Mabel Tothill was one of a small number of wealthy women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who, in their desire to improve the lives of working men and women, took up the cause of socialism and joined Bristol ILP. JUNE HANNAM tells their story.

Born in Liverpool in 1869, Mabel Tothill was the youngest daughter of a Quaker, Waring William Tothill, and his wife, Fanny, née Curtis, whose father was a surgeon. The family, including an older sister, Gertrude Fanny, born in 1865, moved to Hull where Waring was employed as a manager in a chemical works, and then on to Cottingham, near York, where he was managing director of a Starch Blue and Black lead factory.

At some time in the early 1890s when Waring had retired, the family moved to Bristol, the place of Waring’s birth. The two sisters lived separately from their parents at 19 Beaconsfield Road, Clifton, but at some point after their mother’s death in 1896 they move back in with their father at 1 Cambridge Park, Redland Road, where the household also comprised a cook and a housemaid. (Census data 1871-1901)

Mabel Tothill took an early interest in women’s rights and is noted as being a member of the Bristol Women’s Suffrage Society in the 1890s. (Beddoe: 6) She did not hold office in the movement but was present when the Suffrage Pilgrimage left Bristol in July 1913 and was friends with some of its leading members, including the Quaker sisters, Helen and Elizabeth Sturge.

Her main interest, however, appears to have been in the social conditions and education of working class men and women. After her father’s death she financed the establishment of a University Settlement in 1911 at Barton Hill, one of the poorer districts of Bristol. She was also active in the Civic League, a successor of the Charity Organisation Society, which opposed indiscriminate charity giving and aimed to provide skilled volunteers to work with local authorities. She wrote a major report on its work in 1914 and gave numerous talks on voluntary work in connection with state agencies. (WDP 21 July 1914)

It is unclear when she first became involved in the Bristol Independent Labour Party, but by the time war was declared she was part of a close-knit group of men and women who were to combine support for socialism with women’s suffrage and peace, and who would make an impact on Labour politics in the city until well into the inter-war years.

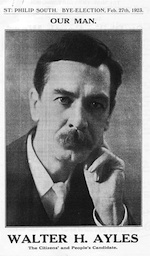

Central to this group was Walter Ayles. An engineer by trade, he was appointed as organiser, and then secretary, of the Bristol ILP branch in 1910 and made an immediate impact. (There was also an East Bristol branch, affiliated separately with head office.) Organisation was tightened up and new members were recruited so that by 1913 Bristol was described as one of the ILP’s most successful branches with nearly 600 members. (LL 17 April 1913) Ayles was elected as a city councillor in 1912 and his pamphlet, Bristol’s Next Step, became “the basis of the Labour Party’s municipal programme in Bristol over the years to come”. (Saville and Whitfield: 10)

Ayles’s wife Bertha played a part in this success and sought to attract more women to socialist and Labour politics. She was a part-time organiser for the Women’s Labour League in South Wales and soon became active in the Bristol branch, speaking at outdoor meetings, producing leaflets that explained to members how to do the work of the League, and being sent as a delegate to WLL annual conferences. (WLL Annual Reports, 1912, 1913)

At the same time she took an active role in the ILP. She was a member of the executive of the Bristol branch, took over as chairman in 1912, and was a delegate to the Labour Representation Committee. (Bristol ILP branch minutes) There were other husband and wife teams in the ILP at this time, including the trade unionist Tommy Higgins, described as a skilled labourer, a rationalist who hated churches but was very spiritual, and a hard worker on behalf of the ILP, and his wife Hannah who was vice-president of the Bristol WLL and a delegate from the ILP to the South West Federation. (‘Tommy Higgins of Bristol’, LL 14 March 1914)

Walter and Bertha Ayles might well have met up with Mabel Tothill when they attended a demonstration in favour of women’s suffrage organised by the East Bristol ILP branch at the Barton Hill baths in January 1912, and Tothill would have heard Walter speak in favour of a Bill to introduce women’s suffrage at a meeting of the Pilgrimage marchers in July 1913.

But it was the arrival of Annie Townley, an organiser for the Election Fighting Fund – set up by the NUWSS to help Labour candidates in selected seats – that was to draw her into a more prominent and active role within the ILP. The NUWSS targeted the seat because the Liberal cabinet minister Charles Hobhouse was the sitting member.

Townley, who came from Blackburn with her husband, Ernest, a cotton weaver, and her two small daughters, met a lukewarm reception from the Bristol NUWSS, many of whom disapproved of the pact with the Labour Party entered into in 1912. She therefore set up a new group, the East Bristol Women’s Suffrage Society, to carry out propaganda and electioneering work on behalf of the prospective Labour candidate for East Bristol. Tothill took on the task of secretary, and then president, and was helped by other ILP members including Hannah Higgins and Mrs Bottomley, whose husband also spoke in favour of women’s suffrage. (CC 23 May 1913)

An intensive campaign ensued over the next few months which laid the basis for Labour’s future success in the district. Townley spearheaded the movement, speaking to trade union branches and enlisting support from the WLL, the Railway Women’s Guild and the Women’s Cooperative Guild. Links were made between the campaign, women’s suffrage and other Labour causes. (CC 3 October 1913)

Townley was one of the speakers at the May Day demonstration in Bristol in 1914, and both she and Mrs Higgins attended a meeting to support locked out tramway workers. Mrs Higgins formed a women’s committee, calling on women to see this as their fight as well as the men’s. (LL 7 and 14 May 1914) Enthusiasm for the campaign increased when Ayles took over as Labour Party candidate in April 1913 and the Common Cause claimed that he “threw himself heartily into the work”. (CC 17 October 1913)

Opposing the War

Nonetheless, the outbreak of war brought to an end the campaign for women’s suffrage and propaganda for the Labour candidate in East Bristol. Tothill at first joined with other members of the Bristol NUWSS to offer their services for relief work to deal with social problems caused by the war.

She became honorary treasurer of the Committee for Women’s Employment, part of the Prince of Wales Relief Fund, and used the settlement at Barton Hill as a workroom and training area for unemployed women, especially seamstresses who could be employed to make garments for distressed Belgians and French people. (WDP 22 September 1914) This had a dual purpose – to benefit Bristol needlewomen by providing respectable work and helping an even more necessitous group abroad. She was assisted by other NUWSS members, including her Quaker friends, the Sturge sisters, and Miss Pease.

In common with many other members of the NUWSS nationally, Tothill soon found that relief work was not enough. After the Women’s Peace Congress at the Hague in 1915, the she and Townley joined other NUWSS members, including the Sturge sisters and members of the Fry family, to form a local branch of the Women’s International League which attracted 60 members.

When they were accused by the Western Daily Press of being reckless and aiding the Germans, Tothill and other Quakers wrote to the paper arguing that “women want a just and humane peace, not a German one”, and that their actions were carefully considered, “not just a passing whim”. (WDP 20 April 1915) In 1916 she attended the national conference of the Women’s International League in London and reported on the progress of the peace movement in Bristol. (WIL Annual Report, 1916)

At the same time Tothill and Townley increasingly sought to pursue their peace politics through organisations associated with the socialist and Labour movement. Indeed, opposition to the war was to bring the circle of socialists around Ayles closer than ever since they were all committed pacifists, and it gave women a more important role within the local ILP.

Ayles already had a national profile in the ILP – he was a member of the NAC from 1912-1927 – but his pacifist views gained him even greater prominence. A founder member of the No Conscription Fellowship, he was imprisoned in 1916 with four other committee members for refusing to pay a fine for disseminating a leaflet demanding the repeal of the Military Services Act. Upon his release he was refused absolute exemption from military service and he was imprisoned once again for two years, finally gaining his freedom in 1919.

Ayles’s opposition to war was first and foremost based on his Christian beliefs, which emphasised the sanctity of human life, views he shared with Tothill and other members of the ILP. He was a lay preacher for the order of Rechabites and a member of the Society of Friends. Ayles, Tothill and a new recruit to the ILP, Lucy Cox, a young schoolteacher from Keynsham, were all members of the Bristol branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Tothill’s stand on peace led her to leave the University Settlement because she did not want to “injure the university” through association. (WDP 2 October 1915) She became chair of the Bristol Peace Council, which appears to have attempted to bring together individuals from various Labour groups opposed to the war. The Council held a meeting to welcome the first Russian Revolution and the summoning of the Leeds Convention of 1917 since it was hoped that this would help the cause of peace. (WDP, 2 June 1917)

But Tothill’s most important work for peace was as secretary of the Bristol Joint Committee for Conscientious Objectors. In a leaflet listing all the men who had gone to prison from Bristol she outlined her own view of patriotism:

“We have always believed England to be a land of liberty” and despite unemployment and poverty we thought the majority enjoyed “a large measure of liberty of thought, speech and action… If we are true patriots” we will stand by “those who have surrendered their physical freedom to secure freedom of soul”. (Tothill: 5)

She worked hard to support those men who refused to fight and to make sure that those imprisoned were not forgotten. At the end of the war she took part in a meeting, attended by local churchmen, ILP candidates for the council, and Quakers, which called on the prime minister to declare a political amnesty and to release conscientious objectors. In seconding the resolution she pointed out that 41 Bristol men were still in jail, gave details of their cases, and noted that even Germany had opened its prisons. (WDP 2 Dec 1918)

Annie and Ernest Townley also went as delegates from the ILP to meetings of the Bristol Peace Council and the National Council for Civil Liberties, but she became increasingly active in the Bristol branch of the Women’s Labour League. Bertha Ayles had reduced her commitment to the League just before the war when she gave birth to a son.

By 1916 Annie Townley was president of the branch and in the following year its secretary. (WLL, Annual Reports, 1914, 1916,1917) She argued that the Labour Party should take “more definite action” to end the war, and at the 1916 WLL conference moved a resolution that the League should reaffirm its “hatred of war”, welcome mediation by neutral powers and call on the government to bring war to a speedy end through stating its peace terms. This was seconded by Hannah Higgins who claimed that the “destruction of life was an insult to mothers of all nations. The enemy were God’s people as well as ourselves.” The following year Townley organised a week’s mission with Bristol women comrades to further the objects of the Women’s Peace Crusade.

The imprisonment of so many ILP men as conscientious objectors meant that Tothill, Townley and Higgins also took on significant roles within the ILP as the war went on. They represented the party at numerous conferences and acted as delegates to affiliated organisations. Townley was elected as vice chairman in 1915, with her husband Ernest as literature secretary, but when Frank Berriman was arrested in 1916 she took over as chairman and then took on Walter Ayles’s organising work when he too was arrested.

She visited Ayles frequently in prison and acted as a conduit for his views to the local branch. At the AGM in April 1917 she received a vote of thanks from the branch for carrying on his work. At various times Mrs Higgins and Tothill chaired meetings and all three took an active role in preparations for the general election of 1918. (Britol ILP minutes 1915-18)

Peace work took a heavy personal toll, however – Ernest’s health was damaged when he was “knocked about” in London in 1916, and it was reported in the Labour Leader that he “has never been quite well since”. His problems were exacerbated when he was imprisoned as a conscientious objector in 1918. (LL 31 Jan 1918 ).

Activism after the war

Once the war was over Tothill, Townley, Cox, and Bertha Ayles, along with others such as Mrs Girdlestone, the wife of a vicar who was himself an ILP activist, remained significant in the Bristol ILP. They were responsible for ensuring that the local ILP continued to work with non-socialist groups on social problems arising from the aftermath of war.

They supported the efforts of the Fight the Famine Council and the WIL to relieve the hardships in Europe caused by the Allied blockade, and in 1922 Tothill visited Austria. In Bristol itself they took part in a campaign to improve the milk supply and to reduce its price, coordinated by Harriet Cross who had been secretary of the NUWSS before the war.

They also retained official positions in the ILP. Townley continued as chairman until 1920 when she was succeeded by Tothill who held the role until 1922. Tothill, Townley, Cox and Ayles all went as delegates to the annual ILP conferences, and in 1923 Tothill moved a resolution calling for the government to assume possession of all building material and to help local authorities build more houses. “If they did not liberate women from the bondage of struggling against dirt and bad conditions, they were wasting the life of their women,” she said. (ILP Conference Report, 1923)

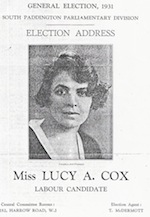

Lucy Cox was a delegate to numerous Labour conferences, took part in propaganda meetings and was secretary of the South West Divisional Council of the ILP.

At the same time Bristol’s ILP women were becoming increasingly active in Labour Party politics. Despite disagreements over attitudes to the war and to policy issues, Ayles had always argued that the ILP was the “forward wing” of the Labour Party and as such needed to keep it to its election promises. (29 October 1919, ILP minutes) He was chairman of the Bristol Labour Party from 1915 until 1923 while Townley was vice chairman in 1920.

Ayles boasted in 1923 that all the officers of the Bristol Labour Party were ILP members. As well as promoting ILP propaganda in the south west, Cox also worked to raise the profile of the Labour Party in the area. She gave talks throughout the region and was vice president of the Frome Divisional Labour Party from 1921 until 1924. (Typescript, Middleton papers, Ruskin College)

Tothill was accepted as a Labour candidate in 1919 for St Paul’s ward. She urged that women should be elected rather than co-opted onto public bodies since there was an intimate connection between many matters dealt with by the town council and the home, including nursery schools, education and housing. (WDP 24 Sept 1919) On this occasion she was unsuccessful, but she was elected the following year for Easton Ward, the first woman on the city council, although she lost her seat a few months later.

Walter Ayles was still in prison when the question of his parliamentary candidature for East Bristol was raised after the war. There were disagreements about financial support and he was not selected, but in the following year, 1919, he was adopted as a candidate by Bristol North. Cox acted for a time as his part-time agent (ILP Minutes, 23 November 1921), while she, Bertha Ayles and Townley supported his candidature by writing a women’s column in the socialist newspaper, Bristol North Forward. (February and March 1922) Here they tried to persuade the new female electorate that municipal politics affected their everyday lives and that the Labour Party would bring them the greatest gains.

Labour tensions

This period of vibrant ILP activity in Bristol, in which women as well as men played a significant role, and in which propaganda for socialism was also linked with women’s rights and peace, was not to last.

Tensions were expressed in the ILP branch minutes about what the respective roles of the Labour Party and the ILP were to be. It was suggested that the Labour Party should confine itself to registration work while the ILP undertook general propaganda. Ernest Townley thought that ILP members should take a more active role in the Labour Party but there was no agreement on this within the branch and it was generally thought that too much energy was taken away from the ILP. (Bristol ILP minutes, 1 October 1919; 8 June 1921)

Of key significance was Townley’s appointment as Labour Party women’s organiser for the South West in 1920. The job was extremely time consuming since she worked across a very large region. (Annie Townley, ‘Organising in the South West, 1920-1943’, Labour Woman, Sept 1943) This not only made it difficult for her to play an active role within the ILP, but it also meant she was expected to show loyalty to Labour Party head office.

When Tothill lost her seat on the council she was co-opted onto the education sub-committee and continued to address meetings in support of Labour candidates. She worked alongside Ayles and Cox in the social service committee of the Fellowship of Reconciliation where they continued to apply Christian principles to social questions. In a long letter to the press about unemployment in 1921 they urged the church to say whether its stand was for “God and humanity” or “mammon and charity”. (WDP 20 Aug 1921)

She sought to regain her seat in 1921 and was supported by Ayles. Their views were strikingly similar in that they wanted to end class warfare while she supported his priorities as a councillor and an MP – for better schools, greater hospital accommodation and a women’s lodging house, along with her own priority, the urgent need for better conveniences for women in the city.

It is difficult to trace any of Mabel Tothill’s public activities after 1923, although she was still speaking on platforms to support Labour candidates as late as 1927. She must have been affected by the departure from Bristol in 1924 of Walter and Bertha Ayles, and Lucy Cox, who all moved to London, where Walter and Lucy had been offered positions in the No More War Movement.

By the mid 1920s, therefore, the group of men and women who had worked closely together in socialist and Labour politics since the immediate pre-war years – linking women’s suffrage, peace and the campaign for municipal socialism – had become more fragmented, and those who remained in the city channelled most of their energies through the Labour Party.

However, they had left an important legacy. East Bristol remained a key site for Labour politics and ILP members continued to hold key positions, while Annie Townley ensured through her role as Labour women’s organiser, that some emphasis was placed on women’s potential as political activists.

Even after the war Tothill and Townley continued to raise the issue of suffrage – at the 1917 conference of the WLL, Townley seconded a resolution on the importance of women as electors, and sought to remove a clause on residential qualifications in the new Franchise Bill.

—-

Abbreviations

CC – Common Cause

LL – Labour Leader

WDP – Western Daily Press

References and further reading

Agnes M. Beddoe, The Early Years of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, The Library Press, 1911.

June Hannam, ‘“To make the world a better place”: Socialist women and women’s suffrage in Bristol, 1910-1920’, in Myriam Boussahba-Bravard, ed. Suffragism Outside Suffrage. Women’s Vote in Britain, 1880-1914, Houndsmill, Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

June Hannam, ‘“Making areas strong for socialism and peace”: Labour women and radical politics in Bristol, 1906-1939’, in Krista Cowman and Ian Packer, eds. Radical Cultures and Local Identities, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010.

John Saville and Bob Whitfield, ‘Ayles, Walter Henry (1879-1953)’, in John Saville and Joyce Bellamy, eds. Dictionary of Labour Biography, Volume 5, Houndsmill, Palgrave MacMillan.

Mabel C.Tothill, What Every Bristol Man Should Know, Manchester, National Labour Press, 1916.

Annie Townley, ‘Organising in the South West, 1920-1943’, Labour Woman, Sept 1943.

June Hannam is Professor Emeritus in Modern History at the University of West England, Bristol, and author of Isabella Ford, 1855-1924, Oxford, Blackwell, 1989.

See also: Hannam’s profile of Isabella Ford: ‘Isabella Ford – Socialist, Feminist and Peace Campaigner’.