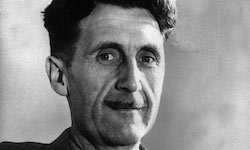

George Orwell’s celebrated book on the Spanish Civil War is often misinterpreted, says DANNY EVANS. It deserves to be read afresh without political blinkers.

George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia is the most famous book on the Spanish Civil War in the English language, but there is a tendency among both its admirers and detractors to misrepresent its contents. The former exaggerate the extent to which the book exposes Soviet skulduggery in Spain, the latter attempt to discredit Orwell as a witness and analyst.

Whatever Orwell’s personal and political failings, his 1938 account of his time in Spain is well worth reading both as a primary source and as an analysis of wartime Republican politics and policies. The purpose of this post is to encourage a reading of Homage to Catalonia without the distraction of misleading interpretations from expert commentators.

Whatever Orwell’s personal and political failings, his 1938 account of his time in Spain is well worth reading both as a primary source and as an analysis of wartime Republican politics and policies. The purpose of this post is to encourage a reading of Homage to Catalonia without the distraction of misleading interpretations from expert commentators.

Unless otherwise stated, page numbers cited below are taken from the Penguin edition of Homage to Catalonia published in 2001 as a part of the collection Orwell in Spain.

Misrepresentation 1: It gives the impression that the Spanish Republic lost the Civil War because of Stalin

Homage to Catalonia has been read this way primarily by anti-Stalinist admirers of Orwell. His detractors, likewise, have accepted this framing and used it as a stick with which to beat the book. It is not, however, an accurate reflection of its contents.

A significant motivation behind writing Homage to Catalonia was to counter the prevailing misrepresentations of the Spanish Civil War on the British left and in literary circles when it was taking place. Orwell was moved by the lies that the Stalinist press was telling about Spanish revolutionaries and, in particular, about the POUM, which were often repeated in more mainstream liberal publications.

There is a big difference, though, between pointing out that Communists were lying about the Civil War and claiming that Stalin was chiefly responsible for its outcome. Insofar as Orwell discusses the broader role of the Communist Party in Spain, he explains in cautious fashion how he changed his mind during his time in Spain, from an initial position in favour of the Communist line of ‘first win the war, then make the revolution’ to a belief that the determination of Communists (among others – as Orwell makes clear) to quash the revolution was itself detrimental to the war effort.

He concludes this discussion with the following lines: “I have given my reasons for thinking that the Communist anti-revolutionary policy was mistaken, but so far as its effect on the war goes I do not hope that my judgement is right. A thousand times I hope that it is wrong. I would wish to see this war won by any means whatever. And of course we cannot tell yet what may happen.” (p.189)

We should read these passages as an intervention in a debate taking place when the outcome of the war was uncertain. Presenting Homage to Catalonia as laying the blame for the Republic’s defeat on Stalin (who is mentioned only once in the book, in relation to a pamphlet found in Orwell’s hotel room) creates a handy straw man for the book’s detractors. The latter can then establish why Stalin was not to blame for the loss of the Civil War while ignoring the more awkward arguments made by Orwell for their reading of the conflict.

Misrepresentation 2: Orwell couldn’t speak Spanish

This common observation casts doubt on Orwell’s ability to understand his environment in Spain. In a recent interview with Alexei Sayle, Paul Preston suggests that Homage to Catalonia contains references to conversations that couldn’t have taken place.

In reality, Orwell spoke passable Spanish. By May 1937, he was in command of a section of 30 militia, a mixture of English and Spanish speakers. It is unlikely he would have been given this responsibility had he not attained a decent level of Spanish.

In reality, Orwell spoke passable Spanish. By May 1937, he was in command of a section of 30 militia, a mixture of English and Spanish speakers. It is unlikely he would have been given this responsibility had he not attained a decent level of Spanish.

That said, Homage to Catalonia doesn’t give the impression of his being able to converse easily with locals. Instead, Orwell repeatedly points out his difficulties in this area. He refers to his “bad Spanish” on the first page of the book. By contrast, John McNair, in Spain as a representative of the Independent Labour Party since the late summer of 1936, observed in his Spanish Diary (p.14) that Orwell had “fair Castilian” upon arrival in Barcelona.

In any case, the first few chapters of Homage to Catalonia establish both a basic level of knowledge and an eagerness to learn. More importantly, they demonstrate the lack of alternatives to trying to communicate, and therefore improving his level of understanding. Someone who, like Orwell, had a decent linguistic grounding and then spent months in close contact with Spanish speakers is likely to have made quick progress.

One searches in vain in Homage to Catalonia for an example of a conversation so complex that it would have required a masterful command of the language. Whenever such an occasion appears to come into view – for example, when Orwell is pleading the case of his arrested commander Georges Kopp – the author reminds us of how difficult his task was given his “villainous Spanish”. (p.160)

On the other hand, he also makes observations that are verifiably true and demonstrate a good linguistic level, such as remarking on the CNT’s (National Confederation of Labour) euphemistic treatment of the Spanish Communists as “a certain party” in its leaflets. (p.139)

On balance, it seems likely that both Orwell and his detractors have exaggerated his limitations in Spanish, and that these do not, in any case, serve to discredit the contents of Homage to Catalonia.

Misrepresentation 3: Orwell was just a front-line soldier who could not understand the ‘big picture’ of wartime Republican politics

As with the above case, this is another ad hominem criticism of Homage to Catalonia that avoids the need for either careful reading or engagement with its arguments. In a Guardian article publicising Giles Tremlett’s book about the International Brigades, Tremlett is reported as saying that Orwell “was unaware of how the murders of thousands of priests by the POUM’s anarchist allies (sic) had hurt the struggling Republic’s image, or how badly it needed the arms supplied by Stalin”.

Aside from being historically illiterate with regard to anti-clerical violence, it is hard to believe that anyone who had read Homage to Catalonia could come away with this impression. Orwell mentions the atrocity stories carried by the right-wing press in England intended to discredit the Republic more than once (p.171; p.185) and comments on the Republic’s need for effective weaponry with a regularity bordering on the tedious.

Aside from being historically illiterate with regard to anti-clerical violence, it is hard to believe that anyone who had read Homage to Catalonia could come away with this impression. Orwell mentions the atrocity stories carried by the right-wing press in England intended to discredit the Republic more than once (p.171; p.185) and comments on the Republic’s need for effective weaponry with a regularity bordering on the tedious.

The broader claim made by Tremlett, that “Orwell was just a frontline soldier. He didn’t properly understand how both the POUM and their anarchist friends were harming the fight against Franco” chimes with claims made by professional historians of the Civil War, but is no more justifiable. In fact, Orwell provides a balanced exposition of the case against the revolution within the Republican territory, most succinctly in his summary of the PSUC (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia) line on p.180.

It is essential to his narrative that he do so because he wants to explain to the reader (who he assumes will share this perspective) how he came to be dissuaded from this position himself. As with misrepresentation 1 above, historians would much rather discredit a straw Orwell than engage with the rationale he provides for changing his position.

Misrepresentation 4: Orwell was convinced of Communist responsibility for the Barcelona May days

This misleading claim is made by the late Christopher Hitchens in the introduction to Orwell in Spain. According to Hitchens, Orwell “became convinced that he had been the spectator of a full-blown Stalinist putsch, complete with rigged evidence, false allegation and an ulterior hand directed by Moscow” (p.xi).

This reading of the May days is a mere inversion of the conspiratorial fabrications with which Stalinists sought to pin blame on the POUM for the events. It is fantastical to claim that a general strike and uprising involving thousands of anarchist workers could have been plotted by either the leadership of the Soviet Union or the POUM.

In Homage to Catalonia, Orwell makes a mockery of such readings. He devotes a chapter to the contributory factors leading up to the events, commenting on food scarcity, political rivalries, and assassinations as creating heightened tension in Barcelona (pp.98-103). This narrative, in its essentials, differs little from that provided by mainstream historians such as Helen Graham.

When it comes to the specific causes and dynamics of the May fighting, Orwell’s comments amount to an explicit contradiction of the claim in Hitchens’ introduction. He notes: “The general attitude was: ‘This is only a dust-up between the Anarchists and the police – it doesn’t mean anything.’ In spite of the extent of the fighting and the number of casualties I believe this was nearer the truth than the official version which represented the affair as a planned rising.” (p.115)

More explicitly still:

“If it was not an Anarchist coup d’état, was it perhaps a Communist coup d’état – a planned effort to smash the power of the CNT at one blow? I do not believe it was, though certain things might lead one to suspect it… Presumably those responsible for the seizure of the Telephone Exchange expected trouble – though not on the scale that actually happened – and had made ready to meet it. But it does not follow that they were planning a general attack on the CNT. There are two reasons why I do not believe that either side had made preparations for large-scale fighting:

“(i) Neither side had brought troops to Barcelona beforehand. The fighting was only between those who were in Barcelona already, mainly civilians and police.

“(ii) The food ran short almost immediately. Anyone who has served in Spain knows that the one operation of war that Spaniards really perform really well is that of feeding their troops. It is most unlikely that if either side had contemplated a week or two of street fighting and a general strike they would not have stored food beforehand.” (pp.195-196)

Orwell’s champions do him a disservice by reducing his arguments to a conspiratorial caricature reminiscent of Cold War-era propaganda – not least because this allows his detractors to demolish an argument he did not make rather than address one he did.

Misrepresentation 5: Orwell misunderstood the case of Antonio Martín

Antonio Martín was an influential CNT activist in Puigcerdá, a Catalan town close to the French border. He was murdered in an ambush in April 1937. He was subsequently portrayed as a violent ‘uncontrollable’ terrorising the region, although this has been thoroughly debunked.

Orwell’s reference to this case says only: “A band of Carabineros were sent to seize the Customs Office, previously controlled by Anarchists, and Antonio Martín, a well-known Anarchist, was killed.” (p.102)

He mentions the episode in passing as a contributory factor to the growing tension in Barcelona. In this he is accurate, albeit that the details of who killed Martín are more complex than Orwell could have known and have only recently been clarified by the historians Agustín Guillamón and Antonio Gascón.

There is no sense in which Orwell “accepts the anarchist version that portrayed Martín as a martyr murdered by forces of the Generalitat”, as claimed by Paul Preston. This is not least because there was no such anarchist portrayal of Martín that might have been available to Orwell in 1937.

In fact, while the CNT leadership was happy to beatify Buenaventura Durruti, killed near the front in November 1936, in the spring of 1937 it actively discouraged the public commemoration of anarchists killed by political rivals in the rearguard. The report on the death of Martín in the CNT newspaper Solidaridad Obrera was brief, avoided mention of who killed him, and was accompanied by calls for calm and unity. (29 April 1937, p.12)

—-

Danny Evans is a historian based at Liverpool Hope University.

He would like to acknowledge Matt Cribbin’s undergraduate dissertation about Homage to Catalonia as historical evidence, an influence and inspiration for this piece.

This article was first published on the Anarchist Bookclub Newsletter and is reproduced with permission of the author.

See also: ‘The ILP, POUM and the May Days of the Spanish Civil War’ by David Connolly, and ‘Orwell and the ILP’ by Benedict Cooper.