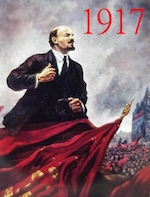

IAN BULLOCK marks the centenary of the Russian Revolution by arguing that the profoundly anti-political stance that took root among Leninists had dire and lasting consequences for socialism in the west.

It seems reasonable to assume that most people who become aware of the centenary of the 1917 Russian Revolution during the course of this year will take it for granted that the whole Leninist enterprise was a total failure. Given the genuine hopes and expectations of people on the Left at the beginning of the last century, from a socialist point of view it was not so much a failure as a disaster.

After all, the societies we’ve ended up with in China or in Putin’s Russia bear even less resemblence to those that socialism seemed to promise in the early years of the 20th century than the capitalist countries of the ‘developed’ world – even with the advent of Trump! Neither the ‘Cultural Revolution’ nor the Stalin purges resembled anything that pre-1917 socialists had in mind when they looked towards the socialist future.

There will be some on ‘the Left’ who will urge that all would have been well without Stalin, that ‘true’ Leninism never had a fair chance, and that we should all redouble our efforts to make sure it will be triumphant in the 21st century.

Of course it is true that the record of socialism in western Europe, and of that part of the Left that variously calls itself democratic socialist or social democratic, is not that impressive either. The best summary I know of its achievements and shortfalls was given by Donald Sassoon 20 years ago:

Socialists not only played a crucial role in the establishment of the welfare system, but were the true heirs of the European Enlightenment, the champions of civil rights and democracy. They fought for the expansion of the suffrage when it was restricted. They fought for the rights of women more consistently and earlier than other parties. They fought against the entrenched rights and privileges of the old regime. They supported, often decisively, all the struggles against racial discrimination. They played a significant – and sometimes the major – role in the abolition of capital punishment, the legalisation of homosexuality and the decriminalisation of abortion.

Notwithstanding these successes, socialists neither abolished capitalism nor directed it through economic planning.

Donald Sassoon, One Hundred Years of Socialism: The West European Left in the Twentieth Century, London, Fontana, 1997, p 768

That seems a pretty fair summary, although it does raise the question of how much more successful socialism might have been had the movement not been handicapped by the Leninist baggage carried by many of its most dedicated and active advocates, baggage which probably alienated many more potential supporters than it attracted.

Since the time of Karl Marx, and particularly since the advent of Bolshevism, there have been many debates on the left about socialist economics – rather fewer on the politics of socialism.

One interpretation of Marxism went something like this: class is the crucial factor in any society. Political parties, where they exist, represent particular class interests. The interest of the working class – which is essentially identical throughout the globe – is represented by the (true) socialist party. Therefore, once that party is in power and beginning to ‘construct socialism’, all other political parties, movements or simple manifestations of dissent are illegitimate. Or, in more benign versions, they just fade away. Politics simply becomes redundant. In the Leninist version of post-1917 Russia, anyone attempting to pursue politics is an enemy of the people.

This hostility to politics predates Leninism. The assumption that the ‘Socialist Commonwealth’ would be some sort of harmonious, steady-state kind of society where all the conflicts of the past would disappear and well-being, happiness – and perhaps boredom – would reign supreme was widespread on the Left long before Lenin had been heard of.

Perhaps the best illustration of this is in William Morris’s celebrated News from Nowhere – sub-titled An Epoch of Rest. The chapter ‘Concerning Politics’ is very short. In the socialist future the time-travelling Morris asks his guide, Old Hammond, ‘How do you manage with politics?’

Said Hammond, smiling: ‘I am glad that it is of me that you ask that question; I do believe that anybody else would make you explain yourself, or try to do so, till you were sick of asking questions. Indeed, I believe I am the only man in England who would know what you mean; and since I know, I will answer your question briefly by saying that we are very well off as to politics – because we have none. If ever you make a book out of this conversation, put this in a chapter by itself, after the model of old Horrebow’s Snakes in Iceland.’

‘I will,’ said I.

Even before this we had the opening words of L’Internationale by the Communard Eugène Pottier proclaiming C’est la lutte finale with its implicit assumption that all struggle would come to an end with the overthrow of capitalism.

Fatal results

For most people, a common perception has been that no-one could be more ‘political’ than a socialist activist. That was true back in the late 19th century, as it is now, and at all times in between. Yet few people were actually so anti-political as many socialists, and in the 20th century this had literally fatal results.

This began when Lenin’s Bolsheviks played a major role in precipitating the civil war that followed the dissolution by the Bolsheviks of the Constituent Assembly and the suppression of all rival political parties. One of the first acts of the provisional government after the revolution of February/March 1917 had been to abolish the Okhrana, the Tsarist secret police. In December 1917 Lenin introduced the Bolshevik version, the Cheka, which was hardly an improvement.

Simple common sense suggested that if opponents of the new regime, however wrong-headed in their view, were denied any possibility of constitutional political action they would inevitably turn to violence, believing there was no alternative. This was quickly lost on many supporters of the Bolsheviks. In the following decades they lavished much righteous moral indignation on such evil people. Yet what did they realistically expect? Of course, fairly soon they ran out of real opponents and turned on each other.

But the rejection of ‘politics’ was not quite as simple as my account might suggest. Many on the Left, in the UK as well as elsewhere, were taken with what I have called – in Romancing the Revolution – ‘the myth of soviet democracy’. According to this myth, ‘bourgeois parliamentarism’, fleetingly represented in post-revolutionary Russia by the ill-fated Constituent Assembly, was replaced by the infinitely more genuine, more ‘real’, soviet democracy. This view drew on syndicalist beliefs in the superiority of workplace-based delegate democracy over rule by political representatives and the redundancy of political parties – except, in the Leninist version, the party of the working class.

Delegate democracy tends to be ‘activist democracy’ – which for some on the Left constitutes its great attraction. It usually works reasonably well in political parties where the ‘active’ are a high proportion of the membership, or in trade unions and other organisations where the – essential – issues at stake are usually drawn from a fairly narrow spectrum.

But, as the ILP’s Fred Jowett argued throughout the interwar period, this would leave the citizen even more remote from crucial decisions than the hugely flawed parliamentary system. He argued this even after the ILP’s disaffiliation from Labour when it was trying to pursue a ‘revolutionary policy’.

The belief that soviets, or something like them, were essential to ‘real democracy’ was to a lesser or greater extent widespread on the Left for decades. The control of delegates by shopfloor workers together with their right of recall was central to a belief in the reality of soviet democracy in Russia and hopes for its prospective replacement of parliamentarism in Britain.

Some advocates of soviet democracy, notably ‘Left Communists’ such as Sylvia Pankhurst in the UK and Herman Gorter and Anton Pannekoek in the Netherlands, were at least consistent in their anti-political stance. Their ideal may have been impracticable, but at least it was honest – as anyone who has read Pankhurst’s ‘A Constitution for British Soviets’ in The Workers’ Dreadnought of 19 June 1920 is likely to conclude – unlike the sleight of hand exercised by more ‘orthodox’ Leninists.

The consistent anti-political stance of the ‘Left Communists’ was apparent when the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) proposed that it should be represented on the councils of action set up to oppose intervention against the Bolsheviks in the war in Poland. Edgar Whitehead, national secretary of Pankhurst’s short-lived Communist Party (British Section of the Third International) objected. It was strike action that was being considered, he argued, and only those who were actually going to take part – workers in trade union branches and shop floor organisations – should be involved. There was no place for political parties such as the CPGB, or indeed his own organisation. Excluding political groupings was seen by the CP (BSTI) as essential in order to ‘sovietise the councils of action’. This at least demonstrated a certain consistency.

The view in the ILP

General support for Bolshevik Russia went way beyond the ranks of the small minority who joined Communist parties – or even, like many of the ILP’s ‘Left Wing’ in 1920, who seriously considered joining. There was a widespread view on the Left that while it was not what was needed here it was more or less OK, or better, in Russia.

Judging by the pages of the ILP’s Labour Leader, there was at first little criticism of Bolshevism in the ILP. In large measure this is explained by the common desire of both the ILP and Bolsheviks to see an end to the awful war as soon as possible, which the latter were actively pursuing. Even future firm anti-Communists such as Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden were slow to criticise, presumably for this reason.

In fact, the first real criticism of the Bolsheviks in Labour Leader appeared early in March 1918, nearly two months after the Bolsheviks’ dissolution of the Constituent Assembly. The prominent pacifist and later Labour MP, still celebrated in Bermondsey, Dr Alfred Salter, contested the Bolshevik regime’s democratic legitimacy, arguing that members of the ILP should ‘dissociate ourselves from its violence, its suppression of opposing criticism and its disregard for democracy’. He concluded that ‘Socialism apart from true democracy’ was ‘not only meaningless but valueless’.

He seems to have had little support in the ILP at this stage. Most, both within the ILP and throughout the rest of the Left, had invested far too much hope in the possibility of a socialist society actually being built in Russia to join Salter. They could attribute all criticism of Bolshevik Russia to the lies and distortions of the right-wing press – frequently only too happy to oblige with accounts of Communist outrages not noted for their accuracy. So great was the desire not to have one’s dearest hopes shattered that rose-tinted beliefs in the accomplishments of ‘soviet democracy’ persisted quite widely on the Left, not just for a few years but for decades.

Those who rejected Leninism early on had relatively little influence. Lenin, a master of invective, was able to dismiss Karl Kautsky as a ‘renegade’ so successfully that for many of us it is difficult to think of the man without the epithet coming unbidden into consciousness. Yet it is Kautsky rather than Lenin whose position has, I think, stood up better to the trials of the century since 1917.

It was not unreasonable one hundred years ago to have confidence that ‘wasteful’ markets could be replaced by planning and equality successfully pursued by public – in practice, state – ownership of all the main means of production, distribution and exchange. In the light of the experience of the last hundred years we cannot maintain such confidence in the traditional socialist nostrums during the 21st century. Bureaucratic nationalisation may be better, usually, than capitalist monopoly, but it is not an attractive alternative.

We must surely continue the difficult process of thinking what we mean by socialism in this century. We need, while maintaining our values, to be prepared to experiment, weigh evidence, consider practicality. After such an appalling year in 2016 even Ed Miliband’s ‘responsible capitalism’ may seem a distant hope and the late Alec Nove’s ‘feasible socialism’ much more of a dream than he would have wished. But if history has a lesson it is that things can and do change.

Salter was surely right about the indispensability of democracy and Kautsky was right about what our aims should be. As he put it in his much-maligned rejection of Lenin’s ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’:

The distinction is sometimes drawn between democracy and Socialism, that is the socialisation of the means of production, by saying that the latter is our goal, the object of our movement, while democracy is merely the means to this end…

Socialism as such is not our goal, which is the abolition of every kind of exploitation and oppression, be it directed against a class, a party, a sex, or a race…

Should it be proved to us that we are wrong and the emancipation of the proletariat and of mankind could be achieved solely on the basis of private property … then we would throw Socialism overboard… Socialism and democracy are not therefore distinguished by the one being the means and the other the end. Both are means to the same end.

Karl Kautsky, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat (1919. 1964 edition Anb Arbor, University of Michigan Press, pp 4-5.)

Today, it still seems as unlikely as it did to Kautsky that exploitation and oppression could be ended ‘solely on the basis of private property’. But what interpretation should we make of ‘solely’? What should ‘socialisation of the means of production’ mean in practice in the 21st century?

It is surely good that we are now more likely to support decentralisation and the virtues of operating on a small scale, which people find easier to identify with, than some huge bureaucracy. The ideas of the guild socialists, a version of which the ILP adopted in the 1920s, may have involved overly complex structures. Yet surely they were on the right track in trying to reconcile claims to a degree of control and influence over economic enterprises by workers, consumers and citizens?

It is good that we are now discussing the possibilities of a basic universal income. But should we not as a matter of urgency – given the threat to so many jobs from automation – ensure that anyone whose work is made redundant by technological advance is guaranteed both their previous income and the widest range of possibilities for retraining and education?

Much that I would now support may well turn out to be undesirable or impracticable, or both. We have to be open to such possibilities and avoid getting bogged down in dogmatism.

One thing we can be pretty sure of is that the ‘lessons’ of 20th century Leninism are predominantly negative. In Russia, 1917 began very well and ended badly.

—-

Ian Bullock writes about the relationship between socialism and democracy.

He is the author of Romancing the Revolution: The Myth of Soviet Democracy and the British Left, and co-author, with Logie Barrow, of Democratic Ideas and the British Labour Movement, 1880-1914. He also edited Sylvia Pankhurst: From Artist to Anti-Fascist with Richard Pankhurst.

Under Siege: The Independent Labour Party in Interwar Britain, by Ian Bullock, will be published by Athabasca University Press later in 2017.

Also see Ian Bullock’s ‘What Can We Learn from the Inter-War ILP?’, plus ‘A Living Wage: A Policy with History’, ‘Disaffiliation and its Aftermath’ and ‘Corbyn: Labour’s Accidental Leader’.

His profile of Fred Jowett is here.

20 March 2018

But the USSR was strangled since its inception. We sent troops in an attempt to kill the revolution in its embryonic stage. This resulted in war socialism and only opened the road to Stalin.

29 June 2017

I’m glad that Ernie and I seem to be agreed about so much. I totally concur with him about what he rightly calls “past follies”. But I don’t know how the EU got into the act – I don’t think I mentioned it even indirectly in the piece on ‘lessons’ of 1917. I could go on for many pages about why I believe he is wrong to be hostile towards – as distinct from critical about – the EU but I’ll confine myself to making just one point.

In 1914 socialists in Britain, as elsewhere, were divided by the outbreak of war. None of them wanted a war, or thought that it was anything less than a terrible disaster. But some believed that it was necessary to defend Belgium and France from the unwarranted invasion of the German armies and to take a stance against what they called ‘Prussian militarism’. Others – including most of the ILP, though not all ILPers – were firmly opposed. The exception that springs to mind is Clement Attlee who, falling out with his brother, another ILP member, on the issue, joined up, was badly wounded and ended the war with the rank of major.

But however fundamentally they disagreed about the crucial question of the war there was something very close to unanimity that one of the objectives to be worked for, along with a just peace, was the ‘United States of Europe’. For example, as early as 20 August 1914, just over a fortnight after Britain’s declaration of war, the ILP’s weekly Labour Leader looked forward to “the scheming Chancelleries of Europe” replaced by “a permanent federation of interdependent states”. The following month Fenner Brockway published two articles under the title ‘After the War – What?’ the second of which set the objective ‘Towards a United States of Europe’. Typically for Brockway this was just the start of a much wider unity. Beyond a Europe with a European Parliament and a European police force, he caught a glimpse of “a federation of nations in which America and the British Dominions are part, and, more dimly, of a still larger federation including the peoples of Asia, Africa and South America”.

I’m as sure as one can be that those who called for a United States of Europe in 1914 would not be overly impressed by the EU as it is at present. Probably they would not even give it Jeremy Corbyn’s famous seven out of ten. But I’m equally sure that they would have seen it as a necessary and promising step in the right direction. I certainly would not want to turn my back on their aspirations.

19 January 2017

Really interesting paper by Ian Bullock, especially when he suggests we define more clearly what we mean by democracy and socialism. While few would now agree that Soviet-style systems have anything to teach us about democracy, equality and the good life, neither does neoliberalism, so beloved by the Blairite (establishment) and the trickle-down wing of the Labour Party. And while some of us may have differing perspectives on policy issues it puzzles me beyond belief how anyone calling themselves socialist or left social democrats can support a European Union which is capitalism writ large with the C word embedded in the treaty of Rome and reinforced in every EU treaty since. How any socialist can support that abomination is beyond me.

On the issue of automation and redundant workers, I’m 100% in agreement with Ian when he advocates a basic universal income and good quality education and training programmes for all who lose their jobs. But if a future Corbyn government is not to repeat past follies and waste billions (hundreds of billions) on cheap and useless welfare to work programmes, a legacy of both Labour and Tory administrations who simply hadn’t a clue, it must exclude the private sector, which is good on marketing spin but crap on delivering promises, really good at enriching itself on the backs of the unemployed while delivering little, apart from a lot of noise and widespread disillusionment among unemployed beneficiaries.