Labour’s poor performance in recent local elections show how it’s still failing to learn lessons that have been decades in the making. WILL BROWN sifts through the all-too-familiar responses and seeks a route to recovery that embraces all parts of the fractured party.

Labour today is the living embodiment of the old cliché that those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. For the sixth time in just over a decade, the party is responding to the gut-punch of defeat with a factional blame game and bewildered search for routes out of the abyss.

Left and right, in a disfigured mirror image of each other, reach for singular explanations of defeat that further their own sectarian purposes, be it Jeremy Corbyn or Brexit, Keir Starmer or the unions, moderation or radicalism. Others reach for the comfort-blanket of the usual responses – the need to reconnect, review policy, campaign more, modernise, listen rather than lecture, look outwards not inwards.

Left and right, in a disfigured mirror image of each other, reach for singular explanations of defeat that further their own sectarian purposes, be it Jeremy Corbyn or Brexit, Keir Starmer or the unions, moderation or radicalism. Others reach for the comfort-blanket of the usual responses – the need to reconnect, review policy, campaign more, modernise, listen rather than lecture, look outwards not inwards.

Little progress will be made unless the opposing wings of the party can engage in a sensible dialogue, one that doesn’t presume they possess all virtue and the other all fault; one that recognises that the causes of the party’s problems run deeper than betrayal by venal right wingers or deluded lefties.

Yet, while Labour’s electoral challenges are large scale, dynamic and increasingly difficult, the internal battle continues along tired old lines.

Merely comparing the two most recent periods – the slow-motion car crash of Corbyn’s last two years and Starmer’s inglorious first 12 months – familiar mistakes are clear to see: failure to define a clear message that connects with enough voters; a leader’s office increasingly isolating itself from MPs and the wider party; indecision over the party’s position on vital national challenges; confusion and factionalism in party HQ, leading to confused and misdirected campaigning; an inability to adapt to a shape-shifting and electorally adroit Tory party.

It’s not as if we don’t know about these failings. In their respective books on the Corbyn years, Owen Jones (author of This Land) and Gabriel Pogrund and Patrick Maguire (authors of Left Out), show us in exhaustive detail the hopeless response of the party leadership to the electoral conundrums it faced between 2017 and 2019.

The books tell remarkably similar stories, drawing on many of the same sources, although they come at the subject from very different standpoints. They tell how Corbyn shied away from confrontations and responded to difficult decisions by disappearing.

Facing opposition from outside the party and from its own MPs, the leaders’ office retreated into its inner sanctum, which itself eventually dissolved into ever smaller factions. Short-term accommodations replaced clear strategic thinking, messaging was confused, critics were demonised, allies were lost and new alliances were never built. As for Corbyn, so too Starmer?

Long-standing dilemmas

For more than a decade, Labour has struggled to find a clear message that unites its fractured support base on the pre-eminent political challenges facing the country, whether they be austerity, Brexit, national security or the pandemic.

Unlike his predecessor, Corbyn (left) seemed to resolve one of these dilemmas, only to be impaled on others. He made a decisive shift in opposing austerity, and the 2017 election appeared to show the widespread popular appeal of more radical economic policies as he achieved that rare feat of moving the Tories leftwards. Yet, not only did his leadership fail to understand the limits of this achievement – Labour continued to lack voters’ trust on economic matters – it then became paralysed in the face of Brexit and tone deaf on security threats, such as that from Russia.

Unlike his predecessor, Corbyn (left) seemed to resolve one of these dilemmas, only to be impaled on others. He made a decisive shift in opposing austerity, and the 2017 election appeared to show the widespread popular appeal of more radical economic policies as he achieved that rare feat of moving the Tories leftwards. Yet, not only did his leadership fail to understand the limits of this achievement – Labour continued to lack voters’ trust on economic matters – it then became paralysed in the face of Brexit and tone deaf on security threats, such as that from Russia.

Underlying his problem – as well as Ed Miliband’s before him and Starmer’s afterwards – is a historic electoral challenge that has been decades in the making. A number of studies attempted to identify the factors behind this, and started to chart a way out, but themselves fell foul of factional distortion or were sidelined amid the fray.

The Fabians’ For the Many?, for instance, published after the 2017 election, pointed out that the party continued to lose votes in heartland constituencies and that many long-standing Labour seats were retained by thin margins. Most tellingly, it warned that a ‘one more heave’ approach would not be enough to get Labour into power.

The Corbyn leadership and the left had no time for such sober analysis. Cock-a-hoop that they’d done better than expected, they shunned the idea of a serious review and rejected naysayers as outriders for the party’s right wing. Andrew Fisher, Labour’s executive director of policy from 2015 to ’19, rather belatedly acknowledged this mistake when he was quoted in Labour Together’s Election Review 2019 :

“I think that probably when most of the mistakes were made, looking back, is actually in the aftermath of 2017… At that point we probably should have sat down very soberly and gone ‘Okay, how do we now win, because we’ve done the easy stuff, we’ve won the low hanging fruit?’… Somebody should have just gone ‘Woah, we haven’t actually won anything yet.’ … Looking back we should have been a lot more strategic after 2017 than we were.”

That report laid bare, in even more impressive detail, the long-term trends that no leader – neither Gordon Brown, nor Miliband, nor Corbyn – had managed to reverse. It showed how, over four decades, Labour faced a decline in voters’ party loyalties, a shift in Labour’s class base away from the ‘traditional’ working class, a rise in Conservative support across England (London excepted), and an increasingly sharp generational divide as older voters moved rightwards.

Academic studies, such as Maria Sobolewska and Robert Ford’s Brexitand, have reinforced the point. Dr Paula Surridge of the University of Bristol, deputy director of UK in a Changing Europe, emphasises Labour’s difficulty in uniting disparate support bases.

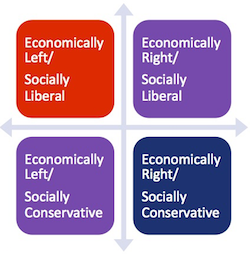

Its dilemma is summarised in the diagram left: while Labour and Conservative core votes are in the top left and bottom right, competition focuses on the purple squares. Unfortunately for Labour, those in the bottom left outnumber those in the top left by 2:1. In ‘The fragmentation of the electoral left since 2010’, in Renewal, Surridge wrote:

Its dilemma is summarised in the diagram left: while Labour and Conservative core votes are in the top left and bottom right, competition focuses on the purple squares. Unfortunately for Labour, those in the bottom left outnumber those in the top left by 2:1. In ‘The fragmentation of the electoral left since 2010’, in Renewal, Surridge wrote:

“Since 2010 [before the rise of UKIP] … those on the left economically who are not also ‘liberal’ in their social values have become less likely to vote Labour, whilst the ‘liberal’ left have become more likely to do so (reflecting the collapse of the Liberal Democratic vote). But the economic ‘left’ are not predominantly ‘liberal’; its ‘not liberal’ constituency outnumber the ‘liberals’ by around 2 to 1.”

Post-poll panic

In this context, it’s a sign of Labour’s lack of confidence that its response to the recent 2021 elections was initially one of panic. While catastrophising the results serves a purpose for some – the left to undermine Starmer’s leadership, the right to push for faster, greater change – it’s unclear why the leadership should have reacted this way, other than from a loss of nerve. Granted, after all of Boris Johnson’s failures and government corruption, being seven points behind in the popular vote and losing historic strongholds such as Hartlepool isn’t good in anyone’s book.

The results were uneven, however. The collapse of UKIP, Brexit and Reform UK didn’t lead to commensurate rises in Conservative votes. In Wales, in particular, Labour seemed able to recoup some lost leave voters and reinforce the party’s dominance. Scotland saw some modest recovery for Labour, and mayoral elections brought some significant Labour wins. While Labour lost overall control of high-profile councils, in some places this was despite a rise in its vote share (in Sheffield, for example, where eight seats were lost despite a 5 per cent rise in Labour’s vote across the city). The Tories also lost control of some councils in the south.

The results were uneven, however. The collapse of UKIP, Brexit and Reform UK didn’t lead to commensurate rises in Conservative votes. In Wales, in particular, Labour seemed able to recoup some lost leave voters and reinforce the party’s dominance. Scotland saw some modest recovery for Labour, and mayoral elections brought some significant Labour wins. While Labour lost overall control of high-profile councils, in some places this was despite a rise in its vote share (in Sheffield, for example, where eight seats were lost despite a 5 per cent rise in Labour’s vote across the city). The Tories also lost control of some councils in the south.

Seemingly unaware of the negative impact their interventions have on of their own side, Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson could not help but weigh in. Mandelson called rather nebulously for party reform, change and policy review, while Blair more hyperbolically demanded “total deconstruction and reconstruction” of the party.

Remaining hard-core Corbyn supporters have been just as quick to try and make short-term capital out of Starmer’s troubles, Owen Jones gleefully pointing out the weaknesses of this supposedly ‘more electable’ leader.

Yet while Jones is correct to point to the political bankruptcy of the right – at no point since Corbyn’s election in 2015 have they offered anything resembling a coherent political programme or strategy – neither has the left acknowledged its own political failings with the electorate, nor the decades-long task of challenging entrenched social conservatism.

Routes to recovery

Echoing previous ILP calls for alliance, co-existence and dialogue between left and right in the party, James McAsh made a convincing case on Labour List for the kind of broad church left the ILP has long argued for. He notes that the only centre left parties in Europe to have shown even small electoral recoveries recently – the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) and the Portuguese Socialist Party (PS) – have done so in alliance with more radical left-wing support.

Biden’s Democrats have also embraced, at least to some extent, the party’s left wing, not only to defeat Trump’s populism but to embark on a far more radical programme of change than many expected.

These lessons from America have been echoed by others calling for a Biden-like, radical work and jobs-focussed agenda at the centre of the Labour Party’s pitch. Jon Cruddas’ The Dignity of Labour is perhaps the most recent UK-focussed attempt to do this. Whether such an agenda can appeal to enough of the party’s warring factions, never mind be heard more widely through all the ‘culture war’ noise, is a moot point.

Others focus closer to home, stressing the gains made in areas where Labour pursued a radical local and regional agenda. In this view, Labour should take the opportunities that exist to explore local innovation and radicalism, as in Preston and a handful of other areas in the north west and south west of England.

Elsewhere, people argue for a radical change in the party’s day-to-day engagement with local communities. It’s a view we’ve heard before – reflected in Miliband’s Refounding Labour initiative, his call for activist, engaged and campaigning CLPs, as well as in numerous Labour leadership pleas to ‘do politics differently’, and Momentum’s ongoing efforts to revitalise and reconnect local parties to political struggles.

Paul Mason, writing in the New Statesman, maintains that Labour still has a role to play in effecting wider, necessary social change: “Labour needs to become a party in which all sections of the working class, with all their competing values and identities, can find a voice and a place. It cannot tolerate racism, sexism or homophobia, just as it can’t tolerate anti-Semitism. But it can offer a route away from prejudice for working people in thrall to the right-wing ideologies of the tabloids and phone-in shows.”

Making any of this happen, or even having a constructive dialogue about these strategies, remains a difficult task as time and again local party business is dominated by inward-looking factional point-scoring and immediate electoral campaigning priorities.

Meanwhile, the fractures between left and right continue – the left shunning the potential of engaging constructively with the Starmer leadership, and Starmer himself seeming intent on actively sidelining the left.

As McAsh concludes: “Neither [centre nor radical left] is big enough alone to appeal to the broad spectrum of voters we need, but together we might have a chance. Making this coalition work may not be easy but it’s the only choice we have.”

—-

See also: ‘Fade to Mauve: Starmer’s Leadership One Year On’, by David Connolly.

26 August 2021

Thanks for your comment, Ian. You might be interested in David Connolly’s latest piece here.

6 August 2021

What Starmer is doing is far, far more than a ‘lurch to the right’. It’s no less than the destruction of the Labour party as it has existed since its inception. When Starmer has finished, all the power will lie at the top and there will be a greatly diminished and reduced membership, probably with an advisory only function. It really will be Labour in name only. This isn’t a battle for the Labour left or for the soul of the party – it’s a battle for Labour’s very existence as any kind of democratic, socialist party.

30 May 2021

While there’s a lot in Will Brown’s evaluation of Labour’s electoral failures and it’s true, a house divided (his fractured party) cannot stand. As such, Labour is unlikely to win over the British electorate anytime soon. But his route to recovery is thin gruel and less than persuasive. Of course, Will is right to say Labour’s demise has been a long time in the making, with the fracture of working-class support predating Brexit, Corbyn, Miliband, Brown, Blair and Kinnock.

But that’s the point – Labour has been in and out of power nationally and locally for decades, despite doing some good and some not-so-good things. But over these years, we have seen the rise of neoliberalism; the embrace of outsourcing; the demise of heavy industry and the manufacturing base; the emergence of deprived communities with the life sucked out of them, neighbourhoods largely left to rot, infested by drugs, anti-social behaviour and criminal gangs … and Labour has done next to nothing.

The things that really matter to families, especially those at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder – a secure job, a living wage, a decent home, safety and security, and a sense of wellbeing and hope – have been turned upside down. In large measure, Labour governments locally and nationally have proved powerless to help and are often part of the problem, rarely the solution.

Take the Scottish town of Kirkcaldy. The constituency of Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath had been a safe Labour seat throughout its existence, but was won by the Scottish National Party in 2015. When my son was living in Fife, I was a regular visitor to the colloquially known Lang Toun. That was in 2006/10 when Gordon Brown (a good man) was MP and prime minister, and I was struck by its general decline, levels of unemployment and extremes of poverty. Even the charity shops were closing down.

One of the common complaints among my extended family and friends was the shortage of affordable and social housing. Many complained about porous borders, claiming their government was allowing millions into the country at the expense of jobs and homes for their sons and daughters. They told of routinely being bumped off council and social housing waiting lists.

Net immigration was 300,000 or more yearly – equivalent to a city the size of Newcastle, or six Kirkcaldys every year. It was and is unsustainable. They complained, not because they were racist or hated immigrants, but because it was true.

My stock answer was to tell my family and friends to raise concerns with their local Labour councillors and MP, their community champions. But the few who did got short-shift. I don’t know if anyone raised their concerns with Gordon Brown, but one or two did contact local councillors and Labour members, and (in a nutshell) were told their moans about immigration were the stuff of racism, a selfish disregard for the plight of asylum seekers much worse off than themselves. That type of response went down like a ton of bricks.

It is for these reasons many working-class people turned their backs on Labour and voted for the SNP, for Brexit and latterly for the Conservatives. While Labour MPs and members like to talk diversity, it no longer looks like a party of labour, in all its disparate forms.

I myself voted for Brexit (not an easy decision) and have been dismayed how condescending, nasty and malicious Labour people have been in labelling Brexiteers thick-as-mince and racist little Englanders who are harking back to the days of empire and a long-lost past.

While some might fit the racist description, they are few and far between and most working-class Brexiteers and working-class conservatives I know are decent, hardworking, law-abiding and lovely people who just happen to think differently to the Labour tribe.

On the issue of broad church politics, demographics and political identities, anyone serious about change should look at our outdated voting system, support proportional representation and engage in electoral packs with the Greens, Liberals and the Yorkshire Party. It would go against Labour’s policy of standing candidates in every constituency but would mean working together for a common cause without compromising core values. Thinking on that scale is anathema to the Labour Party and it’s an issue the ILP never mentions or considers.

Despite changing demographics, polls show that there is a progressive majority in Britain, and that a PR electoral system would make a Tory majority government impossible. Now that might be a route to recovery.