HARRY BARNES continues his investigation of the state of Labour, looking at the failures of the Miliband leadership, the basis for Jeremy Corbyn’s triumph and the prospects for party unity.

I have never met Ed Miliband and only went to hear one or two of his platform speeches. However, I do feel that he was carefully trying to move the party away from New Labourism towards something nearer the old Smith-Beckett stance. Perhaps it was only a start on a much longer road.

For example, he showed a strong commitment to fighting climate change as a minister in the two years before he became leader – which is a key issue Labour needs to face up to. And the proposals developed by his policy forums in the run-up to the 2015 elections (reflected in Labour’s general election manifesto) seemed to me to unlock a door that socialists could begin carefully to push open.

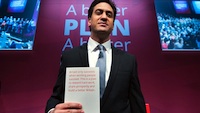

Although Labour’s programme didn’t include all the policies we needed and could have delivered, it nudged us in the right direction. He even managed mixed claims for:

- a strong economic foundation

- higher living standards for working families

- an NHS with time to care

- controls on immigration

- a country where the next generation can do better than the last

- homes to buy and actions on rents

… all then inscribed on his ill-conceived ‘Ed Stone’.

But I feel there are more inspiring details in the ideas put forward by the policy forums, which Labour conference endorsed. They are tucked away in amongst the 180 policy proposals I drew out before the election and discussed in detail here.

The problem was Labour did not make use of these policy stances to inform and enthuse its members or to persuade the media, nor as part of its wider campaigning material. It also completely failed to use policies developed for the European Union elections and the Scottish referendum campaign.

In terms of parliamentary seats, under Miliband Labour endured its worst election result since 1987 when it was still recovering from the blow suffered in 1983 in the wake of the split caused by the defection of MPs to the Social Democratic Party. The responsibility for failure in 2015 rests with Miliband, but he was also badly served, especially by Douglas Alexander, his campaign manager, who even lost his own seat in Scotland.

So where are we now?

As we know, Jeremy Corbyn was able to stand for the Labour leadership only because MPs such as Beckett gave him a sympathy nomination, expecting him soon to bite the dust. Yet, after 32 years at the very back of Labour’s back-benches (never having had even a minor front bench position), Corbyn took the leadership with an across the boards victory, although he was only the choice of a small minority of Labour MPs.

Much of his political work over more than three decades had been done outside the Commons (although he did make regular contributions in the House), as a political campaigner in the country and overseas, regularly addressing of meetings and rallies. He was also a dedicated Islington MP on his own patch.

His experience was tailor-made for the form of campaigning he needed to win the leadership in 2015 and again this year. He attracted people looking for a socialist Labour Party – people disillusioned with New Labourism and with Miliband’s failure. At first people thought these ‘Corbynistas’ were overwhelmingly young people, but recent research has indicated that the age and background of new Labour Party members is very similar to that of the established membership – they are often middle aged and older people from rather middle-class backgrounds.

Corbyn found that while rallies were one thing, handling the Commons was quite another. He had plenty of experience of hounding those at the despatch box, but none of being the person hounded. Then there were issues on which he would not compromise – he was against bombing in Syria and opposed to renewing Trident regardless of Labour policy indications (on Syria it was a complex position). He was particularly keen to exploit to the full the Chilcot Report on Iraq, although some 60 MPs still on the Labour benches had voted with Blair for the invasion, including Beckett.

Only nine months after becoming leader, the PLP held a vote of no-confidence in Corbyn and no less than 172 MPs voted against to 40 in his favour, with almost 20 non-voters. Only 16% of Labour MPs were non-rebels – and a number of those were half-hearted – meaning Corbyn had a very low support base.

Yet he made some compromises, and in particular moved to support Britain’s continued membership of the EU (something he had always opposed). He adopted what, to me, was an appealing stance – arguing for continued membership while pressing for a democratised and social Europe, plus supporting closer relations with the Party of European Socialists (PES). But as a campaigner he was less than vigorous in pursuit of his new positions, despite having the campaigning skills.

After the mass resignations from his front bench this summer, and his re-election as leader, Corbyn has now put together a fresh shadow cabinet team, the make-up of which is of some interest.

Back in March 2016 a leaked document, said to have come from Corbyn’s office (although he denied it), divided Labour MPs into five categories, from those described as key supporters to those seen as most hostile. The lists are perceptive, whoever constructed them.

The MPs recently appointed to the shadow team fall into those categories in the following proportions (I have excluded those who have since died and Sadiq Khan who resigned):

(a) core group: 13 out of 18 current MPs (72%)

(b) core group plus: 27 out of 55 (49%)

(c) neutral but not hostile: 15 out of 71 (21%)

(d) core group negative: 5 out of 48 (10%)

(e) hostile group: one out of 35 (3%)

Three MPs who have joined Corbyn’s shadow team are excluded from the above figures because they arrived in the Commons via more recent by-elections – Rosena Allin-Khan, for example, who had only 24 days Commons experience before becoming Shadow Minister for Sport. And at least two of the names are missing from the leaked list, including Fabian Hamilton who is now Shadow Defence Minister.

As we can see, only six of Corbyn’s 83 appointees (7%) were in the ‘negative’ and ‘hostile’ categories (d) and (e) (although we don’t know how many were approached and refused), and only Rosie Winterton – moved from shadow chief whip to be Labour’s envoy to our sister parties in the PES – is from the ‘hostile’ group. In fact, her new post could be of real significance as the party works with labour movements inside and outside the EU.

If there had been a similar list under Blair, his cabinet may well have displayed a similar bias. Chris Mullen went from the Socialist Campaign Group to the front bench but he, like Winterton, was an exception to the rule. But then Blair had far higher numbers of core supporters. Compared to Blair, Corbyn has his work cut out to create even a vision of reasonable unity in the PLP.

Finally, I’d like to consider the role that Momentum now plays (a) in mobilising support for Corbyn, (b) in seeking to shape the future direction of the party, and (c) in helping (at least) in some areas to stimulate canvassing and campaigning activities for Labour.

I receive national, Derbyshire and Sheffield area material from Momentum, rather as if I was a member – although I am not – and so far have attended two of their open meetings. I am keen to maintain a watching brief on their activities as I recognise the organisation may well be different in different areas. No doubt some trends will be welcome and others less so.

Other people’s assessments of the PLP, the involvement inside the Labour Party of old and new members, the work of Momentum and of other groups around the party, plus Labour’s wider links with bodies such as the PES, would all be welcome.

—-

Harry Barnes is the former Labour MP for North East Derbyshire. He blogs at ‘Three Score Years and Ten’.

This is part two of a two-part article. It is a longer version of the presentation made by Harry to an ILP conference on Labour’s crisis held in Leeds on 15 October 2016.

The first part of Harry’s piece is available here.

See also: ‘Labour on the Brink: A Statement on the Leadership Crisis’.

14 January 2017

Clearly we need to find comradely ways of knocking the heads together of Corbynites and anti-Corbynites in the Labour Party, whilst trying to spell out a synthesis.

In frustration, this is an email I shot off to Tristram Hunt:

“I cannot understand anyone resigning from parliament except for serious health reasons or under other special adverse personal circumstances. If an MP decides to resign from the political party that helped to get them elected, then that can be another reason.

“If an MP does not like trends within their own political party, they can still use parliamentary avenues to seek to tweak its approach on various areas of concern – as I did for most of my 18 years as an MP.

“Then an MP has a clear duty (until the next election) to seek to serve what they judge are the best and legitimate interests of their constituents, who helped them into the post in the first place.

“Resigning for personal career purposes is an affront to the parliamentary system. And even if a better way has been found to serve society in a new job, then it (or a possible alternative) should be held off until after the following general election. That is when an MP next finds that her/his moral contract with their electorate has ended – or at least requires renewal.

“I thought this would be clear to anyone in the Labour tradition who has an understanding of political theory and political philosophy.

“None of this is a secret code from by me because I voted for Jeremy for leader. Because I never ever did.

“I hope that you will give the matter of your resignation further serious thought.”

10 January 2017

Hello Ken. We have masses of people who fall into the categories of being (1) unemployed (going well beyond the registered figures), (2) have insecure and badly paid jobs (including those on zero hours and those forced into forms of badly defined ‘self-employment’), with them not having any security nor built-in welfare provisions, (3) those moving in and out of badly paid jobs with periods of unemployment, (4) those working excessive hours in more than one job to try and make ends meet and (5) those with better jobs and conditions who can be thrown onto the scrap heap at any time – even those who eventually find fresh and reasonable work are often continually jumping between such extremes.

It is not surprising that many in these categorioes are completely disillusioned with the general run of our parliamentary politicians. In the absense of any seeming alternative prospects they often turn to the extremes of Brexit, Boris, Trump, Farage and even look for clearer ‘sort-them out’ forms of fascism. This pattern runs at least across the western world, with many differing and even deeper problems elsewhere.

Although the media hype probably distorts Corbyn position, his latest proposals on immigration won’t cut much ice with many of the above. As we are going out of the EU why does he not attempt to both attract this new form of lumpen proletariat and also pull it in a constructive direction? As we go out of the EU, then the remaining EU nations could have the same controls placed over their people’s migration to the UK that many other outside nations already have. Yet special provisions could be made for those in an immediate crisis situation. A reasonable UK share of refugees from Syrian and other disaster areas could be catered for. And the argument put as to why these are a special case.

Corbyn also needs to clarify his position on restraining the wealth of the filthy rich. Their wealth normally comes from several sources and needs to be tackled by progressive forms of taxation, which can be shown not to be aimed at the rest of society. It woud help pay for both (a) the settlement and intrigration of refugees into our society and (b) for the creation of more and better jobs and ranges of social provisions – including moves to decent homes (as with Wheatley’s 1924 Council Housing Legislation and in the subsequent post-war building of the welfare state).

7 January 2017

I have and continue to think through the challenges which confronts Labour. Harry Barne’s description of the lumpen proletariat as the dispossessed is interesting in the present context. While the nature of the kind of work has changed, the dismantling of the of the industrial revolution created many thousands of redundancies most of whom were unable to get work again. A lumpen proletariat of dispossessed former workers lost their dignity and for many their self respect. They no longer any place for them in a society where what you did at work was the means by which you were valued. During the Thatcher, Major, Blair years well over a million former manual workers were condemned to live a life of idleness. It was this group who were awakened by the financial crisis of 2008 and the scandals around kick backs and parliamentary expenses. Many hadn’t voted for years and in 2010 even more didn’t vote thus sealing Labour’s fate. By the time of the referendum on Europe the slumbering proletariat were fully awake and stirred by the razza mattaz of Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage turned against the political establishment. I have maintained for many years that in politics how you are perceived by the electorate is seen by them as more important than what you may say. Labour’s problem today is that the party is being perceived as being part of the establishment.

15 December 2016

Hello Ken: Karl Marx saw the proletariat as the key avenue that socialists should work with (and through) to advance the transition to socialism. They were then a growing mass section within a number of nations who were becoming dominated by capitalist interests and fully explioted by them. Trade unions, Chartists, Labour movements, Communist Parties and the like needed to develop socialist understandings and work in and through such avenues for advances and improvements for working people. This could have led to the breaking of the chains of capitalism.

But Marx also argued that there was a “class fraction” of the proletariat who were mainly placed outside of the above framework, being permanently unemployed and even more destitute. These were the “lumpen proletariat”, people who it was diificult for socialists to mobilse and link with. They were the most depressed and isolated people in developing capitalist societies. It would be the proletariate itself that Marx saw as the avenue for breaking the chains for the lumpenproletariat. But they were not a section of society which socialists could easily link into and mobilise – apart from those who found their way back into more normal proletarian positions.

In the Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx describes the lumpenproletariat as a “class fraction” which aided the political power base for Louis Bonaparte of France in 1848. In this sense, Marx argued that Bonaparte was able to place himself above the two main classes, the proletariat and bourgeoisie, by using the “lumpenproletariat” as an apparently independent base of power. While in fact advancing the material interests of his own clique.

Germany was hit by the burden of reparations after the First World War and was then smashed by the wide impact of the 1929 Wall Street crash. Masses of the German people were unemployed, destitute and deprived and lost. This new form of a destitute lumpen-proletariat helped to usher Hitler into power. And were found work, including the building of his totalitarian military regime.

The world is, of course, very different today. But we have seen the fracturing of the industrial working class in the UK and elsewhere. With its great decline has gone many of the better aspects of the welfare state, the NHS and the mixed (Keynesian-syle) economy. There are greatly expanded groups of deprived people. Those who are in unemployable positions, people on zero-hour contacts, those who in theory who are “self-employed” but really work under the control and demands of firms (but have to try to find their own insurance and pensions cover), those with qualifications way beyond the level of any job-openings they can find, masses holding down temporary positions and never being able to prepare and plan for the future and young people unable to get a realistic hold on a jobs ladder.

The old techniques of seeking to mobilise trade unionism, the co-operative movement and (hopefully) a socialist-leaning Labour movement, all still have relevance. But we need to go beyond that. How do we engage and take on the concerns and well-being of those I mention above? And also how to do we involve those from other nations who face similar circumstances? All created by the common influences and controls of multi-national capitalism.

We need (a) to understand the modern world and its growing direction, (b) engage with the differing sections of deprived people, and (c) join with overseas Labour movements and others who share in similar problems – irrespective of moves such as Brexit, although it has to be part of our agenda.

The Labour movement (and Jeremy) are in need of such understandings. Yet we all need to do this in ways which build upon and develop what is still left of the Labour movement. Then we have to fit Syria-style conflicts and the mass refugee crisis into our analysis. Yet to the modern neo- lumpenproletariat, these are seen as a further threat to their well-being.

10 December 2016

Corporatism and the demise of democracy!

The onward march of Amazon and other global businesses along with the current blizzard of new technology is overwhelming much of society. Our democratically elected institutions are being rendered impotent by the speed and depth of change. We find ourselves unable to ensure that the general public receives the protection we expect to receive from our respective governments. Democracy as a civilised concept for living together is being challenged by the way the technology engages people individually. Each individual becomes a commodity engaging with big business through the use of the latest technology. Of course these methods appear convenient, as indeed they are on an individual basis, however from a community or even national standpoint the application of new business methods are liable to have devastating consequences for the common people.

19 November 2016

At the Rose Bowl seminar in October 2016 I don’t think we gave any real attention to the question of the electoral unpopularity, not just here in the UK but in Europe and further afield. There is a universal unpopularity of almost all politicians. I don’t think it can be denied, the Labour Party at a parliamentary level is a form of political elite which in itself is a concept at odds with the idea of democracy and democratic socialism. Across Europe democratic socialism is in retreat, yet those of us who have been around for a while say that we believe the need for democratic socialism is greater than ever.

It was Ronald Reagan, supported by Thatcher, who rejected the Keynesian economic and political agenda. They accepted as gospel Prof Hayek’s opinions in his book first published in 1960 (The Constitution of Liberty). Neoliberalism was created out of the belief that Hayek’s views would be better than Keynes’s method of wealth creation. I believe that Keynes was wiser and certainly more experienced than Hayek and viewed the financial, economic and politics from a completely different perspective than Hayek. In short, the men saw the world differently.

Now it is becoming clear that neoliberalism doesn’t work. Clearly Hayek’s trickle down theory doesn’t work, neither does his concept of liberty. It only works for the rich. The richer you are allows you to take more liberty. This contradicts with democracy and equal rights. Labour and the other democratic socialist parties across Europe and the world are in need of a new vision for a new age.