East Anglia is hardly known as a bedrock of the early ILP. But as MIKE WADSWORTH illustrates in his portrait of the Great Yarmouth branch before the First World War, local ILPers were as committed and passionate in their socialism as any of the organisation’s more famous figures.

For many people, when you mention the Independent Labour Party (ILP), they will talk about its foundation in Bradford, its growth in Yorkshire and Lancashire, the Clydeside MPs, James Maxton and John Wheatley, and the decline in its fortunes following its disaffiliation from the Labour Party in 1932.

But the early ILP extended far more widely across the country, and far more deeply into British society, than those few well-known facts and famous figures suggest.

But the early ILP extended far more widely across the country, and far more deeply into British society, than those few well-known facts and famous figures suggest.

Take East Anglia, for example, a region hardly remembered as a bedrock of ILP influence and activity. Yet, when the Great Yarmouth ILP was set up in 1906, there were already branches in Norwich, Ipswich, Lowestoft and a few other places across the area.

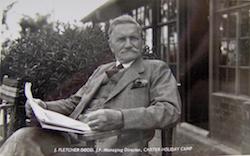

The intention to set up an ILP branch was announced at an open-air meeting held on the town’s Brewery Plain on 18 August 1906, when the speakers included GH Roberts, the ILP’s MP for Norwich, and John Fletcher Dodd, who was to play a major role in the growth of Great Yarmouth ILP over the next two decades.

The meeting attracted what was described in the local paper as “a fair-sized crowd”. The organisers stated they had come to plant the red flag in Great Yarmouth, arguing that the working class were no more than 14 days from the workhouse, and their interests were not served by either the Conservative or Liberal parties.

The speakers stressed that ILPers were not atheists, that many members were inspired by the Bible as well as by the writings of John Bunyan, Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin, and that they did not believe in revolution, but “an evolution of the race to a higher state of life”.

The ILP was a socialist organisation whose objectives included, they said: “Full political rights for every man and woman; the provision of work for all capable applicants; state pensions for the aged; full free secular moral education with free maintenance while at school or university; municipalisation and public control of the drink traffic and of hospitals and infirmaries; abolition of indirect taxation and the gradual transference of all public burdens onto unearned incomes with a view to their extinction; the nationalisation and public use of the land, mines, railways and canals.”

The ILP was a socialist organisation whose objectives included, they said: “Full political rights for every man and woman; the provision of work for all capable applicants; state pensions for the aged; full free secular moral education with free maintenance while at school or university; municipalisation and public control of the drink traffic and of hospitals and infirmaries; abolition of indirect taxation and the gradual transference of all public burdens onto unearned incomes with a view to their extinction; the nationalisation and public use of the land, mines, railways and canals.”

Speakers at Brewer Plain said the socialist movement aimed to provide ordinary people with enough food to eat, good clothes to wear, houses to live in and “reasonable opportunities” in education and recreation. The objective was not political power for the sake of it, but to ensure the state was used to “up lift” the whole of the working class so that all could lead a decent life.

Foundation

The branch was formally founded at the Unitarian school room during a conference that also established an ILP federation for the eastern counties, a body replaced in 1909 by a Divisional Council, by which time there were branches in Norwich, Lynn, Yarmouth, Lowestoft, Ipswich, Halstead, Braintree, Hitchin, Romford, and a few other towns.

Fletcher-Dodd (left) was one of the founding members of the Great Yarmouth branch. In 1906 he had set up a Socialist Camp at Caister-on-Sea, a forerunner of many other holiday camps that later became a feature of that part of the Norfolk coast. [1]

Fletcher-Dodd (left) was one of the founding members of the Great Yarmouth branch. In 1906 he had set up a Socialist Camp at Caister-on-Sea, a forerunner of many other holiday camps that later became a feature of that part of the Norfolk coast. [1]

Fletcher Dodd believed socialism was the modern interpretation of Christ’s teachings and ILP members in Great Yarmouth were urged to promote socialism within the borough with “religious zeal”.

The ILP’s ideas were further expanded at a meeting in spring 1908 about ‘The future of Liberalism’ when the Liberal Party was portrayed as a spent force that had lost the support of the working classes and become the third party of British politics. It was accused of failing to live up to its promises of change, while the socialist movement would see those changes to their conclusion.

For the ILP, the root cause of poverty was private ownership of the means and infrastructure of production. What was needed were not small measures of reform but total social reconstruction in which wealth and new technology were used to raise the standard of living of all.

The ILP’s economic thinking at the time was influenced by JA Hobson, whose ideas of under-consumption were expanded in the 1920s.[2] But for the ILP, socialism always had a moral and ethical basis as well as an economic one.

One of the national figures who visited the Great Yarmouth ILP during the period was Arthur Henderson who debated with the Liberals in 1911, arguing that the main cause for poverty was private ownership of land and private control of industry for profit. He also said the ILP was not trying to set up some form of utopia divorced from the real world, but saw socialism as a way of organising society on a “scientific basis”, not some “quack remedy”.

The branch did not immediately stand candidates in borough council elections or for the other locally elected bodies, but in 1906 it did send a list of questions to candidates in the municipal elections. In effect, these called for the municipalisation of milk, water and gas; for municipal lodging houses; for more active use by the council of the Unemployed Workman Act; and for the abolition of contracts granted to outside bodies by the council. Neither the Liberal Party nor other ‘progressive’ candidates bothered to reply.

Permanent home

By early 1909 the branch had a permanent home attached to the Old Meeting House in Middlegate Street, which is now the Unitarian Church. This clubhouse, the branch stated, was not to be a drinking den, but a place for learning and for “making socialists”.

A major ILP concern at the time was women’s suffrage and a campaign was organised in Great Yarmouth that culminated in a large meeting at the Town Hall where the main speaker was Charlotte Despard, who argued that socialists who did not believe in universal suffrage were not being true to the socialist message. Those advocating the extension of suffrage to women were fighting for justice for both men and women, she said.

A major ILP concern at the time was women’s suffrage and a campaign was organised in Great Yarmouth that culminated in a large meeting at the Town Hall where the main speaker was Charlotte Despard, who argued that socialists who did not believe in universal suffrage were not being true to the socialist message. Those advocating the extension of suffrage to women were fighting for justice for both men and women, she said.

Among the other national leaders to appear at other well-attended ILP public meetings were Phillip Snowden and George Lansbury (pictured), the latter arguing that one day Great Yarmouth would have a Labour MP.

The local ILP also worked closely with Great Yarmouth Trades Labour Council, a fellow affiliate to the local Labour Party, and their public meetings drew attention to unemployment. The ILP called on the borough council to provide work for the unemployed and to use existing legislation to provide free school meals for needy children. Some Liberal voters, calling themselves ‘progressives’, lamented that such campaigning work was left to the newly formed ILP, while other progressives did nothing.

The ILP did eventually stand candidates in local elections, although not always with much success. Fletcher Dodd stood in the 1910 and 1913 county council elections, for example, but lost heavily to the Conservative candidate both times.

He was more successful in 1911 when elected unopposed to the Flegg Rural District Council. One of the four councillors representing Caister, he was the only socialist on the council but was appointed to the Housing and Town Planning Committee, the Caister Sewerage and Drainage Committee, and was on the Board of Guardians of the local Poor Law Union.

The years between 1910 and the start of the First World War saw an increase in strikes across the whole of the UK. In Great Yarmouth meetings were held in support of the 1912 miners’ strike which Fletcher Dodd called the major issue of the day, adding that it was a glorious example of workers standing together for improved working conditions, and that the only way to resolve problems facing the coal industry was nationalisation.

At later meetings, the ILP argued that nationalisation of the sources of wealth and of national industries would lead to a “co-operative commonwealth”. It also stood for a minimum wage for all industries,[3] a universal eight-hour working day,[4] a Right to Work Act, improvements to the education system and housing, and the abolition of the Poor Law.

During the years leading up to the First World War, the ILP continued to hold meetings in support of the trade union movement, Irish Home Rule, and in support of Tom Mann and others when they were charged over the ‘Don’t Shoot’ leaflet.[5]

World War One

The First World War began in 1914 and, like the rest of Britain, Yarmouth was preoccupied with what was happening across the country before the start of the conflict. Once war began, it became the pre-eminent topic especially as it affected the town’s major industries – tourism, fishing and agriculture.

Great Yarmouth ILP joined the ILP nationally in opposing the war and held meetings in the Market Place, initially with some support. Similar anti-war meetings were held in other towns, such as Norwich where war was described as a relic of barbarism.

However, support for socialist internationalism was soon overtaken by popular backing for the war, both within Great Yarmouth and across Britain. In fact, members of the Norwich Co-operative Society and the local branch of the Sailors and Firemen’s Union[6] were active participants in a torch-lit parade through the town in support of British involvement.

So what can be learned from the early years of the ILP in Great Yarmouth?

Certainly, it was not influential within local political structures, unlike in other larger towns and cities within East Anglia. And its stance on many issues, such as opposition to the First World War, was not widely reflected among many who lived in Great Yarmouth.

Yet, it did have a measure of support when it campaigned against issues such as unemployment, bad housing and in support of free school meals for children from poor backgrounds.

The approach of the local ILP closely reflected the ethical socialism of the national organisation, as members expressed support for reforms and rejected the crude economic determinism of the Social Democratic Federation.

The belief that socialism in Britain owed as much to Methodism as to Marxism was also reflected locally, especially in the language used by figures such as founder John Fletcher Dodd, who was influenced by Non-Conformist Christianity and talked about bringing Christ’s teachings into reality.

The Great Yarmouth ILP branch was enthusiastic about ‘making socialists’, a zeal shared by ILPers across the country, and had a passionate desire to improve the lives of ordinary people.

Looking back from our somewhat more cynical times, their ideals may seem naively expressed and articulated, but they were ideals that were genuinely held.

—-

This is an edited version of a longer article originally published in 2006 in Yarmouth Archaeology, the journal of the Great Yarmouth Local History & Archaeological Society, to mark the centenary of the founding of the Great Yarmouth branch of the ILP.

Sources

Eastern Daily Press – 1906 to 1914

Great Yarmouth Mercury – 1908 to 1912

Yarmouth Independent – 1906 to 1914

The ILP Past Present, by Barry Winter, Independent Labour Publications, 1993

Notes

[1] During 1908 this ‘Socialist Camp’ was reported to be attracting many visitors and Fletcher Dodd was congratulated on turning what was considered a piece of wasteland into an attractive place to visit.

[2] JA Hobson was a radical liberal whose ideas were to form the basis of the ILP’s ‘Socialism in Our Time’ programme of the mid-1920s. Hobson’s ideas about imperialism were taken on by Lenin prior to the First World War and were the basis of Lenin’s ‘Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism’.

[3] It was suggested that the minimum wage should be set at thirty shillings a week.

[4] The ILP argued that overtime should not be allowed whilst there were high levels of unemployment and that if the work in hand could not be done in normal time, then extra staff should be recruited.

[5] Fred Bower, a syndicalist, had written an appeal to soldiers not to shoot strikers. This was first published in The Irish Worker and then in The Syndicalist with which Mann was associated. The article was then published as a leaflet by Fred Crawley and distributed to soldiers based at Aldershot. Crawley, the editor and the printers of The Syndicalist were arrested and were prosecuted and imprisoned. Mann spoke at a meeting in Salford and elsewhere in support of those who published the article and was himself arrested and charged with incitement to mutiny under the 1797 Mutiny Act.

[6] In October 1914, the local Liberal Association adopted J. Havelock-Wilson, then president of the National Sailors and Firemen’s Union, as the ‘Lib-Lab’ candidate for Great Yarmouth at the general election due to be called that year. Havelock-Wilson was one of the union leaders who spoke in favour of Britain being involved in the war at the ‘patriotic’ demonstration that took place in Great Yarmouth in September 1914. He was also fiercely anti-socialist, opposed to groups such as the ILP and to the leaders of the Russian Revolution.

19 May 2020

Thank you, Mike. A very interesting read. My and others’ research in Northampton reveals a very similar picture – the belief in social ownership and the influence of Christianity on ethical socialism. Here too the ILP was actively pacifist in WW1. In Northampton the BSP was stronger than the ILP, and longer established. It shared those beliefs and influences, but not the pacifism. Both parties co-operated with the trades council to create Northampton Labour Party in 1916.

8 May 2020

This is a fascinating account of the political roles played by ILPers in Great Yarmouth in the party’s early years. Mike’s research in uncovering this is splended.