Charitable giving keeps corporate capitalism and wealthy individuals in control, but adds nothing to the health of society, says STEVE THOMPSON. And so did Clement Attlee.

From Victorian times to the present, the concept of charity has fitted comfortably within capitalist orthodoxy. Large companies have always made token gestures in the way of donations to worthy causes. Charity giving was very popular within Victorian capitalism and it still is today. It keeps corporate capitalism and wealthy individuals in control, but adds nothing to the health of society.

From Victorian times to the present, the concept of charity has fitted comfortably within capitalist orthodoxy. Large companies have always made token gestures in the way of donations to worthy causes. Charity giving was very popular within Victorian capitalism and it still is today. It keeps corporate capitalism and wealthy individuals in control, but adds nothing to the health of society.

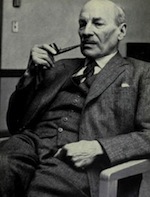

Clement Attlee was politicised when he was a social worker in London’s east end in the early years of the 20th century. It was at that time that he joined the ILP. His socialism even then was astute and mature.

Published in 1920, The Social Worker was the first book he wrote, and what he had to say about charity is as true today as it was then. He attacks the idea that looking after the poor can be left to voluntary action and quotes as evidence a charitable clergyman, who said: “Porridge served to the poor should always be a little burned to put off those who were not in dire need.”

Attlee argues that if a rich man wants to help the poor, he should pay his taxes gladly, not dole out money at a whim. In The Social Worker he writes:

“Society as constituted was accepted, and the existence of the poor taken for granted, nay even welcomed, as providing an outlet for the benevolence of the rich. Charity is always apt to be accompanied by a certain complacence and condescension on the part of the benefactor, and by an expectation of gratitude by the recipient, which cuts at the root of all true friendliness. The charitable of the [Victorian] time seem to us to be smug and self-satisfied. They delighted in sermons to the poor on conventional virtues, lacking sharp self criticism.”

It is unfortunate, he says, that “there should be a certain kudos obtained from giving to charity which is absent from the performance of a duty; thus as man will oppose an increase in taxation or local rates while he is prepared to give far more than these increases in charity. Very many do not realise that you must be just before you are generous.

“In a civilised community, although it may be composed of self-reliant individuals, there will be some persons who will be unable at some period in their lives to look after themselves, and the question of what is to happen to them may be solved in three ways:

- they may be neglected

- they may be cared for by the organised community as of right

- they may be left to the goodwill of individuals in the community.”

The first way is intolerable, he says, as for the third:

“Charity is only possible without loss of dignity between equals. A right established by law such as an old age pension, is less galling than an allowance made by a rich man to a poor one, dependent on his view of the recipients character, and terminable at his caprice…”

Charity, he writes, “tends to make the charitable think that he has done his duty by giving away some trifling sum, his conscience is put to sleep and he takes no trouble to consider the social problem any further.”

Attlee quotes Robert Louis Stevenson stating that “gratitude without familiarity … is a thing so near to hatred that I do not care to split the difference”. The rich, Stevenson had written, should instead “subscribe to pay their taxes. These were the true charity, impartial and impersonal cumbering none with obligation, helping all.”

Foundations of a decent society

Attlee thoroughly approves of people doing voluntary work among the poor, as he had done for many years, but it must be underpinned by paid staff – and properly paid staff at that. Why should we expect that people doing worthwhile jobs for the community should not be as well paid as those whose jobs are about making money?

Charity from religious organisations is not the answer either. He quotes the Bishop of Southwark: “We clergy lack the imagination to see all it means for those suffering from social injustice … we, as a whole, instinctively sympathise with the employers.”

For religious people, charity is a way to salvation “so that throughout the ages of faith one finds a large amount of charitable work being done with the principle object of benefiting the soul of the giver, the effect of the welfare of the recipient being a secondary consideration.”

So if you can’t leave the poor to starve and die of treatable illnesses, and live in squalor, that leaves the other option – state welfare payments are not charity.

The citizens of a decent society should be able to expect health and social services and welfare, not as a by product of the largesse of wealthy individuals and companies, and certainly not to generate profits for private companies, but because they are needed. Before the NHS, qualified nurses and doctors were spending their valuable time collecting money to run the hospitals. It is the responsibility of a decent society to ensure that the state provides the means to run the necessary services.

The 1945 Labour government has been criticised because the welfare state it created was ordered in a highly centralised way. I think that at the time, this is the only way that it could be done, considering the time scale available to them. If the Labour government had been able to continue, I think there could have been a flourishing of community self-help organisations along the lines of co-operative development.

Through the focus of the 1945 Labour leadership, a sound foundation was built for society. That foundation was subsequently eroded away.

—-

The Social Worker by Clement Attlee was published in 1920.

Some quotes used here are from: Clem Attlee: Labour’s Great Reformer by Francis Beckett, Haus Publishing 2015.