HOLLIE BUSH tells the tale of Alf Myers, an ILPer and ironstone miner from a small Teesside village, whose refusal to fight in World War One almost cost him his life.

Many lived through the conflict of World War One. Some fought in it, some lived it out on the home front – in Teesside, for example, enduring the German naval bombardment of Tees Bay. But there were also some who refused to fight and they paid a heavy price for being war resisters. Alfred Myers was one of those.

Before the outbreak of the war, there was a large body of opinion which argued that this was not a conflict Britain should be involved with. Some viewed war – any and every war – as something sinful. These people formed the core of what were to be called the ‘conscientious objectors’, or COs. They did not loom large in the public imagination until two years into the conflict.

Before the outbreak of the war, there was a large body of opinion which argued that this was not a conflict Britain should be involved with. Some viewed war – any and every war – as something sinful. These people formed the core of what were to be called the ‘conscientious objectors’, or COs. They did not loom large in the public imagination until two years into the conflict.

The fighting in 1914 and 1915 was done by soldiers who volunteered to join the services. But by the end of 1915, the government began to feel that voluntary service produced insufficient uniformed manpower for what had become a grim, protracted struggle in the muddy trenches of France and Belgium.

So in 1916 conscription was introduced via the Military Service Act which specified that men aged 18 to 40 were liable to be called up for active service. The Act set up a system of local tribunals to adjudicate on claims for exemption on grounds of performing civilian work of national importance, health, domestic circumstances or – crucially – on grounds of conscientious objection.

In Teesside, these tribunals, made up of local councillors augmented by military representatives, were up and running by March of that year, and it was the cases of those who were conscientious objectors that attracted most public interest.

Some opposed the call-up on religious grounds, mainly members of the Quaker faith, the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Methodists. Others were socialists, members of the staunchly anti-war Independent Labour Party. The ILP had a strong presence in this area, with branches active in Loftus, Skelton and New Marske.

The people who came before the tribunals were from all kinds of backgrounds. The Redcar tribunal heard from a local hairdresser, Theodore Shewell of 5 Turner Street, who argued that, as a Christian, “he answered to a higher authority than the state”.

At one of the Loftus tribunals, 27-year-old John Espiner of 49 High Street, who came from the mineral water family, stated that his religious views led him to oppose all wars, everywhere. Similarly, John Harrison, a Loftus newsagent and member of the ILP living at 5 High Street, stated that “as a socialist he believed in the essential brotherhood of man. War killed the innocent but also shielded the guilty.” Mr Shewell’s claim was rejected while the two Loftus appeals were upheld.

A miner’s tale

But the most interesting case was heard at the Skelton tribunal. From the evidence of a sitting in early May, it was clear that members of that tribunal took a hard line with local COs. One by one, their appeals were dismissed and all were ordered to report for duty – but with the proviso that they would be placed in non-combatant roles in the Field Ambulance and First Aid Corps.

It was that day’s hearing from one Alf Myers, an ironstone miner of Carlin How, that was to have national repercussions, however. Myers was the last case of the day. He argued “that all men are of the same blood, regardless of nationality”, and said he would refuse to serve, even in something like the ambulance corps – arguments that were given little time and short shrift.

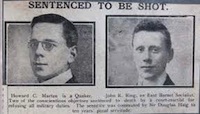

Myers, then aged 33, was listed as living at 1 Steavenson Street, Carlin How. He was a mines deputy, a position of trust, seniority and respect at the pit. A single man, he was also described as a Wesleyan Methodist and a member of the Loftus branch of the ILP. There is just one photograph, of a young looking fellow with a slight grin and a square-jawed open face.

Unlike most COs who agreed, however reluctantly, to accept non-combatant status, Myers stood by his beliefs. Accordingly, when he failed to register for military service on the due date, he was arrested and sent to Richmond Castle, which served as the depot and base for the 2nd Northern Non-Combatant Corps, attached to the West Yorkshire Regiment.

Once inside Richmond Castle (left), as a Private in the Non-Combatant Corps, it soon became apparent that he was not prepared to become the soldier the tribunal had sent him to be. Myers was one of the men who formed the hardcore of a group that has now famously become known as the Richmond Sixteen, which included members of the ILP, as well as Quakers, a Methodist, a Jehova’s Witness, a Congregationalist, a Baptist and a member of the Church of England.

Once inside Richmond Castle (left), as a Private in the Non-Combatant Corps, it soon became apparent that he was not prepared to become the soldier the tribunal had sent him to be. Myers was one of the men who formed the hardcore of a group that has now famously become known as the Richmond Sixteen, which included members of the ILP, as well as Quakers, a Methodist, a Jehova’s Witness, a Congregationalist, a Baptist and a member of the Church of England.

They refused military drill and to wear uniform. As a punishment for their resistance the men were put on a bread and water diet. Eight were put in detention cells while seven were crammed into the Guardroom.

But the real ordeal began when these absolutists were taken from the Castle. On 29 May 1916, a comrade of Myers, one Clarence Hall, wrote on the wall of cell no. 6: “Sent to France”. The writing is still visible on the crumbling plaster to this day, although public access is not allowed for reasons of preservation.

The men were taken to Southampton and the very next evening loaded onto the torpedo boat St Tudno for the Channel crossing to Le Havre. After staying overnight at the Cinder City Camp, they were moved the next morning by train to Boulogne. The COs continued to refuse orders throughout.

Lies and punishment

At Henriville Camp they were warned that, as they were now on active service, the penalty for refusing to obey orders was death. They were also told a blatant lie – as they later learned – that a previous group of absolutists had given way to such a threat by accepting their position in the Non-Combatant Corps.

They were given 24 hours to decide, and told that their past errors would be swiftly forgiven if they now toed the line. Yet they remained steadfast, and their conversation and actions evidently inspired many COs from other religious and political persuasions.

Early in the morning of 6 June 1916 the men were woken by a sergeant major for parade. The COs formed a line while a sergeant asked each CO individually if he was prepared to serve. Following their refusal, the top brass that night decided to put them in front of a Field General Court Martial. The charge was the gravest one for any soldier: ‘Refusal to obey his superior officer in the face of the enemy.’

On 12 June charge sheets were given to the COs, and the next day an escort arrived at the Field Punishment Barracks to accompany them to the court martial. As they climbed a hillside en route they saw the English Channel, which must have caused them to wonder if they would ever see their homeland again.

On 12 June charge sheets were given to the COs, and the next day an escort arrived at the Field Punishment Barracks to accompany them to the court martial. As they climbed a hillside en route they saw the English Channel, which must have caused them to wonder if they would ever see their homeland again.

When they reached their destination, each was read the charge: “No. … Private … 2nd Northern NCC, under Section 9(1) Army Act. Disobeying, in such a manner as to show a wilful defiance of authority, a lawful command given personally by his superior officer, in the execution of his office, in that he, at Boulogne, on 6 June 1916, refused to serve or don uniform.”

There followed a perfunctory trial, in which the COs disputed their alleged status as soldiers, but were inevitably convicted. They were then led back to their cells in preparation for the sentencing day, Saturday 24 June.

One CO recalled later that the army made a great show of the proceedings so as to deter others from following their example. According to external records, these COs were marched out in front of hundreds of troops lined up on three sides of a large square. The COs were led up to a raised platform on the fourth side of the square where a high-ranking officer met them.

When silence was established in accordance with military order, the crime and punishment of each CO was announced: “Private …, No. …, of the 2nd Northern NCC, tried by Field General Court Martial for disobedience, sentenced to death by being shot.”

The statement was followed by a long drawn-out pause, after which it was stated that the sentence was confirmed by General Sir Douglas Haig. Another, even longer, drawn-out pause followed, after which the words “and commuted to 10 years penal servitude” were added.

The tension of the previous five weeks was at last over and, although difficulties remained, the men’s anxiety at not knowing their fate was finally broken. The COs, including a humble Carlin How miner, had called the bluff of their military superiors, who had taken them all the way to the place of execution and then, at the very last minute, decided not to pull the trigger.

In the event, they served their penal servitude in harsh conditions, many breaking stones at Dartmoor Prison. Myers did not go there, but was sent to a penal work camp at Dyce, near Aberdeen, a place with a fearsome reputation for bone-breaking drudgery.

He was later moved to Northallerton Prison, and then, for some reason, to Maidstone jail in Kent. His sentence was commuted in the spring of 1919 and he was then released.

At that point Alf Myers vanishes from local history. Did he come back to his village? Did he go back into the mines? Did he stand by his beliefs and continue to play his role in the church and the local ILP? No one knows and no records exist.

I wonder if there are any descendants of Alf Myers around today who can fill in these blanks. All one can say is that, even though he would not fight for something he believed to be inherently unjust, he was no coward. He was prepared to die for those beliefs and indeed came very close to doing so.

—-

The author is a member of the Hannah Mitchell Foundation and of the Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland Constituency Labour Party.

This article was previously published on the People’s Republic of Teesside blogspot and in the June 2015 edition of Coastal View and Moor News in East Cleveland.

30 June 2017

In 2003 I undertook my MA dissertation on WW1 COs and especially focused on the Richmond 16. I would happily share this with ILP and in line with further voluntary work I am currently doing for the WEA on what happened to north east COs after the war as part of their Turbulent Times 1918-1928 project.

Re Alfred Myers I have included a brief reference from my dissertation below:

After being released from prison in April 1919 he appears to have integrated himself back into his community and took up positions as a Sunday School superintendent and trustee of his local church. He was musical playing the piano and sang tenor in the Wesleyan Carlin How choir. Relatives described him as a man who “stuck to the rules”.