The death of Nelson Mandela in South Africa has rightly and understandably led to a flood of tributes and reflections from public figures all over the world. US president Barack Obama called him “a man for all ages” while Labour leader Ed Miliband described him as “the inspirational figure of our age”.

British prime minister David Cameron was among those who visited the South African embassy on Friday morning to sign a book of condolence, while the anti-racist organisation HOPE not hate has opened an online book of remembrance so all of us can make our own tributes and offer our own reflections.

British prime minister David Cameron was among those who visited the South African embassy on Friday morning to sign a book of condolence, while the anti-racist organisation HOPE not hate has opened an online book of remembrance so all of us can make our own tributes and offer our own reflections.

“We all know what Nelson Mandela did and the dignity and humanity with which he did it, but for each of us there will be something special we will remember him by,” explained the organisation’s Nick Lowles.

“He was a man like no other. His journey of defiance in the face of injustice defined the story of apartheid in South Africa. Yet it was his ability to forgive his opponents, and promote peace, which led his nation to democracy and inspired people across the world in their own struggles against racism and inequality.

“Words like ‘great’ and ‘hero’ are bounded around all too frequently, but for Mandela he was these and much more. To mark his sad death, we are opening a book of condolence to give you the opportunity to make your own fitting tribute.”

The online book – at http://action.hopenothate.org.uk/mandela-tribute – will be open for five days after which it will be delivered to the South African Embassy.

“We want it to be an opportunity for the HOPE not hate family to pay their respects and to reflect positively on his impact on our own lives,” said Lowles.

“We will mourn the passing of the greatest and most inspirational man of our generation but at the same time we are determined to celebrate his contribution by continuing to build a movement which honours his vision of equality, tolerance and reconciliation.”

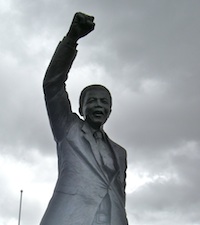

Mandela’s contribution to the end of apartheid and the birth of democracy in South Africa has inevitably made him into a symbol of peace and reconciliation across the world. But we should remember that the changes in South Africa were not one man’s work alone, they were the result of long, hard struggle – political struggle – by millions of people. And, at times, it was far from peaceful – thousands of people died fighting the apartheid regime.

The left in Britain, and elsewhere, including the ILP, played an honourable role in that struggle, supporting the ANC and other organisations through dogged campaigning and solidarity, leading the calls for boycotts, and keeping the plight of Mandela and other political prisoners in the public eye when many on the right, notably Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher, branded him a “terrorist”.

When the ANC called for sanctions against South Africa it wasn’t automatically heeded by the politicians – indeed, those on the right resisted for as long as they could. The fight to impose a boycott on the apartheid regime wasn’t won only around the negotiating table, but on cold pavements outside Barclays banks on hundreds of high streets, on the desolate forecourts of Shell garages, and outside the unwelcoming doors of supermarkets selling Cape fruit.

When the ANC called for sanctions against South Africa it wasn’t automatically heeded by the politicians – indeed, those on the right resisted for as long as they could. The fight to impose a boycott on the apartheid regime wasn’t won only around the negotiating table, but on cold pavements outside Barclays banks on hundreds of high streets, on the desolate forecourts of Shell garages, and outside the unwelcoming doors of supermarkets selling Cape fruit.

Many ILPers were part of those campaigns, along with others on the centre left, active in local anti-apartheid groups in places such as Durham, Leeds, Glasgow and London.

And it wasn’t only Thatcher’s government these campaigners had to confront, but the prejudices of the wider public – local publicans who refused to let their rooms for meetings with ANC speakers, for example, or local councils (including Labour authorities) who had to be persuaded to allow anti-apartheid marchers to use their town halls and city squares to celebrate Mandela’s 70th birthday.

Sometimes it’s hard to believe now, but in those days in the 1970s and ’80s the end of apartheid seemed like a far distant hope rather than an achievable goal. A bit like the Cold War and the Berlin Wall, apartheid felt immoveable – but we struggled to move it, nevertheless.

Mandela became a symbol of that struggle while he was still in prison, a figurehead around which the movement could galvanise and build broader support. When he was released his role in negotiating an end to apartheid made him a symbol of something else – of tolerance and forgiveness – and that, of course, is what many are now remembering in the wake of his death.

Yet, as Ed Miliband wrote today: “As we remember Nelson Mandela we also remember the hundreds of thousands of people in Britain who supported the movement he represented. Their efforts meant that Mandela described our country as the ‘second headquarters of the African National Congress in exile’.

“Together with millions of others across the world, these brave people demonstrated that even the mightiest obstacles can be overcome in the cause of justice.”

But the political struggle didn’t end with the demise of apartheid. Indeed, South Africa’s current problems, and its many mistakes since Mandela left office, prove what many on the left always said, that formal democracy alone could not bring about the promise of the ANC’s Freedom Charter for true equality and social justice. For South Africa, as for so many other nations, the dominance of neoliberal capitalism, and the power of global corporations, has made that task even harder.

Perhaps, then, the greatest tribute to Mandela would be for us all to engage in an honest evaluation of South Africa’s period of transition, an assessment of what’s gone wrong, and a renewed determination to fulfil the promise of a better world that he came to stand for.

—-

The HOPE not hate online book of condolence can be found here.

12 December 2013

An interesting reflection on the Mandela memorial service, and the hostile reception given to President Zuma, is here, from Steve Hurt of Oxford Brookes University.

http://internationalpoliticsfromthemargin.net/2013/12/12/reflections-on-the-mandela-memorial-service/

Will