How can progressives describe the society they wish to build if they cannot first imagine it? CHRISTOPHER OLEWICZ recalls Fenner Brockway’s forgotten novel and laments the lack of utopian fiction for a post-Covid world.

With vaccine rollouts allowing us to dream once again of a return to ‘normality’, our thoughts drift towards the question of what normality will mean. Will we be placed back in December 2019 as if nothing happened? Or have our lives been sent down a path of irreversible change?

In the early months of the lockdown, commentators were quick to list the ways in which our lives would be improved by the pandemic, from the extinction of the daily commute to transforming our relationship with food. Yet much of that hope has now vanished. Mutual aid groups have faded into memory and the heralded return of ‘community’ seems to have been a temporary phenomenon as those requiring support are once again marginalised and brandished with that most derogatory social label, ‘dependents’.

In the early months of the lockdown, commentators were quick to list the ways in which our lives would be improved by the pandemic, from the extinction of the daily commute to transforming our relationship with food. Yet much of that hope has now vanished. Mutual aid groups have faded into memory and the heralded return of ‘community’ seems to have been a temporary phenomenon as those requiring support are once again marginalised and brandished with that most derogatory social label, ‘dependents’.

None of us can predict what may happen, of course, but one of the ways successive generations have tried to visualise the future is through utopian literature. In the 19th century it was popular and commonplace, despite narratives that often acted as nothing more than loose framing devices for the future world envisaged by the author.

Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) and William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890) are two famous examples. In the United States Looking Backwards became the biggest selling book after the bible in the decade following its publication. More than 150 Bellamyite ‘nationalist clubs’ were formed to disseminate his arguments and bring about its vision via the Populist Party.

The ‘Great War’ changed everything. Since then, fiction has become almost exclusively pre-occupied with the idea of dystopia. Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1921), Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1931) and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1948) all imagined totalitarian societies in which privacy, free-thought and intimate relationships are non-existent and social inequality is entrenched.

Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) described an alternative dystopia in which a wealthy elite subdues the population and dehumanises women, while Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), now a successful TV drama series, portrayed a hyper-religious society that has robbed women of their sexual freedom.

Meanwhile, the aesthetic of Blade Runner, the 1982 film adaptation of Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep, with its man-made environmental catastrophes, has become de rigueur in conceptions of the coming world.

The proliferation of internet conspiracy theories is related to these grim descriptions. Independently published works such as The COVID-19 Illusion: A Cacophony of Lies; COVID-19: The Great Reset; and The Truth about Covid-19: Exposing the Great Reset, Lockdowns, Vaccine Passports and the New Normal present a dystopian account of mass-unemployment and mass-surveillance under a self-serving and cruel government.

A few utopian novels and essays have appeared sporadically, but none have attained significant public prestige. Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge (1990) describes an ecologically motivated utopia in 2060s California, while Ralph Nader’s Only the Super Rich Can Save Us (2009) describes a world in which several billionaires come together to save American capitalism from itself.

Even young people, it seems, are more likely to imagine The Hunger Games than News from Nowhere. Last year, King’s College London organised a Utopia Now project for which young people from south London wrote 1,000-word stories about the future, with five selected for a flash fiction anthology, One Day in 2070.

In one, Drip, Drip, Drip, 2070 is described as: “a year of death, despair, destruction and doubt… Every man, woman, and everything in between for themselves. A man’s opinion still overpowers any women. Homeless people are still homeless, poor people are getting poorer and the rich are still getting richer. The government only care about their power and money and not the people being affected by their cruel laws.”

Inside the Future, meanwhile, portrays a world where robots and drones are used to create an apparent paradise, but people are addicted to technology and socialising has disappeared. In What a Wonderous World career chips are installed into citizens and pregnancy is outsourced to laboratories where babies are grown in incubators.

Utopia & politics

Who then will write the utopian novel for the post-Covid world? Have we become so fearful of the future that we cannot imagine such a world?

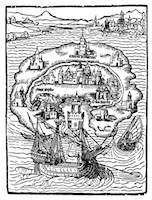

In 2018, Ruth Potts spoke of the importance of utopian thinking in contemporary politics as she reflected on the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia. Utopia, she suggested, had been misunderstood, dismissed on ideological or feasibility grounds. It is not simply a destination, she said, but the process of imagining a future and taking steps to achieve it. In times of profound change – the French revolution or the industrial revolution, for example – people “reach for forms that help us reimagine and recreate the world around us”.

In 2018, Ruth Potts spoke of the importance of utopian thinking in contemporary politics as she reflected on the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia. Utopia, she suggested, had been misunderstood, dismissed on ideological or feasibility grounds. It is not simply a destination, she said, but the process of imagining a future and taking steps to achieve it. In times of profound change – the French revolution or the industrial revolution, for example – people “reach for forms that help us reimagine and recreate the world around us”.

“We can look back historically, and draw inspiration from the co-operative movement, the myriad of working-class movements around the world who have organised around cultures of self-help and mutual aid – and continue to do so today.” The dismissal of utopia is a form of social control, a means of emphasising that the current way of doing things is optimal and should be accepted.

In his recent book The Dignity of Labour, Jon Cruddas argues that the political left has “lost its language” in relation to the traditions and value of work, and has lost itself in “a strange new utopia … [which] will provide liberty through abundance and a workless future powered by automation, machine learning and artificial intelligence”. Until recently, Cruddas notes, a “capitalist realism” and a “neo-liberal dystopia” held sway within left opinion, but now “a brave new world of post-capitalism, even ‘fully automated luxury communism’ is expected.”

Such utopian thinking, Cruddas suggests, would be “unrecognisable to my east London constituents” and people living in other communities “beyond the reach of a remote liberal cosmopolitanism”. To reconnect with voters, Labour should propose a Good Work Covenant to once again establish itself as the party of the working-class. A commitment to Universal Basic Income and “automated luxury communism” – a decoupling of reward from work – would be a step in the wrong direction, he states, and would not win an election for Labour.

The Dignity of Labour takes a hard look at the political reality facing a Labour Party torn between appealing to both middle-class liberals who have been able to work from home, and working-class unskilled and semi-skilled workers who have lost their livelihoods. Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto is a utopian description of a possible future in which we “feed a world of nine billion, overcome work, transcend the limits of biology, and establish meaningful freedom for everyone”. In this, it shares much with News from Nowhere and Looking Backwards, but it is not a political prescription for the here and now.

Brockway on board

So, what does this have to do with Fenner Brockway and the ILP? Brockway was famed as a prominent politician of the left, a newspaper editor and author, but less well known is his brief foray into fiction and his one utopian novel, Purple Plague. Published in 1935, it is an account of an ocean liner cut off from society by an outbreak of a plague that gestates for 10 years before killing the patient.

The idea came to Brockway during a 1933 trip to the United States, his third visit in four years. On his first in 1929 he enjoyed the opulence of first-class life as a guest of Alastair MacDonald, the architect son of Ramsay, who was travelling to New York to study skyscrapers. He visited again in 1931 after losing his seat in that year’s disastrous election, and encountered a country in the depths of the great depression.

Two years later, following the ILP’s disaffiliation from the Labour Party, he visited a third time, and witnessed the optimism of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which was committed to public spending on a scale unthinkable in Britain. He met former Communist leader Jay Lovestone, Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas, and the secretariat of the League for Industrial Democracy.

On his return, Brockway enjoyed the presence of a troupe of Paramount dancing girls, who were travelling across the Atlantic to perform on a European Tour. Writing in his memoir, Inside the Left, Brockway recounts:

“Among them I was surprised to find university students whose careers at college had been interrupted by the depression; two of the girls, as I learned subsequently when I met them in Paris, actually took courses at the Sorbonne by day whilst they danced at night… The girls were asked to stage a show in the first class: tourist and third passengers were invited on the condition that they wore evening dress. At the suggestion of a few of us who wanted to see the show, the girls told the captain that they would not dance if the dress qualifications were maintained. The captain gave way, and that night the tourist and third class invaded the first-class quarters en masse.”

Life on board mirrored class divisions “exactly”, he reflected. The tourist class, Brockway says, was the “great human mixer”, containing “professional men and women, vaudevillians, businessmen, working-class families above the poverty line, students comfortably off [and] people bored by the listlessness of first-class company”.

“There are two nations within each nation… [and] there are certainly two ships within each ship. The passengers see the crew going about their work, but they never see the underworld of the ship where the crew live. It is a world of sharp contrast. In the first class – spacious saloons and lounges; broad promenades; roomy cabins with sitting rooms and bathrooms attached. In the crew’s quarters – hot and crowded kitchens; noisy, pulsating engines; smelly and dark passages; mess rooms with wooden forms and oil-cloth tables; and sleeping accommodation with bunks so close that it is difficult to turn between them.”

It was this first-hand experience of the intolerable conditions sailors and stewards suffered that shaped the outline of his novel. What if a social revolution were to occur on board? he thought. Under what circumstances would it be allowed to flourish?

Plague & revolution

The novel he eventually wrote, Purple Plague, opens as Dr Robert Haden reaches port just in time to board a ship to England. He has been tasked with producing a cure for the titular plague, and refuses the first-class suite offered to him. We are introduced to Connie, Hilda and Vera, members of a troupe of dancers. Hilda is an intellectual with a library of books by Aldous Huxley, Bertrand Russell, Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lews, Bernard Shaw and Edward Carpenter – no doubt favourites of Brockway.

At first, all goes smoothly. Life on board settles into the pattern Brockway encountered during his voyages. A good time is had. There are flirtations between dancers and male passengers, notably with MacMillan, a lecturer in politics and economics at Columbia University, who is travelling to “sit at the feet of Harold Laski for six months”. At dinner, he meets Schwartz, a retired businessman who is taking his first vacation after 50 years selling clothing in Cleveland, Ohio.

At first, all goes smoothly. Life on board settles into the pattern Brockway encountered during his voyages. A good time is had. There are flirtations between dancers and male passengers, notably with MacMillan, a lecturer in politics and economics at Columbia University, who is travelling to “sit at the feet of Harold Laski for six months”. At dinner, he meets Schwartz, a retired businessman who is taking his first vacation after 50 years selling clothing in Cleveland, Ohio.

Below decks is a different story. The centre of social activity among the crew is Pantry Square – “the recess where from pigeon-holes they dished out soup and salmon and veal and pheasant and asparagus and sweets for the passengers; the same recess where, when the passengers were through their seven courses” the stewards “grabbed up the leavings or ate their regulation ration … pickled pork”.

It is here that William Wells, first-class steward-waiter and Communist, and Franklin, his trade unionist friend, dream about organising the crew to stand up to the shipping company and their moderate union.

A while later, Wells meets Joe Nathan, a trade union official who has received a Labour Foundation fellowship to study working class organisation in Europe. Together they dream of a revolution on board that will emancipate the third class passengers and crew from their lives of relative discomfort. “We’re slaves of the bosses and slaves of the union,” Wells says. “There’s only one thing that will change our conditions. A revolution!”

When one of the passengers contracts the purple plague, the American and British governments announce that the ship will not be allowed to dock at their ports, nor the passengers allowed to leave. They and the crew face being confined to the ship for 10 years, condemned to sail the seas in fear of eventual death.

Wells and Nathan formulate a plan to take control. “Do you think the enginemen, sailors and stewards are going to stick to their conditions for 10 years, working for those bloody idlers in the first class?” Wells asks. “Are you boys in the steerage going to put up with this? Course, I’m right. What did Lenin say? He said a revolution requires three conditions – a crisis, discontent among the workers and disunity among the rulers… You should hear them in first class. They grumble at the captain all through the meal. Some of them even say he’s not half the man you are.”

Together with Franklin and others, Wells and Nathan successfully take control of the ship and form a council elected by the crew and third-class passengers. Class distinctions are abolished and everyone is required to do part of the ship’s work in return for an equal share its comforts. MacMillan is appointed commissar for foreign affairs under Nathan, and Hilda becomes secretary.

She spurs on the development of a university, a newspaper, a theatre, organised sports and art and crafts, all things vital to support cultural life. Accommodation is redistributed, with first-class cabins available to families. A famous novelist, Sinclair Lewis, writes the story of the revolution, ‘The Ten Days that Shook the Atlantic’, while Professor Sefton, a banker travelling under a pseudonym, helps to establish a currency.

The rest of the novel charts the success of this egalitarian society and Dr Haden’s quest to isolate the germ and create an antidote. It ends with a plea for the “example of the ship” to be taken “to the world”.

Brockway himself was disatisfied with the novel and was first to admit it was not a great work. During the Second World War, on nights spent in the bomb shelters, Brockway revised the novel, turning it into a radio script called Red Liner, with much of the dialogue from the original remaining intact. It was eventually published in the mid-1960s. It does not appear to have ever been performed.

Yet, like so many utopian novels, the ideas presented in Purple Plague and the message it conveys are ultimately more important than the narrative. It portrays a positive revolution in which high-minded ideals are placed front and centre as the crew and passengers fight to make the best of their situation.

Novels of this kind are desperately needed now, for how can progressives describe the society they wish to build if they cannot first imagine it?

—-

Christopher Olewicz is a historian and director of Principle 5: Yorkshire Co-operative Resource Centre based in Sheffield.