WILL BROWN reviews a fascinating and timely examination of the sources of anticolonial opinion in Britain, one that reinforces the importance of new and more honest accounts of black history and Britain’s imperial past.

At a time of renewed calls to rediscover and publicise black history, Priyamvada Gopal’s Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial resistance and British dissent provides a fascinating and timely examination of the sources of anticolonial opinion in Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries. In doing so Gopal highlights the role of Trinidadian-born George Padmore in shaping the ILP’s own political stance on empire.

Gopal’s purpose is to challenge established histories of the end of colonialism which often portray it as a benevolent gift from an enlightened liberal metropole to a grateful commonwealth. Such histories, Gopal argues, show colonised peoples initially as victims, and later grateful recipients of British benevolence, lacking any political agency of their own.

Gopal’s purpose is to challenge established histories of the end of colonialism which often portray it as a benevolent gift from an enlightened liberal metropole to a grateful commonwealth. Such histories, Gopal argues, show colonised peoples initially as victims, and later grateful recipients of British benevolence, lacking any political agency of their own.

In contrast, Gopal argues that the gradual growth of anticolonial sentiment in Britain developed as a result of, and in response to, the struggles of colonised people themselves and the activists from the colonies who took their campaigns to the imperial capital itself.

Selecting a series of anticolonial revolts and key figureheads of anticolonial resistance, Gopal traces a century of opposition. Two key mechanisms feature in Gopal’s history.

First, she highlights how revolts in the colonies, and the injustices that prompted them, led to enquiries into, and criticism of, imperial practice in parliament and the British press. From the 1857 Indian uprising, through rebellions in Jamaica in 1865, to the wave of strikes and protests in the Caribbean and West Africa in the 1930s, and the ‘Mau Mau’ rebellion in Kenya, Gopal shows how political revolt in the colonies changed the terms of political debate in London.

The established view of a benign and civilising imperial power came under increasing scrutiny. By causing debate and self-reflection in the metropole, Gopal argues, rebellions “formed the seedbed for oppositional discourse on imperial questions to emerge”.

Secondly, Gopal focuses on how political leaders, activists and writers from the colonies took their campaigns to Britain and led the political organisation of anticolonial sentiment. These activists, engaged in a “reverse pedagogy” – those who were supposed to be the recipients of enlightened colonial teaching and civilisation had lessons of their own to teach the British political establishment.

Comrade Sak

Key figures included Bombay-born Shapurji Dorabji Saklatvala, who after moving to Britain in 1905 joined the ILP, later to leave along with other members of the ‘left wing group’ to join the Communist Party in 1921. He was elected as a Communist MP for Battersea North in 1922 with the initial backing of the Labour Party and used his position in parliament to rail against the injustices of the Raj.

‘Comrade Sak’ (pictured left) as he became known, declared as “humbug” the idea that one country can hold another in subjugation and then offer reform and partnership: “There are not two ways of ruling another nation. There is not a democratic way, and also an unsympathetic way.”

‘Comrade Sak’ (pictured left) as he became known, declared as “humbug” the idea that one country can hold another in subjugation and then offer reform and partnership: “There are not two ways of ruling another nation. There is not a democratic way, and also an unsympathetic way.”

Over 500 interventions in the House earned him the title of the ‘member for India’ and marked him out from wider CPGB indifference to questions of race and empire. Indeed, he later criticised the party for treating colonial issues “as a mere aside”.

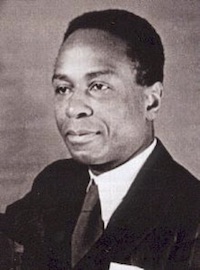

Gopal also highlights the key role of George Padmore in shaping left-wing politics in the 1930s. Padmore was born in Trinidad and became a communist after moving to the US. He split with communism in the 1930s over the Soviet Union’s tacit approval of British and French imperialism. Pursuing his alliance with Britain and France, Stalin’s tortuous line was that ‘democratic imperialism’ was less objectionable than the ‘fascist imperialism’ of Germany and Italy.

Padmore had no time for such obfuscations. Having moved to London he became a central figure in a fertile period of growing anticolonial writing and activism in the capital, one that included figures such as CLR James, Saklatvala, Claude Mackay and British radicals such as Sylvia Pankhurst and Nancy Cunard. They brought an “uncompromising rejection of gradualism and tutelage” and insisted on self-representation and self-emancipation.

These black and Asian anticolonial intellectuals and campaigners formed “an active nodal link between resistance in the colonies and metropolitan dissidence” and engaged with “both Marxism and nationalism”.

They also helped found the organisations that emerged to further the campaign against colonialism. The League Against Imperialism was launched in 1927 at a conference attended by more than 130 organisations from 37 countries. The ILP’s James Maxton was elected as chairman with Fenner Brockway chairing the British section of the League.

The International African Service Bureau (IASB), founded in 1937 by Padmore, James and others, emerged out of the campaign against Italian intervention in Ethiopia and launched the periodical International African Opinion. Padmore was also central in organising the Pan African Congress, held in Manchester in 1945. Attended by more than 200 delegates, it shaped much of the post-war anticolonial agenda.

Padmore & the ILP

Padmore’s influence was particularly evident in the ILP. At the turn of the century, left wing opposition to imperial expansion was balanced by a view that Britain should improve rather than dispense with its existing imperial possessions. ILP figures, including Keir Hardie, and later Fenner Brockway, had themselves visited India and made increasingly strident criticisms of British rule.

After returning from his tour of India in 1908 where, Gopal argues, he and other Labour figures were deeply influenced by nationalist activists, Hardie declared: “My sympathies were always with India, but now they have grown a hundredfold.” For “daring to tell the truth about India”, Hardie received what the Indian philosopher and nationalist Aurobindho Ghose called a “hideous, indecent and savage reception” by the English press.

After returning from his tour of India in 1908 where, Gopal argues, he and other Labour figures were deeply influenced by nationalist activists, Hardie declared: “My sympathies were always with India, but now they have grown a hundredfold.” For “daring to tell the truth about India”, Hardie received what the Indian philosopher and nationalist Aurobindho Ghose called a “hideous, indecent and savage reception” by the English press.

Yet even in the inter-war years, many, including the Labour Party, stopped short of supporting colonial independence in Africa, preferring instead to argue for a more paternalistic view in favour of supporting the social and economic development of the colonies. Even after the Second World War, the dominant view, including that of the Attlee government, was that Africa was not ‘ready’ for independence.

The arrival of Padmore (pictured above) as a frequent contributor to the New Leader in the late 1930s massively increased the ILP’s coverage of colonial issues to become the main British weekly to carry articles – “bolder and sharply more critical” – on the colonial situation. According to Gopal, the ILP became a key route by which anticolonial discourse percolated through to a wider public audience and to parliamentary debate.

In the New Leader, Padmore urged British workers to see colonial peoples as allies not competitors and made trenchant criticisms of the Labour Party’s stance. It was a view that influenced ILP figures such as Brockway, John McGovern and George Orwell and their arguments that the fight against fascism could not then leave in place the vast injustices of the empire.

By 1941 the ILP had passed a resolution in favour of “social justice in Britain and national liberation in the empire”. And by drawing parallels between the oppression of colonial subjects and the exploitation of the working classes in the UK, Padmore, James and others moved critics of empire from a position of paternalistic sympathy towards one of solidarity and internationalism.

In conclusion, Gopal notes how anticolonialism in Britain emerged against a “tenacious colonial mythology”. She notes how “calls for reform … in the colonies were generally responses to pressures from below rather than initiatives from above”, and that in doing so they changed the very understanding of words like “liberty, freedom and self-determination”.

In this exceptional history, Gopal’s analysis of the role of black and Asian revolts, activists and intellectuals reinforces the contemporary importance of a new and more honest account of Britain’s imperial past.

—-

Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial resistance and British dissent by Priyamvada Gopal was published by Verso in 2019 and available here for £10.49.