secretary; political secretary; chairman; member of the Parliamentary group; and member of the National Administrative Council (NAC).

During his ILP membership – from 1907 to 1946 – he held a remarkably varied range of roles: editor of the Labour Leader and later the New Leader; organising secretary; general secretary; political secretary; chairman; member of the Parliamentary group; and member of the National Administrative Council (NAC).

Consequently, Brockway was at the centre of party decision making, although he was never really a leader. Rather he was a consummate committee man, planner, policy-maker, facilitator, organiser, writer, editor and propagandist. He wrote more of the party’s pamphlets and newspaper articles in the period 1922-1946 than any other individual and published 13 books during this period.

These writings, particularly his first autobiography, Inside the Left (1942), have been extensively utilised by historians of the ILP. This article seeks to provide an overview of his contribution to the ILP.

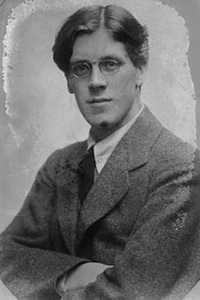

Archibald Fenner Brockway (1888-1988) was born in Calcutta, the child of nonconformist missionary parents. He was sent to England at the age of five, and educated at a school for the sons of missionaries in Blackheath. On leaving school at 17 he began a career in journalism, lodging in London with friends who shared his growing interest in politics. Brockway joined the Finsbury branch of the ILP in 1907, and so began an organisational allegiance which held the central place in his life until 1946.

Brockway believed unequivocally that socialism would provide humanity with a better future, and during this period he was convinced that the ILP was the organisational vehicle which could deliver that goal in Britain. He viewed socialism holistically, as a way of life which would transform human relationships on all levels. His views were based around core principles of equality, democracy and freedom. As a consequence, Brockway abhorred war and imperialism, and so his socialism was naturally both anti-imperialist and pacifist.

Brockway was a prominent conscientious objector in the First World War, establishing the No-Conscription Fellowship in 1914 and subsequently undergoing three courts-marital and sentences totalling 28 months’ imprisonment, including eight months in solitary confinement. This early experience, and his later associations with campaigns for peace and colonial freedom, tends to mean Brockway has been judged in relation to single issues, rather than the holistic nature of his socialist cause.

In 1977 he dismissed an assessment of him as the most successful politician of his generation, which suggested that he had seen the realisation of his life’s work through the dismantling of the British empire. “The tribute is generous, but it misunderstands: colonial liberation has been only a small part of my purpose,” he said.

His work for the ILP provides an opportunity to see how he put his views on socialism into political practice.

Brockway’s journalism

Brockway began his rise to national prominence in the ILP through his journalistic work on the Labour Leader. In 1910 he was offered the post of sub-editor, and this was followed by a promotion to acting-editor a year later. This put him into regular contact with leaders of the labour movement, such as Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden.

His rapid rise continued when he became ‘responsible editor’ at the age of 24. The editorship gave him a national platform and profile, allowing him to become a leading figure in the opposition to conscription in the First World War. Ironically, he was forced to resign in 1916 because, as an editor, he was exempted from conscription and Brockway felt that as a leader of the No-Conscription Fellowship he should “go through it on the same basis as the other members”.

He was very proud of his early career as editor of the Labour Leader. It connected him to the pre-First World War labour movement and added gravitas to his political persona despite his age and youthful appearance.

Brockway was intensely disappointed when he was not asked to return to his editorial position after the war. Historian FM Leventhal has suggested that this was because Brockway’s work had been ‘mediocre’. He did accept the offer of a part-time post of London correspondent, but felt alienated by this rejection and until 1922 tended to concentrate on other causes.

In 1920 he briefly became editor of India, as a result of his connection with British Committee of the Indian National Congress. In addition he worked on the Prison System Enquiry with Stephen Hobhouse and became chairman of the British No More War Movement and of the War Resisters’ International (WRI).

In 1922 Brockway once again became involved at the centre of ILP affairs. Clifford Allen, another prominent conscientious objector of the First World War, became treasurer, and their connection secured Brockway the newly created position of organising secretary.

He took charge of publicity and education, including the supply of literature. He was also responsible for assisting communication between the ILP at local and national level and generally acting as a co-ordinator between the varying sections. Brockway toured the country most weekends, addressing branches, divisional conferences and other demonstrations.

Brockway had not initially applied for the post, perhaps hoping for a parliamentary seat or a return to the editorship. Despite this, the energy and enthusiasm with which he undertook that position helped to advance the ILP, which made big gains at this time. This helped to establish Brockway as a vital figure in the party, and in 1923 he was propelled into the more senior position of general secretary.

In this role his duties included running Head Office, servicing NAC and parliamentary group meetings, and organising relations with the divisions. Brockway managed to transform the post of general secretary from an administrative one into an unprecedented position of substantial political influence, a remarkable achievement for a figure with no local powerbase or elected mandate. Comprehensive membership of diverse committees ensured his involvement in the creation of ILP policy.

The journey leftwards

Brockway’s knowledge of ILP affairs, gathered from the centre of his organisational web, was unparalleled and permeated throughout the party: divisions, branches, NAC, rank and file, MPs and conference delegates. He enhanced his position by representing the ILP and NAC in the wider labour movement, and he built a strong international reputation through his involvement with the Labour and Socialist International.

Despite his successes, however, Brockway was frustrated by the limitations of being a paid official. By 1926, as the political climate began to change within the party, he began to manoeuvre himself into a variety of different positions.

Despite Brockway’s personal association with Clifford Allen, politically he moved away from Allen’s intellectual, gradualist conception of socialist politics. Increasingly he became associated with James Maxton and the Clydeside group, and from the mid-1920s he began a political partnership and journey leftwards which were to characterise the rest of his time with the ILP.

Internal party squabbles, the failure of the first Labour Government and the experience of the general strike (during which Brockway had edited the northern edition of the British Worker) all contributed to Brockway’s growing impatience to see socialism established.

At first glance, Brockway appears to have had little in common with the Clydeside group, but he transferred his allegiance smoothly, while his broader perspective and knowledge of international socialism meant his contribution was useful to them.

When Maxton took control of the ILP in 1926, Brockway moved to the new position of political secretary. Most of his time in this position was taken up with the growing difficulties between the ILP and the Labour Party, although he continued his international work and, importantly, returned to another position within the party, as editor of the New Leader.

Brockway must have been delighted to be finally restored to the editorship. During Allen’s years the New Leader had been edited by HN Brailsford and was regarded as a great success. However, with the change in leadership, it was decided that the paper needed to be less intellectual and more focused on the needs of the rank and file party members, in Brockway’s words: “a paper not so much for the armchair as for the factory and the street”.

For Brockway, the New Leader was an important propaganda tool through which he could further the cause of socialism. In total, he edited the paper for 18 years (from 1926 to 1929, and from 1931 to 1946), writing the weekly editorials and many of the articles. Although readership steadily declined over the years, selling the New Leader consistently provided a positive focus for branch activity and it provided a way of communicating the ILP’s message beyond the party itself. Although an important element of his work, the New Leader was never Brockway’s sole focus, and he also applied his considerable energies to several parliamentary campaigns.

Beginning in Lancaster in 1922, Brockway fought a total of seven elections for the ILP. Lack of local connections with a particular constituency meant that he repeatedly had to start again, failing to build up personal loyalties and local ties, in marked contrast to his Clydesider colleagues. Most notable among Brockway’s contests was the 1924 Westminster by-election when he stood in a four-sided contest which included Winston Churchill – despite their enthusiastic campaigning, neither was successful.

In early contests Brockway’s popularity suffered because of his wartime conscientious objection, although he produced reasonable results, given the conservative nature of the constituencies.

Brockway was elected MP for East Leyton in 1929 and consequently became a member of the ill-fated second Labour government, and he was also chairman of the ILP parliamentary group in 1931.

As an MP he particularly focused on influencing government policy on India, but he became frustrated by lack of progress and failure to respond to events, such as Gandhi’s peaceful, civil disobedience campaign on the salt tax and the British authorities’ brutal response. This culminated in Brockway’s dramatic suspension from the House when he disobeyed the Speaker, insisting on parliamentary time being given to discussion of the deteriorating situation.

As one of the 14 rebel ILP MPs he regularly challenged the government, voting against them on unemployment legislation and on budgetary matters. The actions of the rebel group led to a serious crisis in the relations between the ILP and the Labour Party over the issue of parliamentary standing orders, which the rebel ILP group were not prepared to accept.

East Leyton was not a safe Labour seat, and Brockway was doomed to defeat in a two-sided contest in 1931, despite his energetic efforts as an MP. The financial crisis of 1931 led him to believe that capitalism was collapsing and drastically altered how he envisaged socialism coming about. He no longer thought change could come through a parliamentary route. When these circumstances were added to the bitter dispute between the ILP and the Labour Party, they produced a turning point in Brockway’s politics as he began to develop a revolutionary socialist policy.

The ‘disastrous error’

This was to have a significant effect on the history of the ILP, because, in April 1931, he was elected chairman of the ILP, a position he held until January 1934. Maxton was suffering one of his bouts of serious illness, and consequently had decided to step down from the official position of leader for a time, although he still remained a dominant influence. On becoming chairman, Brockway wrote:

“I find it difficult to express the feelings I have on becoming chairman of the ILP. If I were to say I am grateful for the honour which the members have done me, it would be far too formal and a little unreal… I would rather have the trust of the members of the ILP than any body of men and women in the world… I will do my best to justify their confidence.”

As chairman, Brockway presided over the most difficult and turbulent period in the ILP’s history: disaffiliation from the Labour Party. He took the role of chief negotiator with the Labour Party, and although outwardly the crisis was about parliamentary standing orders, for Brockway the real issue of significance was the development of a revolutionary policy. Negotiations were lengthy and complex, and the ILP was irrevocably damaged by the experience.

Eventually, by a vote of 241 to 142, a special conference took the decision to leave the Labour Party. Speaking to the conference, Brockway was enthused: “the ILP takes up its new task with full confidence… [it] will line up the whole working-class movement behind the red banner of revolutionary Socialism.” In contrast, 45 years later, he admitted: “My support of disaffiliation was the greatest political mistake of my life… [it was a] stupid and disastrous error.”

Having made the decision to disaffiliate, Brockway and those remaining in the ILP turned towards the creation of a revolutionary policy. Unfortunately, his rather vague ideas on workers’ councils did not provide the party with a clear position. The 1930s saw him become deeply embroiled in unproductive sectarian squabbling on the far left of British politics, particularly with the Communist Party of Great Britain, as the ILP’s political importance and membership waned. In addition, he devoted considerable time to involvement with the International Bureau for Revolutionary Socialist Parties, and created a network of contacts throughout Europe.

Brockway visited Spain during the civil war and helped organise the ILP contingent, a significant departure from his earlier pacifist views. He had decided that wars where socialists were fighting for socialism was very different to ones where workers were required to fight for capitalist governments. However, his frequent criticism of the Soviet Union’s purges and show trials in the pages of the New Leader during the mid-1930s demonstrates that, for Brockway, a revolution was only worth pursuing if it resulted in the establishment of democratic socialism.

Inside the ILP, Brockway returned to the post of general secretary in 1934 and continued to edit the New Leader. Maxton had returned to the chairmanship, and they worked as a team alongside the other NAC members. There were two notable exceptions, however, when they clashed over the ILP’s response to international events: the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935 and the Munich Agreement of 1938. On both occasions Brockway’s viewpoint was based on his more international outlook, while Maxton was more rooted in domestic concerns. Twice, Brockway had to back down, acknowledging Maxton’s pre-eminence in the party.

However, these squabbles were less important than their realisation that the ILP itself was experiencing terminal difficulties. Membership had plummeted and political influence seriously declined. By 1939 a special conference had been arranged to vote on reaffliation to the Labour Party, a course of action which Brockway had supported since 1937. The outbreak of the Second World War caused the conference to be postponed, and organisational isolation, coupled with his revolutionary response to the conflict, meant that Brockway spent the war on the political periphery.

Brockway initially responded to the Second World War by calling for revolution. He argued that as the imperialist British and fascist German governments were both capitalist states, workers should rise and establish socialism. The ILP stuck to this line throughout the war and Brockway used the pages of the New Leader to present the arguments. He fought two by-elections (Lancaster in 1941 and Cardiff in 1942), as the ILP refused to recognise the electoral truce or support the National Government. He continued to maintain his contacts with international socialists, despite the organisational difficulties.

Arguably, Brockway’s most important work during the war was outside the ILP, as Chair of the Central Board of Conscientious Objectors (CBCO). His activities were extensive and he took a close interest in the cases of individual conscientious objectors. He was particularly pleased that he was able to convince the authorities to recognise political reasons for objection.

‘The member for Africa’

By the end of the war, Brockway was certain there was a mainstream move towards socialism and he became excited by the ‘dynamism for change’ within the Labour Party. He did not stand in the 1945 General Election, as the ILP had decided not to oppose Labour candidates. Brockway continued uneasily in the ILP until 1946. When the ILP conference decided to remain completely independent from Labour, it was clear to Brockway that his long association had run its course. He resigned from his official posts, but retained his membership until after Maxton’s death in July 1946. Brockway applied to join the Labour Party in January 1947.

From 1950 his career entered another vigorous phase, with his election to parliament as Labour MP for Eton and Slough. He made a name for himself as the leader of the anti-colonial movement in Britain and was nicknamed ‘the member for Africa’, visiting that continent regularly and developing friendships with nationalist leaders. He became chair of the Movement for Colonial Freedom in 1954, and campaigned relentlessly for the introduction of anti-discrimination legislation in Britain.

He lost his parliamentary seat in 1964, in part because of the race issue. He was involved in founding the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), and in various campaigns for human rights: against apartheid in South Africa, and for Catholic civil rights in Northern Ireland. He initiated the ‘War on Want’ council to raise money for development, welfare and refugee relief, and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1961.

In 1964, he reluctantly agreed to enter the House of Lords as a life peer and continued to actively campaign for socialism into his late nineties. He was known for asking more questions than any other peer, although in later years hearing loss curtailed his ability to participate. He co-founded the World Disarmament Campaign with Philip Noel-Baker in 1979 and continued to campaign and travel abroad for this cause until the mid-1980s.

At the end of his life, he decided to rid himself of all his property – his house, library and papers – and he gave all he earned above the average wage in Britain to the peace movement.

Fenner Brockway died peacefully in hospital on 28 April 1988 with his two youngest daughters at his side and a smile on his face. He had lived an extraordinary life, devoted to the cause he loved: socialism.

—-

Dr Hazel Kent is a Learning Development Tutor at Bishop Grosseteste University in Lincoln.

Further reading:

Fenner Brockway, Inside the Left: Thirty Years of Platform, Press, Prison and Parliament (London, 1942)

Fenner Brockway, Towards Tomorrow (London, 1977)

Kent, H. (2010) ‘A paper not so much for the armchair but for the factory and the street’: Fenner Brockway and the Independent Labour Party’s New Leader, 1922-1946. Labour History Review. 75 (2). 208-26.

Nicholson, H. (2007) ‘Towards Socialism: Fenner Brockway’s political work for the Independent Labour Party, 1922-1946’. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Sheffield.