Volunteers who fought in the Spanish civil war were political soldiers striking a blow against oppression across the continent, according to BOB HARRISON.

The Spanish elections in 1936 brought to power a left-leaning popular front government with a mandate for reform. Associated episodes of political violence carried out by groups on both the left and right gave right-wing army officers the opportunity to stage a coup against the elected government.

The main leaders were Generals Mola, on the peninsula, and Franco, in north Africa. After initial successes, the coup stalled with loyal elements of the army and the police and popular workers’ militias successfully opposing the rebels and reversing early gains in some areas. There was a brief stalemate with the government controlling the capital and industrial areas and the rebels holding the smaller, more traditional regions.

The main leaders were Generals Mola, on the peninsula, and Franco, in north Africa. After initial successes, the coup stalled with loyal elements of the army and the police and popular workers’ militias successfully opposing the rebels and reversing early gains in some areas. There was a brief stalemate with the government controlling the capital and industrial areas and the rebels holding the smaller, more traditional regions.

The balance of the conflict shifted in favour of the generals when British sympathisers hired an aircraft to fly Franco from the Canary Islands to north Africa and Hitler supplied aircraft to lift the mercenary army of north Africa to the peninsula. These were the most disciplined and experienced troops in the theatre and gave Franco the ability to conduct a civil war.

The republican government responded by arming popular militias attached to political parties and trade union groups, and eventually developed a new popular army with a chain of command.

Volunteers from many countries supported the republic. Some were attending the Workers’ Olympiad in Barcelona, which had been organised in opposition to the Berlin Olympics. This was forestalled by the coup attempt in July, but some of the athletes joined local militias to fight on the Aragon front.

Others were in Spain for different reasons. Felicia Brown, for example, was an artist from the Slade working in Spain who joined a militia unit in Barcelona. She was killed in August 1936 in the first months of the war, and was the first British casualty of the conflict.

The Spanish government was short of international friends. The USSR and Mexico were the only candidates, although the republican government was initially doubtful about Stalin’s commitment. Stalin did not want to antagonise Germany and had hopes of an alliance with France and Britain.

The republic and Spanish anarchists were suspicious about Soviet influence strengthening the Spanish Communist party, but growing German and Italian support for the generals, in contravention of the non-intervention treaty, forced their hands.

International brigades

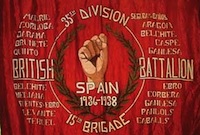

The Comintern met in September 1936 to discuss sending volunteers to Spain. The first brigade, the XI, was formed in October and eventually there were five international brigades out of 225 in the republican army.

The Comintern organised recruitment through national Communist parties and a clearing office in Paris. Volunteers congregated in Paris and were then sent to Spain by rail and foot or rail and sea. Some, such as Laurie Lee, made their own way, and recruitment was often spontaneous, although many approached local CP branches and overall 50% of volunteers were Communists. The British Communist Party, for example, had a lot of control over the British battalion.

The Comintern organised recruitment through national Communist parties and a clearing office in Paris. Volunteers congregated in Paris and were then sent to Spain by rail and foot or rail and sea. Some, such as Laurie Lee, made their own way, and recruitment was often spontaneous, although many approached local CP branches and overall 50% of volunteers were Communists. The British Communist Party, for example, had a lot of control over the British battalion.

At any one time there were between 12,000 and 16,000 men in the brigades, while recruitment reached its peak in peak 1937. Recruits came from 53 different countries. The largest groups were from France and Belgium but there were also large contingents from USA and Canada.

The total over the whole period was 30,000 to 40,000. Some 2,500 went from Britain and Ireland. Overall 8,000 were killed and 3,500 wounded. Another 5,000 volunteers served with militia units supporting, for instance, the POUM. George Orwell was one of these. Many men and women volunteered in non-combat roles, as doctors, nurses and ambulance drivers, all very dangerous jobs.

Helen Graham argues that the origin of the movement was in the European diaspora formed from the mass migrations of people caused by the First World War and the resulting economic and political disruption.

This was a time when fascism and other dictatorships were spreading across Europe. The only democracies that remained were France, Netherlands, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Scandinavia (minus Finland), and the UK. Thus, left-wing internationalism was a cause to be fought for against right-wing regimes which had replaced disintegrating European empires and their now defunct capitalist systems.

The volunteers were political soldiers striking a blow against political and economic oppression across the continent in an ongoing European civil war. After Russia, Italy, Germany and Hungary, Spain was the new front line. Reactionary political elites across Europe saw it in the same terms, which explains the ambivalence of the main democracies – France and Britain – to the Spanish republic.

The brigades were organised into companies and battalions. A company was made up of 100 to 150 men, a battalion of four companies, and a brigade of four battalions, with the normal hierarchical structure of commissioned and non-commissioned officers. In addition, following the New Model Army and the Red Army, units had political commissars who were responsible for political education and morale, and sometimes played a role in military decisions.

The nationalist rebels were supported by 20,000 German and 75,000 Italian troops. Some were recruited to serve in Spain but many were regular army. The German troops were mainly technical advisors, but the Italian troops were used in normal combat. The conflict was only ever a sideshow for Germany, but Italy was involved in a full-scale war with the republic. In addition, 20,000 Portuguese troops and 80,000 north African mercenaries also fought for the rebels.

The battles

The pattern of the war is confusing. The nationalist strategy of Franco was a series of offensives aimed at capturing republican population centres and then, by systematic repression, expunging the politics of republicanism from the nation. It was a political crusade. As the legitimate government, the republic needed to hold on to ground which tied up their troops, while the nationalists had more freedom to deploy.

Initial, successful republican advances, mounted to capture the initiative, were stopped by nationalist reserves, resulting in stalemate or withdrawal. The two sides had equal numbers but, despite Soviet support (paid for by drawing on Spanish gold reserves lodged in Moscow), the republicans were weaker in terms of equipment and reserves of ammunition.

The international brigades were used widely in a number of battles, often as shock troops or to hold difficult positions, so casualties were high.

The earliest were responses to a nationalist attempt to take Madrid, which was very nearly successful. In November 1936, an attack by north African troops caught the government unprepared, and was only held by the Communist-armed militia, the so-called fifth regiment, the XI international brigade and by the people of Madrid. Much was made of the boost in morale which the brigade brought to the Madrillanos.

The attack was renewed in December when the nationalists tried to cut off the Coruna road and isolate the capital. The result was a stalemate with many losses on both sides, particularly among the international brigades. The British battalion was formed in December and went into action in February 1937 in the battle of Jarama when an attempt was made to cut the Valencia road to the south of the capital. Losses were high on the republican side, and the British battalion of 500 lost 136, while a similar number were wounded.

In March 1937, republican successes against Italian forces at Guadalajara were offset by rebel gains in the north of the country. The Brunete offensive was launched to take pressure off the northern front. Despite initial gains, the deployment of rebel reserves reversed these. The republic attacked again in Aragon that August but could not prevent the rebels from finally taking Asturias, thus losing its last base on the Biscay coast.

The republic attacked at Teruel in December 1937 to stop the rebels from splitting the republic in two, but the same story was repeated – after initial gains the rebels retook Teruel. In March 1938 the rebels staged a massive offensive in Aragon and forced a series of costly retreats by republican forces.

By April the rebels had reached the Mediterranean and cut the remains of the republic in two. The last attempt to win victory, or at least to force a negotiated peace, came in July 1938 when the republicans advanced over the river Ebro. The battle lasted three months but in the end the republican army was overwhelmed by rebel forces and the offensive collapsed. The war dragged on for another six months, and Franco entered Madrid in April 1939.

Some volunteers

While the recruits who served in international brigades were mainly working class, many unemployed, all classes were represented and some volunteers left secure jobs and careers to fight in Spain. Here are some of those who volunteered from Britain:

Jack Jones, a Liverpool Labour councillor, served in Spain from March till August 1938. He fought at the battle of the Ebro where he was badly wounded. Repatriated, he subsequently had a distinguished career as trade union leader and Labour politician.

Lou Kenton fought against Mosley’s fascists in the battle of Cable Street in 1936. He rode his motorcycle to Spain in February 1937 where he worked as a dispatch rider and driver in the medical services. He was one the many Jewish Communists who joined the brigades.

Esmond Romilly was a schoolboy radical. A nephew of Winston Churchill, he went to Spain in 1936 at the age of 17. He fought in the defence of Madrid with the German Thaelmann battalion and saw many of his comrades killed. He joined the Canadian air force in World War II and was killed at the age of 23.

Harold Fry, a 33-year-old Communist who had served as a sergeant with the British Army in China, went to Spain in December 1936 and commanded the British machine gun battalion at the battle of Jarama. He was wounded and captured, along with most of his company, in February 1937. Sentenced to death, he was exchanged for a rebel prisoner and repatriated. He broke his undertaking and returned to Spain in August 1937. He commanded the British Battalion only to be killed at the battle of the Ebro that October.

Bert Overton was a company commander at the battle of Jarama where he succumbed to battle-induced stress. His comrades felt that his cowardice led to the capture of Fry’s company. He was court-martialled by officers in the brigade and sentenced to a labour-punishment battalion where he was killed a week later.

Walter Tapsell was circulation manager for the Daily Worker and former leader of the Young Communist League who had studied at the Lenin School in Moscow. A member of the central committee of the British Communist Party from 1928 to 1933, he went to Spain in 1937 and became British battalion commissar. He fought at Teruel and was killed at Calaceite in April 1938.

Bob Cooney was a leading member of Aberdeen Communist Party. He went to Spain in October 1937, took over as battalion commissar when Tapsell was killed, and finally became the brigade commissar. He was repatriated when the brigade was disbanded in 1938.

Frank Ryan was a senior member of the IRA who fought on the republican side in the Irish civil war. He went to Spain in December 1936 and was wounded at Jarama in 1937 where he played an important role in rallying the British battalion. He was captured at Calaceite in March 1938 and imprisoned in a camp near Burgos. He was released through the good offices of the ABWER and moved to Berlin in 1940. He died in Dresden in 1944 from an illness exacerbated by his war wounds.

Malcolm Dunbar went to Spain in January 1937. As a section leader of the British battalion he was wounded at Jarama. He was the first commander of the British anti-tank company and eventually became chief of staff of the XV brigade. He was a highly regarded officer in Spain but only able to become a sergeant in the British Army during World War II. He committed suicide after the end of the war.

The republic eventually disbanded all international units as part of its attempt to negotiate peace, and the remaining members of the British battalion were repatriated in December 1938, although some remained in prison until March 1940. While many were blacklisted by the establishment this was by no means true of all.

Tom Wintringham, a former battalion commander at Jarama, became the main force behind the formation of the home guard in 1940. Bill Alexander, another battalion commander, served as a captain with the British Army in Italy, France and Germany during World War II. Len Crome served during the war as a captain in the medical corps.

The International Brigades Association was formed in March 1939 and has a long history of campaigning to support political prisoners in Spain.

—

This article was originally written for a talk delivered to a Durham Workers’ Education Association branch study group in February 2016.

Information about the International Brigades Memorial Trust is here.