CHRISTOPHER OLEWICZ looks back 90 years at Fenner Brockway’s ground-breaking report on destitution in 1930s Britain. With the current cost of living crisis, he asks, is ‘literal starvation’ once again stalking the nation’s poorest communities?

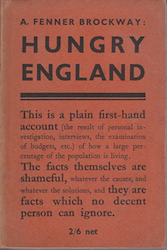

In 1980 Fenner Brockway was asked what had made him a socialist. In his reply, the former journalist and ILPer referred to an eye-opening tour of Britain’s deprived communities that he made in 1932 and wrote about in a book called Hungry England, published a full five years before George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier.

What he witnessed was hidden poverty and a depth of malnutrition that stretched from the mining towns of Wales to the shipbuilding communities of Tyneside, the industrial settlements of the Black Country and the rural villages of Norfolk.

What he witnessed was hidden poverty and a depth of malnutrition that stretched from the mining towns of Wales to the shipbuilding communities of Tyneside, the industrial settlements of the Black Country and the rural villages of Norfolk.

“I came, as a young journalist, to London, and lived in a settlement in Islington. It was the appalling poverty of the people,” recalled Brockway of his socialist awakening in the early 1900s. “Most of the workers, casual workers, were out of work for half the week. No unemployment benefits. Only the workhouse. There was literal starvation in their families. Children used to be coming to school hungry, every day.

“There has been a social revolution, not a socialist revolution, since those days… In the 1930s I did a survey of this country. I could only call my report, Hungry England. There was literally hunger. There is poverty today. Unemployment today. But we don’t have hunger marches of the unemployed.”

More than 40 years on, that “social revolution” appears to be in tatters as a decade of austerity and the cost of living crisis threaten to bring 1930s-style hunger back to the homes and communities of Britain.

The figures are stark. The NHS reports that cases of malnutrition, scurvy and rickets have all doubled in a decade. Foodbanks have grown exponentially, yet people can no longer afford to heat their food. Last month the Resolution Foundation warned the prime minister that half a million children would fall into poverty over the next year. “A hungry child can’t learn,” it said.

Desperate plight

Brockway’s Hungry England is not an easy book to read in 2022, simply because the picture it describes is so uniform and repetitive. Wherever Brockway went, he encountered the same desperate plight among those struggling to find work due to the depression.

In Lancashire he wrote of the picturesque moors between the higgledy-piggledy towns of Burnley, Blackburn and Nelson, each reliant on mills that now stood idle. In Great Harwood, he described the outward respectability of the houses masking the poverty inside. As many as 74% of the workers were unemployed, he wrote. “They can buy neither clothes nor boots, nor enough food for their children. The cheapest of everything has to be bought; anything, so long as it can be eaten… Multiple shops have invaded the town with cheap, shoddy goods.”

In Lancashire he wrote of the picturesque moors between the higgledy-piggledy towns of Burnley, Blackburn and Nelson, each reliant on mills that now stood idle. In Great Harwood, he described the outward respectability of the houses masking the poverty inside. As many as 74% of the workers were unemployed, he wrote. “They can buy neither clothes nor boots, nor enough food for their children. The cheapest of everything has to be bought; anything, so long as it can be eaten… Multiple shops have invaded the town with cheap, shoddy goods.”

In Birmingham, houses which had the look of “a district devastated by war … houses in ruins, with bricks scattered in confusion … cracked walls and roofs… So looked the towns of Flanders before they were repaired.”

The beauty of the Norfolk countryside also disguised great hunger, while the poverty in South Wales meant many young girls were too weak from malnutrition to be accepted into work.

Brockway described a train trip to Glasgow during which he examined news reports of the suicides among unemployed men. John Johnson, aged 53, an unemployed chemist, of Warwick Road, Stratford, found dead in a field with throat and wrist wounds after three months of unemployment. His note reads: “I am not destitute and have no grudge against anybody. Loss of work and the vision of impending poverty of those near and dear to me has preyed upon my mind.”

Arthur Taylor, an unemployed engineer, of Dawson Road, Handsworth, Birmingham, found dead in the Birmingham canal. His widow said he had become very nervous and depressed due to being out of work, while his health had declined since hearing he had to appear before a means test committee.

Brockway’s conclusions are brief. Actual hunger existed widely across Britain, he said, in the sense that people’s nourishment was less than enough to maintain bodily health. Wages were often too low to provide the elementary needs of human life. A large percentage of working class children were growing up under-nourished, ill-clad, and ill-shod, with disastrous results for the next generation.

Even employed workers were unable to save due to their high bills, while full unemployment benefit could not provide most families with their barest needs, so large sections of the unemployed were buying food of the poorest quality without the elements necessary for health.

In closing, he wrote that his purpose had been to describe rather than diagnose. “But… I ask them [my readers] to consider whether something is not fundamentally wrong with a civilisation which, despite its almost magical possibilities of wealth production, leaves masses of the population in the state of destitution that I have found. Is it not time we decided to build a new civilisation in which these possibilities shall be used to feed and clothe and house our people, and to liberate their minds and personalities to the full potentialities of human knowledge and experience?”

Reviews of Hungry England are not easy to come by. The Spectator was a notable exception, but tried to frame the circumstances Brockway had uncovered as an overall improvement on conditions among previous generations.

One person who was greatly affected by Brockway’s account of Great Harwood was the Reverend Roger B Lloyd, who tracked down the families featured in the chapter on the town and visited them all, learning that Brockway “had not exaggerated in the least”. He asked readers of the Manchester Guardian to offer help and, following some generous donations, was able to start occupation centres, allotments, physical training classes and organised games.

However, the book was not always appreciated by those living in the towns he visited. In 1944 Brockway travelled to Bilston to speak on behalf of Arthur Eaton, the ILP’s parliamentary candidate in a by-election following the death of the sitting Conservative. He found he was not welcome because he had described the town as ugly, and Hungry England had been banned from all the local libraries as a result.

Intense debate

The biggest impact of the book is perhaps a coincidental one for in February 1933 the editors of the Week-end Review published a letter under the title ‘Hungry England’. Of course, we cannot prove they had Brockway’s book in mind, although he had written for the Review in 1930 when he expressed his displeasure at the inability of the second Labour government to put forward an ambitious programme of “bold social legislation” to control rents and prices of the necessaries of life, and to introduce measures to lift the unemployed above “semi-starvation level”.

The letter in question was written by Vera Meynall, who raised the tragic case of Annie Weaving, a 37-year-old woman who starved herself to death to feed her children. “It is difficult for those of us who, by good luck, have always been able to take meat, vegetables and pudding for granted, to realise the full horror of this story,” she wrote. “This family was receiving the maximum reliefs and allowances to which they were legally entitled; and still, in the opinion of a representative of the law, it was not enough to keep them all alive…

The letter in question was written by Vera Meynall, who raised the tragic case of Annie Weaving, a 37-year-old woman who starved herself to death to feed her children. “It is difficult for those of us who, by good luck, have always been able to take meat, vegetables and pudding for granted, to realise the full horror of this story,” she wrote. “This family was receiving the maximum reliefs and allowances to which they were legally entitled; and still, in the opinion of a representative of the law, it was not enough to keep them all alive…

“This is not an isolated case, a hard luck story… It might happen to any one of the millions of unemployed families who are existing just on the borderline of starvation. It should in fact, explode the comfortable but superannuated belief of the tax-paying classes that no-one need starve in England.”

The letter set in motion a debate of an intensity never repeated in the pages of the short-lived Review. JC Pringle, secretary of the Charity Organisation Society, stated his commitment to supporting “the hard cases” and sympathetically studying their particular problems and troubles, yet pointed out that ‘the dole’ was more generous than it had been a decade before.

In his response, Labour MP George Lansbury countered that “the warehouses of the country are full of goods; there is an abundant labour power to produce and ever-increasing abundance”. The world was suffering “not from a lack of goods but a lack of brain power to provide a scheme” for their distribution. The idea that people should go without in a society of such abundance was not a Christian nation, he claimed.

Echoing some of the Spectator’s attitude, a Godfrey Elton wrote that he had visited many homes of the unemployed but never seen real hunger.

“There may be real hunger, although the medical officer of an industrial area, as hard hit by unemployment as any in the kingdom, informed me that he has met no instance of disease due to under-nourishment and that the marked majority of cases to which he is called amongst the unemployed arise from indigestion due to normal eating combined with the loss of normal physical exercise. There may be real hunger, although having starved myself, I know what no ‘hunger marcher’ can really be hungry, for the simple reason that no really hungry man can march.”

In response to Elton, EC York of New College Oxford retorted. “Has he ever read Fenner Brockway’s Hungry England? And if so, what does he make of it? Does he believe it to be a substantially correct statement of facts, or a tissue of lies?”

Once again, Hungry England?

The strength and volume of letters, many of which went unpublished, prompted the editors of the Review to commission their own fact-finding committee, which included in its number VH Mottram, a member of the Ministry of Food’s Advisory Committee on Nutrition. The aim of the report was to calculate exactly how much money was required of an individual to provide for himself and his family on unemployment benefits.

The committee concluded: “Those who, after reading this report, look back to the details of actual budgets given in the preceding correspondence will find that, at any rate in several instances, sufficient money to buy a minimum diet has now been allowed to destitute families by Public Assistance Committees or the State.”

In March 2022, Wolverhampton Council published its Financial Wellbeing Strategy 2022-2025: Tackling the Cost-of-Living Crisis. Bilston East was identified as one of the most deprived areas of the city.

“People are having to choose between heating and eating which is a sad fact but the increase in fuel bills is astronomic,” councillor Bhupinder Gakhal reported. “Countless more people … are too embarrassed to say they have cut themselves off [from fuel]… And it will not be just people who are on benefits, this is affecting working people.”

Ninety years after the publication of Hungry England, the malnutrition Brockway believed had been done away with, is returning to Britain. With the end of the war in Ukraine not yet in sight, and a further increase in utility bills expected later this year, it is only a matter of time before a journalist – perhaps The Guardian’s John Harris – reports on the growing hunger of the nation today, perhaps even in the same places Brockway visited decades ago.

It is important to state that a reported 40% of Universal Credit claimants are in work. And this year, the government aims to transfer up to 1.7 million legacy benefit claimants onto UC, people who will then face a five-week wait for money.

Without government intervention, another hungry England is surely upon us.

—-

Christopher Olewicz is a historian and director of Principle 5: Yorkshire Co-operative Resource Centre based in Sheffield.

You can read Fenner Brockway’s Hungry England here.

See also: ‘Brockway’s Book & the Post-Covid Search for a Utopian Future’ by Christopher Olewicz.

18 April 2022

What now? Not much chance of the government returning to the system of social benefits developed during the late 1940s and maintained by political consensus for more than three decades.

There are fewer proper jobs available now, with highly developed technology and a hyper-commercialised economy. The time is right for more localised initiatives – taking control of local economies. The community wealth-building schemes in Preston, Islington and other places are impressive. Sheffield was a forerunner of this kind of approach in the 1980s.

Perhaps it is time for local authorities to work with those economic drivers, sometimes known as ‘anchor institutions’, which control such a big part of local economies – universities, hospitals, etc – and make money work for the benefit of local communities.

Community collaboration and organisation might be a helpful strategy. For example, the cooperative town idea.