Keir Hardie’s conception of Labour as a broad alliance of left and liberal thinkers is under threat like never before from Keir Starmer’s leadership team. DAVID CONNOLLY calls for a halt to the current hostility and a renewed commitment to the founder’s vision.

This is a tough time for the Labour left. When Keir Starmer was elected leader of the party three years ago (on 4 April 2020) he did so with the votes of many left wingers, including me, who saw his ‘Ten Pledges’ as the best we could achieve in difficult circumstances.

In the current issue of Renewal Martin O’Neil describes it as “de facto Corbynism without Corbyn” and “a way of keeping the radical energy of the Corbyn era while avoiding its shortcomings”.

In the current issue of Renewal Martin O’Neil describes it as “de facto Corbynism without Corbyn” and “a way of keeping the radical energy of the Corbyn era while avoiding its shortcomings”.

The pledges included specific policies to increase income tax for the top five per cent of earners; abolition of university tuition fees; common ownership of rail, mail, energy and water; strengthened workers’ right; and a commitment to “unite our party” and, ironically, “promote pluralism” within it.

But, as O’Neil notes, “Starmer as leader has been a very different creature to the Starmer who had been looking for the votes of Labour Party members.”

Following the disastrous Hartlepool by-election in May 2021, and subsequent public advice from Tony Blair (in the New Statesman) and Peter Mandelson (in the Guardian), Starmer changed course. The route to electoral success is now being driven through a much more centrist politics allayed to a sustained attack on the Labour left.

This has included:

- withdrawing some key promises made in his leadership campaign on taxation, tuition fees, common ownership and EU voting rights

- widespread use of unfair and undemocratic ‘retrospective expulsions’ whereby members are expelled for supporting procribed organisations when, at the time, it was legitimate to do so

- cynical manipulation of the parliamentary selection process to exclude left candidates from longlists to the extent that the respected journalist, Michael Crick, has suggested a young Robin Cook would not have been accepted as a candidate these days

- “weaponisation” of allegations of anti-semitism in pursuit of factional ends, as Martin Forde KC put it

- removing the whip from Jeremy Corbyn and passing a motion at the NEC banning him from standing as Labour parliamentary candidate, supposedly to signal to red wall voters that the demonised former leader is now effectively banished from the party altogether.

Discouraged and consciously alienated by the leadership, it’s estimated that 90,000 members left the party in 2021 alone, which of course only makes it easier for the right to consolidate its grip on the NEC.

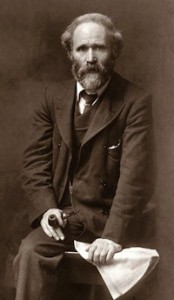

So Labour’s historic ‘broad church’, originally conceived by Keir Hardie after he lost his seat in West Ham South in 1895, an alliance that’s always been a mixture of liberal and socialist thinking, is under threat like never before.

Left commitments

Despite all that, and the leadership’s move to the political centre, there are still some important Labour commitments the left can support, including:

- to spend £28 billion a year of capital on the green transition

- to ensure all workers are entitled to sick pay, paid holidays and parental leave from day one

- to create a framework for fair pay agreements

- to ban zero-hours contracts and bogus self-employment

- to overhaul the British constitution and make the House of Lords an elected second chamber of the nations and regions, as recommended by Gordon Brown’s Commission on the UK’s future.

After 14 years of Tory rule, such is the deep and pervasive dysfunctionality of our social state that any Labour government would face a daunting challenge to meet the needs and expectations of the people.

Given the problematic state of the government’s finances, plus a global environment likely to be even more chaotic than it is now, quite how long the leadership can sustain its commitment to social justice without a major redistribution of wealth to society’s poor and disavantaged remains to be seen.

Given the problematic state of the government’s finances, plus a global environment likely to be even more chaotic than it is now, quite how long the leadership can sustain its commitment to social justice without a major redistribution of wealth to society’s poor and disavantaged remains to be seen.

In the meantime, the Labour left needs to remain in the party to defend the notion of Labour as a tolerant and respectful broad church, and to claim its own legitimate place within it.

Starmer recently told his party critics that if they don’t like what he is doing they know where the door is – a regrettable and unnecessary insult to thousands of activists who have sustained Labour through thick and thin over the years.

It is a great shame that Labour’s internal politics has descended to this level. Since it rejoined the party in 1975, the ILP has consistently argued for Labour to be, in the words our political perspective, “an active, participatory, membership-based democracy that welcomes the co-existence of different viewpoints and upholds principles of pluralism, mutual respect and comradeship”.

The statement goes on: “The extent to which Labour can realise its radical potential will depend on the strength and depth of its internal democracy, on the forces and movements that align with it, and on the political space they can open up together.”

In short, Hardie’s broad church is Labour’s strength, both internally and as a political force. It will always have its right; it will always need its left. The ILP, for one, isn’t going anywhere. After all, it’s our party as well. We were there at its birth.

—-

David Connolly is chair of the ILP.

See also: ‘Safety First: Keir Starmer & The Road Ahead’ by David Connolly.

16 May 2023

I would echo much of what Ben has said. I don’t want New Labour, but I don’t want the People’s Front of Judea either. I am with the left on policy but far too many of them are bitter, far too quick to scream ‘traitor!’ and have absolutely no idea whatsoever how to engage with ordinary voters.

I was much influenced by Eric Preston’s 1982 pamphlet Labour In Crisis, much of which is still relevant. We have not grasped that those born the year Thatcher came to power are now 44 and may even be grandparents.

Fourteen years working in a supermarket have shown me that the Thatcherite taxpayers’-money-benefit-scroungers-immigrants worldview is now normative. We are not providing an alternative narrative – that ‘human nature’ is as co-operative as it is competitive (Bevan); that many services are better provided publicly; that tax is both an investment in our country and a civic duty.

We have Starmer for the foreseeable future. We have to stand up for the gentle, libertarian, humane, democratic socialism that is the inheritance of the ILP. He may not like it.

12 April 2023

Ironically, this article re-enacts what Martin Forde QC meant when he criticised the factional use of anti-Semitism under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. If you follow the links in the text, rather than rely on the misleading reference in the main article to the Forde report, it says: “Mr Forde’s report says factionalism was ‘endemic’ within Labour and the issue of anti-Semitism was weaponised by both sides, not just the party’s right.”

Starmer’s approach to anti-Semitism after the period covered by the Forde report has been driven by the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s statutory investigation, which placed legal obligations on the party to respond comprehensively to its recommendations. His actions as leader should be understood in light of those obligations.

I am deeply uncomfortale with Starmer’s leadership of the party, not just in relation to internal party democracy but also in relation to economic policy (although, as a lawyer, I wasn’t surprised he hasn’t followed his ten ‘pledges’, as they had more loopholes than a knitted woolly and I didn’t vote for him to be leader as a result).

I am also uncomfortable with the left’s lack of ability to grapple with anti-Semitism and Jeremy Corbyn’s huge mishandling of the issue during his leadership and subsequently. I will stop short of explaining why I feel both dismay and disgust at his current grandstanding and self-fulfilling victimhood. It only serves to underline the irrelevance and cultishness of the left and its lack of purpose.