With conflict brewing on the Russia-Ukraine border, and talk of an ‘unthinkable’ war in Europe, MARIA GOULDING turned to ‘one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time’, a book that speaks the unspeakable, and finds truth in the aftermath of horror.

On Friday 21 January presenter Mishal Husain mooted on Radio 4’s Today programme about the unthinkable possibility of a war in Europe. Footage on Channel 4 News the previous night showed Russian tanks massing on the border of Ukraine and heavily armed soldiers in driving winter snows.

Germany is cautious because of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline connecting it to Russia. But British and American voices seem more gung ho. Who knows what will have happened by the time you read this.

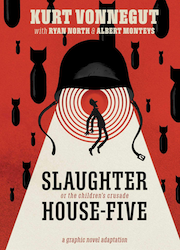

All this has coincided with my re-reading Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut’s novel of 1969 written at the height of the Vietnam War. Subtitled The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, it is a book about the writing of a book about the story of the firebombing of Dresden (see left), which Vonnegut had witnessed himself, but told obliquely through the time-travelling eyes of the hapless Billy Pilgrim.

All this has coincided with my re-reading Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut’s novel of 1969 written at the height of the Vietnam War. Subtitled The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, it is a book about the writing of a book about the story of the firebombing of Dresden (see left), which Vonnegut had witnessed himself, but told obliquely through the time-travelling eyes of the hapless Billy Pilgrim.

Billy’s experiences are framed by the narrator’s opening chapter explaining how he came to write the book after trying for 23 years. It is his war buddy’s wife, Mary, who gives him the key when she turns on him furiously and says: “You were babies in the war… But you’re not going to write it that way… You’ll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you’ll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne… And war will look just wonderful.”

Another character, a movie maker, turns to him incredulously and asks: “Is it an anti-war book? Why don’t you write an anti-glacier book instead?”

Billy is a gangling scarecrow of a young man, unarmed and ill-clad when he is taken prisoner behind enemy lines. He endures an agonising train journey to the prisoner of war camp where the English interns have created a cosy world for themselves, thanks to a clerical error early in the war that meant the Red Cross shipped 500 parcels to them instead of 50.

They greet their rag tag American guests with a banquet and gifts, although unknowingly, the candles and soap had been made from the rendered fat of victims of the extermination camps. Billy becomes hysterical during a performance of Cinderella, the evening’s entertainment, and is carried off to the hospital where he is sedated.

His recuperation does not last long. The Americans are taken to Dresden, incarcerated in an underground abattoir and work as contract labourers during the day. After the fire bombing, the city – which had looked like “a Sunday school picture of Heaven” when he arrived – now looks like the face of the moon. When he returns in 1967, the narrator says it looked like Dayton, Ohio, apart from the open spaces: “There must be tons of human bone meal in the ground,” he muses.

After the war, Billy has to find a way to somehow live with his experiences. This is surely the story of someone living his life with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before the term was commonplace. He becomes “unstuck in time” and the story is a set of intercut and random fragments with the thread of Billy’s war story running throughout.

So we jump randomly between the war, his later career as a successful optometrist, back to his childhood, then the plane crash that he alone survives, and back again to the early days of his marriage. “He is in a constant state of stage fright, he says, because he never knows which part of his life he is going to have to act in next.”

Heart-searching humour

So far so grim, but this is a darkly comic book with a searing ironic tone. The physical descriptions of Billy wrapped up in an azure curtain, with silver boots rescued from the stage set of Cinderella, portray him as a holy fool. Other characters – the bullying but pathetic Roland Weary, the vengeful Lazzaro, poor old Edgar Derby who is executed for taking a teapot after the Dresden raid – all have unforgettable lines.

We are constantly confronted with the absurdity of situations and the deadpan humour Vonnegut (left) employs to speak about the unspeakable. This is not glib, however, or written for amusement. In a 2019 Guardian review Christopher Wordsworth writes: “The oddest and most directly and obliquely heart-searching war book for years proves how art, in its own good time, can find a way.”

We are constantly confronted with the absurdity of situations and the deadpan humour Vonnegut (left) employs to speak about the unspeakable. This is not glib, however, or written for amusement. In a 2019 Guardian review Christopher Wordsworth writes: “The oddest and most directly and obliquely heart-searching war book for years proves how art, in its own good time, can find a way.”

The book speaks a truth, but it is anything but hopeful. As part of his strategy for survival, Billy becomes, not only a time traveller but also a space traveller. Inspired by the science fiction of Kilgore Trout, Billy is taken by little green men to the planet of Tralfamadore where they have a completely different concept of time from that on Earth.

There, time is not chronological. As a Tralfamadorian puts it: “I [see] all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanation. It simply is.”

When questioned about the Tralfamadorian belief in freewill, Billy is told: “I wouldn’t have any idea what was meant by ‘freewill’. I’ve visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe, and I have studied reports on one hundred more. Only on Earth is there any talk of freewill.”

Some readers may baulk at this science fiction element of the book, finding it absurd and fantastical, but the great strength of this strand is that it throws up taken for granted assumptions and forces us to consider completely different ways of thinking about questions like time, determinism and freewill.

As far as wars are concerned, the narrator (not necessarily Vonnegut) is saying that although war is terrible, we are trapped in a never-ending cycle and it will keep on happening. We are just “bugs in amber”. The Tralfamadorian idea that everything has been pre-determined and nothing can be done about it may give Billy some comfort. Indeed, it could be that the response to trauma is passivity.

Quietism, however, is a deeply pessimistic perspective. We may not agree with fatalism but we have to provide alternative arguments and evidence that war is not inevitable and that political solutions must be pursued at all costs. Opposition to violence is an ongoing struggle. However, we still have to confront the painful truth that everywhere in the world today wars are going on. Wikipedia has reported 40 ongoing conflicts in 2020 and 2021.

Confronting painful truths is not to everyone’s taste of course. Slaughterhouse-Five has been banned from school libraries many times in the United States. In 1972 a Michigan circuit judge described the book as “depraved, immoral, psychotic, vulgar and anti-Christian”, while in 2011 it was banned in Missouri after a university professor claimed that it “contains so much profane language, it would make a sailor blush with shame”. When it was burned by school officials in Drake, North Dakota, in 1973 Vonnegut himself responded in a letter to the school board:

“It is true that some of the characters speak coarsely. That is because people speak coarsely in real life. Especially soldiers and hardworking men speak coarsely, and even our most sheltered children know that. And we all know, too, that those words really don’t damage children much. They didn’t damage us when we were young. It was evil deeds and lying that hurt us.”

This reminds us of the powerful forces that are determined to shut down debate and to ban anyone writing something about which they disagree. Far from banning this book, I think it is a must read, or a re-read for those of us who can still remember the sixties.

—-

Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, by Kurt Vonnegut, was first published in 1969.