GRAHAM TAYLOR recounts the tale of a long-forgotten Bermondsey ILPer who once scored a crucial goal for England before joining the church in south east London where he was a keen supporter of Ada and Alfred Salter.

In 1886 the England football team played against Wales in Wrexham. Wales were ahead at half-time but in the 75th minute England won a free kick. A young centre half took the kick and scored the equaliser, after which England went on to win.

The centre half was called Andrew Amos (left) and he hailed from a distinguished middle class family of eminent lawyers, Anglican clergymen and political radicals. Given this background, it is perhaps not surprising that Amos soon turned from football to religion, becoming the rector of St Mary Rotherhithe in south east London, and then to politics, becoming a supporter of Ada and Alfred Salter in the ILP stronghold of Bermondsey.

The centre half was called Andrew Amos (left) and he hailed from a distinguished middle class family of eminent lawyers, Anglican clergymen and political radicals. Given this background, it is perhaps not surprising that Amos soon turned from football to religion, becoming the rector of St Mary Rotherhithe in south east London, and then to politics, becoming a supporter of Ada and Alfred Salter in the ILP stronghold of Bermondsey.

The Amos family, although Scottish by origin, had risen to prominence in India where Andrew’s grandfather, also called Andrew, was born. Back in England he became a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and first professor of English Law at University College London. His wife, Margaret Lax, from the village of St Ippolyts in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, had a similar background. Her father, Reverend William Lax, was professor of astronomy at Cambridge.

By 1837 grandfather Amos was a member of the Governor General’s Council in India, taking the place of Lord Macaulay, but he was not some stooge of the establishment. Amos had been educated at Eton with Shelley and, like the great poet, had radical ideas.

Margaret Amos gave birth to a son, James Amos, in St Ippolyts in 1829. He chose a career in the church and became vicar of St Stephen in Southwark. In 1861 James married Frances Karr Snape and the footballer, Andrew Amos, was born to them on 20 September 1863. Andrew was baptised on 20 October by his own father at St Stephen’s and the census of 1871 shows James and Frances with six children and five servants (cook, housemaid, nurse, assistant nurse, monthly nurse).

By 1875 James had married again following the death of Frances, and his new wife, Anne Pike, a widow, swelled the household with another five step-children and a governess. Andrew left this over-populated dwelling for boarding school – Charterhouse, in leafy Godalming, Surrey.

In the 1870s the main sport at Charterhouse School was football and Amos played for the school team, the Carthusians. When he went to Clare College, Cambridge, in 1882 he played for the university and team formed two years earlier that strongly upheld values of amateurism, not only rejecting any form of payment as ‘ungentlemanly’ but even scorning competitions played for cups.

Amos played for Corinthian until 1889, and made 47 appearances altogether. In 1884 Corinthian FC toured the north of England playing against the rising working class clubs that were edging towards what the elites regarded with disdain as sordid professionalism. In their first match against Blackburn Rovers (the FA Cup winners, and regarded as champions of England), Corinthian crushed working-class Blackburn in their own stadium 8-1. Amos played at centre half in this famous match.

Football’s class roots

The future of football lay, of course, with these ‘sordid’ professional clubs and their working-class followers. But the initial superiority demonstrated against Blackburn shows that public schools were early hot-beds of the modern game. Some public schools had started developing forms of organised football in the 1820s (Amos’s Charterhouse was a leading force) and players from public schools became founders of the sport’s formal bodies, such as the Football Association, as well as pioneering the game around the world.

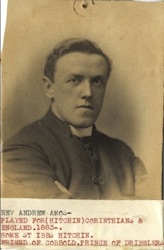

Some of the early great players were at school with Amos. Nevill ‘Nuts’ Cobbold (1862-1922), for example, the so-called ‘Prince of Dribblers’ (left), said to be the finest dribbler ever seen, and one of the most famous footballers of the time.

Some of the early great players were at school with Amos. Nevill ‘Nuts’ Cobbold (1862-1922), for example, the so-called ‘Prince of Dribblers’ (left), said to be the finest dribbler ever seen, and one of the most famous footballers of the time.

He won four blues at Cambridge between 1883 and 1886, and played nine times for England, scoring seven goals, a strike rate equalled by only a handful of players since. His legs swathed in rubber bandages and ankle-guards, he had a most peculiar shuffling run from which he unleashed powerful shots at goal.

Cobbold came from a family of Conservative politicians and his views on football were conservative too. Not only was he a proud amateur but he regarded the novel tactics of heading and passing the ball as distasteful, almost cheating. As a gentleman, Cobbold never headed on principle. Amos, on the other hand, was a liberal. He was renowned for his heading ability, still rare in the 1880s, and for his accurate forward passes, feeding the attack.

Also contemporary with Amos at Charterhouse were the Walters brothers, Arthur Melmoth Walters and Percy Melmoth Walters – often referred to as ‘morning’ and ‘afternoon’ in allusion to their initials.

Percy (1863-1936) was one of the all-time greats. He was a defender and made 13 appearances for England at full-back, five as captain. On football philosophy, the Walters brothers also differed from Cobbold. They favoured the ‘combination game’ of passing and teamwork as developed by the Royal Engineers.

Amos also played alongside notable players who weren’t from Charterhouse. Tinsley Lindley (1865-1940) was a great forward for Nottingham Forest, scoring 14 goals for England in 13 internationals. The great goal-scorer, Charlie Bambridge (1858-1935), was slightly older than Amos. He made 18 appearances for England and was England captain twice, while his father was William Bambridge, a schoolmaster at Eton, missionary to New Zealand and Royal Photographer to Queen Victoria.

Bambridge (‘Bam’) was also the subject of a legendary football story. He broke his leg and was not expected to play in a local cup final, yet he arrived wearing a large shin-guard outside his stocking and scored the winning goal. When asked how his broken leg had stood up, he replied: “Very well”, adding, “I wore the shin guard on the sound one.” This anecdote does have the hallmarks of a football yarn, but the tale comes from the time and fits with Bam’s known character.

Amos reached his football peak in 1885/86 when he received his two England call-ups. In the first against Scotland at the Oval, Kennington, on 21 March 1885, Amos played left-half, while up front were Bambridge and Cobbold, and behind him were the Walters brothers. Scotland were also strong and the match was drawn 1-1. In 1886 Amos was selected again to play against Wales when he scored that crucial goal from a free-kick to level the score.

It is very likely Amos would have played for England again but instead he turned suddenly to religion. In 1887 he became a curate in Durham and in 1888 was ordained an Anglican priest.

The following year he became priest-in-charge of the Clare College Mission in Rotherhithe, based at Abbeyfield Road on the edge of Southwark Park. He worked there until 1898 and while there married (in 1895) an Irish woman, Susan Connolly, at St Michael’s Church in Limerick. Susan was the daughter of Reverend Robert Connolly, rector of the protestant Longhill Church at Shanagolden.

Religious calling

Why did Amos take up religion so suddenly? It was surely connected with the moral panic of the mid-1880s after the revelations about the London slums exposed by Andrew Mearns in Bitter Cry of Outcast London (1883) and the subsequent establishment of Toynbee Hall.

Clare College decided its contribution would be the “Christianising of some spiritually destitute district” and this made them think of Rotherhithe. They already owned property there and opened the church in Abbeyfield Road in 1886. Andrew Amos, born and bred in nearby Southwark, must have seemed a God-send. Who could be a better attraction to their boys’ clubs than a local England football star of Christian convictions?

Clare College decided its contribution would be the “Christianising of some spiritually destitute district” and this made them think of Rotherhithe. They already owned property there and opened the church in Abbeyfield Road in 1886. Andrew Amos, born and bred in nearby Southwark, must have seemed a God-send. Who could be a better attraction to their boys’ clubs than a local England football star of Christian convictions?

Just as suddenly as he left football, Amos left London in 1898 to become rector at Datchworth in Hertfordshire. In his rural retreat he co-authored a book with William Woodcock Hough called The Cambridge Mission to South London, published in 1904. Hough, later Bishop of Woolwich, ran the Cambridge Corpus Christi Mission near the Old Kent Road, not far from Amos in Abbeyfield Road.

Amos’ book offers some clues as to why he may have turned to socialism and the ILP. He says the mission district contained 4,000 to 5,000 people housed in two-storey buildings, each containing from four to eight rooms occupied by two, three or more families.

“As a whole the population is not poverty-stricken, though it lies on the verge of being so, as a few weeks’ illness of the breadwinners reduces the family to sore straits,” he writes.

The vicinity of Southwark Park kept the air sweet, but everything was deadly monotonous, like the rest of south London. As for religious work, “the chief obstacle is an absolute indifference”. Even “the specious promises of Social Democracy”, he adds, gain no adherents, since “existence is much too grim and much too monotonous in its actual reality for the toiling labourers to think much about anything”.

This remark, apparently damning socialism, may seem contradictory in a man soon to be joining the ILP, but the historical context must be understood. The term ‘Social Democracy’ refers to the hardline Social Democratic Federation (SDF) of Henry Hyndman not to the idealistic Independent Labour Party of Keir Hardie and the Salters.

Amos would certainly not damn all socialism since many of his family were Christian socialists. Sheldon Amos, his uncle, was a friend of FD Maurice, the Christian socialist leader, and his wife, Sarah, was superintendent of the Working Women’s College, a Christian socialist enterprise.

Municipal revolution

The couple deliberately chose to live in one of the poorest parts of Holborn where Sarah became friends with Katherine Price Hughes, in whose west London Mission Ada Salter enlisted as a ‘Sister of the People’. Their son, Maurice Amos, was a friend of Bertrand Russell at Cambridge, then a liberal adviser to the Egyptian government, and then, like the Salters, a Quaker.

In 1907 Amos returned to south London, apparently reinvigorated by his period of rural reflection. From 1907 to 1917 he was vicar of St Ann’s Lambeth, and from 1917 rector of St Paul’s Deptford, before becoming rector of St Mary Rotherhithe in 1922.

The poverty in these south London parishes indicates his new political orientation. He arrived in Rotherhithe just in time for a municipal revolution. That November Labour, faced by a divided Liberal Party, won both the council and parliamentary elections. Ada Salter became mayor and Alfred Salter was elected MP. Susan Amos became a Labour councillor, and Andrew soon became a Labour alderman. The deadly dull labourers he had despaired of in 1904, who did not “think much about anything”, had now awoken from their slumbers and voted in the ILP.

The poverty in these south London parishes indicates his new political orientation. He arrived in Rotherhithe just in time for a municipal revolution. That November Labour, faced by a divided Liberal Party, won both the council and parliamentary elections. Ada Salter became mayor and Alfred Salter was elected MP. Susan Amos became a Labour councillor, and Andrew soon became a Labour alderman. The deadly dull labourers he had despaired of in 1904, who did not “think much about anything”, had now awoken from their slumbers and voted in the ILP.

In the next few years Ada transformed the Bermondsey environment, planting 9,000 trees, covering the deadly dull borough with flowers and children’s playgrounds, and designing an estate of model council housing, Wilson Grove. Her husband, Alfred, as well as being the MP, transformed the health service with free medicine, clinics, innovative health propaganda films and a solarium, thus establishing in Bermondsey ‘an NHS before the NHS’.

Andrew died on 2 October 1931 and his funeral at St Mary Rotherhithe was attended by Alfred Monahan (his brother-in-law), an Anglo-Catholic who later became Bishop of Monmouth. Councillor Susan Amos, younger than Andrew, continued to campaign with the Salters despite the ILP’s disaffiliation from Labour in 1932. She was still on Ada’s Beautification Committee in 1935, along with George Balleine, the ‘red vicar’ of St James, and was on Alfred’s Public Health Committee when the ground-breaking Bermondsey Health Centre was opened in Grange Road in 1936.

There is little memory of Andrew Amos in Rotherhithe today. There is a housing estate in Rotherhithe Street named after him (pictured above), but that is all. Normally an England football international would be appreciated in some way, and even more so a dedicated social worker who had been based at the Clare College Mission and worked with the Salters for the welfare of the people.

Maybe football, politics and religion do not seem natural companions. One thing seems certain, however, Andrew Amos remains the only ILP member to have scored a goal for England.

—-

This article first appeared earlier this year in the Redriffe Chronicle, history journal of the Rotherhithe and Bermondsey Local History Society.

Graham Taylor is the author of Ada Salter: Pioneer of Ethical Socialism published by Lawrence & Wishart and available to buy here for £20.00.

Barry Winter’s review of the book is here.

Graham Taylor’s ILP pamphlet, Ada Salter and the Origins of Ethical Socialism, can be ordered now from our Publications page.

The 100th anniversary of Ada and Alfred Salter’s 1922 election successes will be celebrated next year with a series of events in Southwark organised by the Salter Centenary Project. More details to come.