MARY STRATFORD celebrates the return of Durham Miners’ Gala, explaining how it’s survived for more than 150 years and why it still matters to local people and the wider Labour movement.

The Durham Miners’ Gala returns on 9 July after a three-year hiatus due to the pandemic. The 136th edition of this annual celebration of the mining communities will see upwards of 200,000 people throng the historic roads and bridges of this small north-east city as they once again fill with flying banners and resound to the sound of brass bands.

Given that the last deep mine in County Durham closed in 1993, the continued survival and increasing popularity of the event known to locals as ‘the big meeting’ is all the more remarkable.

Given that the last deep mine in County Durham closed in 1993, the continued survival and increasing popularity of the event known to locals as ‘the big meeting’ is all the more remarkable.

Born in 1871 out of a desire to demonstrate the strength of the newly formed Durham Miners’ Association, the Gala gained political importance in the area as the union’s influence on local politics grew and the Labour Party began to replace Liberals in positions of power across the region.

The union’s early leaders soon recognised that a coming together of their numerous lodges would reinforce a sense of collective identity and shared values, and give families and friends otherwise dispersed across a largely rural county, a chance to put on their Sunday best and experience a great day out. It is that sense of shared experience and celebration that makes the Gala such a unique Labour movement event, even today.

The expansion of the Gala was rapid and it wasn’t long before national and international political figures graced the platform, giving speeches that reflected the broad church of the Labour movement. From the revolutionary to the reformist, all wings were represented, often by some of the movement’s most notable and controversial political figures, not least Annie Besant, Prince Kropotkin, Tom Mann, Keir Hardie, Jimmy Maxton, AJ Cook (who in 1927 spoke alongside Oswald Mosley), Ramsay MacDonald, Ellen Wilkinson, Clem Attlee, Aneurin Bevan, Jennie Lee, Barbara Castle and Harold Wilson.

The leadership of the DMA was firmly aligned to the reformist tradition and there was often a tension with Durham’s more radical ‘red lodges’, which could be unimpressed by the invited ‘moderates’. Indeed, following the election of the post-war Labour government, it was unheard of for a Labour Party leader not to grace the Gala with his presence, a tradition ended during Tony Blair’s leadership (despite the Durham native representing a County Durham constituency).

In recent decades the Gala has tended to invite speakers from the left, including regulars such as Tony Benn and Dennis Skinner, while Jeremy Corbyn also appeared during his campaign for the Labour leadership in 2015.

Cultural renewal

So what is it that makes this event so special to the people of County Durham and increasingly now to those in the Labour movement across the country? Why has Durham’s Gala not only survived but thrived (despite the reluctance of Labour leaders to grace us with their presence), while those in other coalfields have faded away?

The first thing to acknowledge is that it didn’t happen by accident and credit must go to the leaders of the DMA in 1993, general secretary David Hopper and president David Guy, who recognised its cultural and political importance. The unlikely saviour of the event at this time was a wealthy New Zealand businessman, Michael Watts, who had links to the Durham coalfield and agreed to finance the event until 1999, giving the union welcome breathing space and time to find alternative sources of funding.

The first thing to acknowledge is that it didn’t happen by accident and credit must go to the leaders of the DMA in 1993, general secretary David Hopper and president David Guy, who recognised its cultural and political importance. The unlikely saviour of the event at this time was a wealthy New Zealand businessman, Michael Watts, who had links to the Durham coalfield and agreed to finance the event until 1999, giving the union welcome breathing space and time to find alternative sources of funding.

Attendances were dwindling throughout this period and for a while it seemed the Gala might cease to be viable. But a campaign was launched to save it and organisations such as the Co-op Party, other trade unions, local authorities and local communities joined together to ensure its future, while the National Lottery Heritage Fund became an unlikely ally.

The revival also had a cultural thread, started by chance in 1996 when one of the local villages accidentally damaged their lodge banner as they took it down, preparing to parade it through Durham for what they thought may be the last time. For one villager, the incident seemed to signify the death of her community, such was the perilous position of the Gala at that point.

In fact, the opposite occurred. Locals formed a group to raise funds for a new banner and approached the Lottery fund for help. As a result, a new banner was designed and commissioned by the community and, as is tradition, blessed in Durham Cathedral at the following year’s Gala.

This small act of renewal led to an explosion of banner groups around the county as former lodges raised funds to repair or commission new banners, even those like my own where the pit closed in 1965.

The new banners were designed by the communities themselves, often involving local schoolchildren. Some, including mine, produced a replica of the original banner. Others made new designs reflecting their changing communities. All marched proudly to Durham to see their banners paraded and blessed with a renewed sense of commitment to their villages and the Gala.

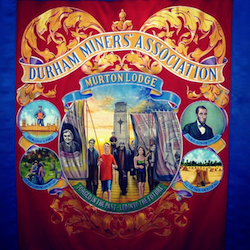

The banners themselves provide a rich social history of the values of Durham mining communities, from the formation of the union in 1869 onwards. Many of the earliest designs had used religious imagery to convey a union or socialist message. Others were avowedly political, featuring, among others, figures such as Marx, Lenin and Hardie.

In more recent years, other trade unions and political groups have begun to parade their own banners and bring their own bands. New groups have emerged, such as a women’s banner group who wanted to celebrate the specific contribution of women of the Durham coalfield. Their banner, displaying the green and purple colours of the women’s movement, will be blessed at this year’s cathedral service alongside five other new designs.

Festival spirit

In the 21st century, the Gala has continued to expand, to such an extent that the procession along the streets of Durham again takes several hours to weave its way to the racecourse for speeches. A key factor in its success has been the event’s ability to evolve in a changing world, and its desire to be inclusive – exemplified by the motto of the DMA: “The past we inherit, the future we build”.

While it remains an explicitly political event, the Gala has never only been that. From its early days, it was also part festival, part community gathering – a chance to meet-up with comrades and friends in celebration. For some, it’s about pride in a shared history and heritage, while for others it’s a chance to re-energise their politics, to hear speeches and highlight campaigns. It is also a time to reflect and remember the true price of coal.

While it remains an explicitly political event, the Gala has never only been that. From its early days, it was also part festival, part community gathering – a chance to meet-up with comrades and friends in celebration. For some, it’s about pride in a shared history and heritage, while for others it’s a chance to re-energise their politics, to hear speeches and highlight campaigns. It is also a time to reflect and remember the true price of coal.

This year, in a break with tradition, the event is dedicated to all those key workers who played (and still play) such a pivotal role during the pandemic. Speakers will come from the key worker unions, while there will also be rank and file workers marking their role in keeping us safe and the economy going during truly unprecedented times.

Whatever the Gala means to those attending, however, one thing’s for sure – it remains the greatest celebration of trade union and Labour movement values in the UK and, in my view, beyond. It is a demonstration of the power of collectivism and how solidarity can sustain and renew us. It reinforces why we are stronger united, and for that reason alone it is critical that it continues.

In 2015, a new group was formed to ensure the event’s survival, called the friends of the Durham Miners’ Gala, or ‘The Marras’. Please consider becoming a member and if you haven’t been to Durham Miners’ Gala, put it on your list. It is a day to remember and to celebrate. If you come once, you will come again.

—-

Mary Stratford is chair of Education4Action, a voluntary group based at the Durham Miners’ Hall on Redhills that seeks to educate people about the building’s political significance and promote the values of trade unionism.

More about this year’s Gala is here.

More about the history of the Durham miners’ banners is here.