GARY KENT reflects on the 100th anniversary of partition on 3 May and the distorted thinking that for decades dominated left-wing approaches to the province, the Troubles and the sectarian divide.

Politics can sometimes get things so dramatically wrong that it takes decades to realise and rectify. Poor analysis takes root and impedes the often healthy process whereby minorities can become majorities and throw off the shackles of outdated thinking and alliances. WB Yeats’s classic lines about ‘the worst being full of passionate intensity while the best lack all conviction’ live on in so many ways.

Those words were particularly apt for a time and a place where the competing demands of minorities and majorities had lethal consequences for many decades – Ireland and Northern Ireland, whose partition came into force 100 years ago.

Those words were particularly apt for a time and a place where the competing demands of minorities and majorities had lethal consequences for many decades – Ireland and Northern Ireland, whose partition came into force 100 years ago.

For much of the last century, British and Irish left-wing attitudes were dominated by different forms of anti-partitionism. The border was seen as an imperialist injustice, which distorted the development of a politics that could have united Protestants, Catholics and Dissenters, as Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen of the late 18th century put it.

There were dissenting voices from the very beginning to the accepted left-wing view. The ILP paper, Labour Leader, ran a front page story at the time that accepted partition and described as rock-like the reality of Ulster. By the 1990s the ILP had developed a revisionist account of partition and criticised the ‘junior James Connolly’ version of history peddled by so much of the left.

Yes, it is true the province of Ulster was historically composed of nine counties and three were left out by partition to be part of the new Irish state because their incorporation into Northern Ireland would have put Protestants in a minority.

Yes, it is true that many Protestants were descended from settlers and many Catholics were evicted from their land, left to carry their resentment for decades, or longer. My late friend, Sean O’Callaghan, a senior member of the IRA from the 1970s, once told me of a time when he and a fellow volunteer were aiming their rifles from the top of a hill in, I think, Fermanagh. His comrade pointed out a distant farm and said it belonged to his family … 400 years previously.

Yet, time changes everything. And in 1921 Protestants were clearly opposed to being part of the new Irish state. Their wishes were reluctantly accepted by Irish representatives in negotiations with British prime minister David Lloyd George. Chief among them was Michael Collins, a military genius who had done much to weaken the British machine by carrying out assassinations, earning himself the sobriquet ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’.

Collins argued that the “incomplete settlement” gave the Irish the freedom to achieve freedom. In other words, the Irish state could be expanded at a later date. That may well still happen, of course, but it will be through very different means than those sought for decades – the forcible incorporation of Northern Ireland under duress.

Fresh words

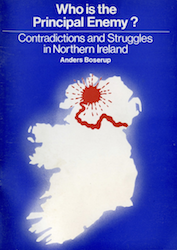

Another figure whose analysis stands the test of time is the young Danish sociologist, Anders Boserup whose pamphlet, Who is the Principal Enemy? – contradictions and struggles in Northern Ireland, was published by the ILP and appeared in Socialist Register in 1972.

It was written in August 1971, shortly before internment and the escalation of the Troubles, which endured until the mid-1990s and whose effects are still being felt today. Such an enduring, if somewhat dense analysis, clearly based on Marxism, was a great achievement for a man of just 21.

It was written in August 1971, shortly before internment and the escalation of the Troubles, which endured until the mid-1990s and whose effects are still being felt today. Such an enduring, if somewhat dense analysis, clearly based on Marxism, was a great achievement for a man of just 21.

His words still sound fresh and informed. He rattles through a sketch of Irish history, outlining how the two parts of the island of Ireland were shaped by different economies and the alliances that flowed from them, including a masterful assessment of the cross-class bloc around the Orange Order.

It’s vital to remember just how isolated and frustrated he must have felt as the rest of the left adopted a simple-minded anti-partitionism. It’s interesting that the editors of Socialist Register, Ralph Miliband and John Saville, put a hefty health warning over the essay in their introduction. No-one ever answered his points, although he fundamentally challenges the theory and praxis of their key writers who, to one degree or another, believed that the good guys were those who wanted to impose Irish unity, and the bad guys were those who feared this would be calamitous in the circumstances.

Boserup writes: “The strategy of ‘national liberation’, which the left is presently pursuing, is based on a faulty analysis and leads absolutely nowhere. It portrays the windmills of British imperialism as a mighty army and overlooks the real enemy. In so doing, far from enriching the revolutionary experience of the working class and preparing the ground for the more meaningful struggles of the future, it is trapping the working class ever more firmly in its sectarian ideologies. Suitably romanticised, the bloody and pointless battles of these years will probably one day take their place alongside the trophies of 1690 and 1916 to fulfil their only possible role: to cripple the consciousness of future generations in Ireland.”

It’s entirely possible, however, that these forces could have been marginalised earlier if more people on the left, chiefly in Ireland but also in Britain, had been able or willing to understand that there were two nations, rather than one that had been deprived of unity.

Boserup is clear in this analysis: “From every point of view, save those of territoriality and statehood, the Protestants and Catholics in Ireland constitute two distinct national groups. These are usually described as Catholic and Protestant but the difference between them is not only, not even primarily religious. It is two entirely different cultures with little in common apart from language. True, one finds among both Protestants and Catholics a feeling of ‘Irishness’, but the similarity stops at the label. Behind it one finds national mythologies, conceptions of Irish history and Irish destiny, and social and political ideologies which have virtually nothing in common.”

Squeezed view

At the beginning of the Troubles, however, those who sought to find common ground between Protestant and Catholic workers were ruthlessly squeezed out of the equation by those who believed, in Boserup’s words, that “British domination is … the root of all the problems of Ireland. In the socialist ideology, British domination becomes British imperialism. In this way everything fits nicely into place in what appears to be a consistent socialist theory. The severing of the links with the British oppressor becomes the precondition for socialism in Ireland.”

It was poppycock, and Boserup was able to identify how to overcome it. He writes: “If it is to engage effectively in the struggle against the Orange system the left must necessarily dissociate itself from 32-county nationalism and accept the existence of the Northern state. As long as the left does not do this but, more or less wholeheartedly, plays the tune of Catholic nationalism, it is in fact shoring up that system by providing it with a badly needed scarecrow to frighten Protestant workers.”

His clear-headedness is also apparent when he writes: “The affirmation that Northern Irish Protestants constitute a separate national entity with a right to refuse incorporation in the Republic is usually considered to be divisive of the working class and therefore anti-socialist. On the contrary, I think it is the stubborn affirmation of unity and solidarity where none exists, and the extravagant claim of Irish Catholics to the whole island which is divisive.”

He pulls no punches in analysing the advocates of unity without consent: “The Catholic left demands a 32-county republic and tries to sweeten the pill for Protestants by affirming that this will be a socialist and ipso facto a secular republic. Protestants would be fools if they believed it. Socialism in Ireland is not for tomorrow and, even if it were, deeply entrenched ideologies do not disappear overnight. The Catholic left, by its espousal of the demand for a united Ireland, has demonstrated that even those who claim to constitute the socialist vanguard are trapped in nationalist ideologies.”

He adds: “Ultimately, it is to put the cart before the horse to demand a 32-county republic and hope that it can then develop towards socialism. There is no surer way of perpetuating religious divisions than to impose Irish unity against the will of almost a quarter of its population, and a state so created would be socialist, if at all, only in name.”

He could see that the Provisional IRA depended on its support in Britain and abroad for its aim of forcible reunification. His final sentence is a warning lost in the rush to misunderstand and marginalise Protestants and adopt an unbalanced perspective on a complex issue: “It is therefore important that British and other socialists should realise that in responding to the call for ‘solidarity in the struggle against British imperialism’ they are in effect betraying socialist ideals and backing policies of national oppression of the Protestant minority in Ireland.”

Softened edges

The truly historic achievement of the Good Friday Agreement, more than 20 years later, was to find a way to secure wide support for the legitimacy of Northern Ireland and for the principle of consent – in short, for the idea that the people of Northern Ireland would determine their own fate. The sharp edges of partition were softened so those who valued their British identity or their Irish identity, or who favoured a more distinct Northern Irish identity, could all live together.

Yet, as recent events have demonstrated, Northern Ireland remains scarred by sectarianism and fear. I haven’t been to ‘forgotten’ Protestant West Belfast for many years, but it has long been a place of appalling low educational attainment and poverty.

Yet, as recent events have demonstrated, Northern Ireland remains scarred by sectarianism and fear. I haven’t been to ‘forgotten’ Protestant West Belfast for many years, but it has long been a place of appalling low educational attainment and poverty.

Many loyalist working class people fear they will be further marginalised and hate the way Sinn Fein recently thumbed its nose at Covid regulations by holding a socially undistanced funeral for the Provo intelligence chief, Bobby Storey. They fear the Brexit protocol is breaking links with Great Britain. And they are not entirely wrong, even if the lumpen means some of them use to express their anger is appalling.

As so often, the British state has sleepwalked into another fine mess. Successive governments throughout the 20th century turned a blind eye to discrimination against both Catholics and poorer Protestants, and failed to seriously consider the simmering socio-economic problems of Northern Ireland until they exploded in the late 1960s. The British and Irish states eventually cottoned on and defeated terrorism but the raw and root causes of disaffection and alienation remain, especially in unionist communities.

One political leader worth heeding is Proinsias de Rossa, a veteran left-winger who took part in the IRA’s border campaign from 1958 to 1962. He was interned, became parliamentary leader of the Workers’ Party, which grew out of the Official IRA and then split to become the Democratic Left before merging with the Irish Labour Party. De Rossa was at one time Ireland’s ‘minister for fish and ships’ and I remember interviewing him in his speeding ministerial car between Dublin and Meath in 1996.

He recently wrote a letter to the Irish Times posing a fundamental question: “Why is a united Ireland necessary?” He rounds on the “truism” of a united Ireland. “It is a common part of our public discourse in the Republic of Ireland to say one agrees with, wants, or supports the idea of a ‘united Ireland’,” he writes. “But why? Why is this necessary? Why does virtually everyone in public life and those who write editorials for the Irish Times feel the need to support it and even describe it as ‘a noble aspiration’?”

He argues it is time to reframe the national story “to reflect current political and constitutional realities so that our primary schoolchildren no longer carry this 19th century intellectual baggage which delivers some of them as recruits to the irredentists”.

Instead, he says, “community reconciliation in Northern Ireland is the urgent task we should be engaging with as a ‘noble aspiration’” because the Belfast Agreement “embedded a constitutional settlement for peace on this island fit to last for the next 100 years and more. But only if the political leadership in Northern Ireland, Westminster and the Oireachtas [Irish Parliament] harness it to the task of reconciliation rather than trying to outflank each other.”

It may well be that recalcitrant loyalists and unionists, the latter not all Protestant, can be overcome in a 50 per cent plus one border poll. Partition in 1921 reflected a pre-existing reality that remains. But I am not convinced the Irish state could easily absorb Northern Ireland given all the intensely practical and difficult issues, such as how health services could be aligned, and how the Irish state would cope with the cost of Northern Ireland’s Troubles-related social costs, the higher welfare payments needed to cope with all the physical and psychological damage.

We need a British left that works with Irish left-wingers like de Rossa and has learnt the lessons of a century of failure. We need a Labour government as a matter of urgency to lift working class conditions on both sides of the sectarian divide and encourage conciliation, especially through integrated education. We need to be very careful what we wish for.

—-

See also: ‘Building a New Consensus’ by Gary Kent.

25 May 2021

I am very grateful to Gary for his overview of the recent past in Northern Ireland, including his reference to the work of Anders Boserup, and would add two comments. The first is about understanding the scale of the political violence inflicted by the state and by the paramilitary organisations of both sides.

Since the mid-1960s some 3,557 have died in the province as a direct result of this violence and if the same had happened in Great Britain the equivalent figure would be around 140,000 deaths. Physical injury has been suffered by at least another 30,000 and the equivalent number for this is around 1.2 million. Then there are the countless numbers whose mental health has suffered as a result of the troubles, a huge issue in Northern Ireland.

If you then consider the geographical concentration of much of the violence, in certain areas of north Belfast for instance, then perhaps we can begin to get a small insight into the trauma suffered by so many. The human cost to people on all sides of the argument has been horrendous.

That is why maintaining and developing the 1998 Peace Agreement is so important – who would want to return to the days of relentless violence? And yet the peace process, which of necessity had to institutionalise sectarian difference, has an increasingly fragile existence.

Although Boris Johnson leads the Conservative and Unionist Party, his blatantly duplicitous behaviour in relation to the post-Brexit trading arrangements showed little understanding or concern for the dynamics of Irish politics. That the Democratic Unionists swallowed his initial promise of no border in the Irish Sea was a product not just of their own enthusiasm for Brexit but also their breath-taking naivety.

It is a sad and ironic reality that a resurgent British nationalism in the Conservative Party makes the wellbeing of Northern Ireland an ever more peripheral concern for people like Johnson, with potentially very damaging consequences.

Co-operating with the Workers’ Party and others opposed to sectarianism in the 1980s and ’90s, the ILP worked hard to raise the level of political debate about Northern Ireland within the Labour Party. Perhaps we need to do so again.

1 May 2021

On Northern Ireland I feel that the Brexit deal that placed trading borders between the United Kingdom and the province was a disgrace, although it in no way justifies the violence which has taken place. But Boris fixed the deal by leaving matters to the last possible minute and gave us only ‘no deal’ alternative which would have been even a bigger disaster.

The EU and Irish government are also to be blamed for our current Northern Ireland trading barriers. At the moment in Northern Ireland a majority wish to remain as part of our political and trading system, even if it would eventually be appropriate for them to opt in a referendum for a united Ireland. There needs to be direct trade between Ireland and the province, as under the Good Friday Agreement.