Digging through family history, RAYMOND SWEETMAN uncovered the story of his great uncle – an ILP pioneer and ‘middle ranking’ socialist whose long-lost tale deserves to be told.

Septimus Henry Sweetman was an eminent local politician in east London and a community worker throughout his life, one that straddled the 19th and 20th centuries from 1857 to 1934 (see gravestone below). He was also one of the ILP’s pioneers, a founder member and one its earliest election candidates whose political contribution and achievements have long been lost from the pages of Labour history.

Like thousands of others, he was among the ‘middle ranks’, representing a stratum of the early labour movement that is has not been well documented – one of those who were neither high-profile, such as Keir Hardie, who have been covered in great detail, nor mere members, who associated with the cause simply by paying their monthly subscriptions.

Like thousands of others, he was among the ‘middle ranks’, representing a stratum of the early labour movement that is has not been well documented – one of those who were neither high-profile, such as Keir Hardie, who have been covered in great detail, nor mere members, who associated with the cause simply by paying their monthly subscriptions.

He was, like many others, active in numerous organisations – an ILPer from its birth, he also played prominent roles in the local Clarion Cycling Club, with Christian socialist associations, in the Hearts of Oak Friendly Society and with a number of other political and community-orientated groups. What’s more, he was a notable speaker, sharing platforms with national figures such as Hardie, and a regular writer in the national and local press as well as for labour movement publications such as The Clarion, Labour Leader and others.

So how and why has he been forgotten? And how did I come across him?

The second question is easier to answer, for Septimus is my great uncle and I became fascinated with his story while researching my family history, so much so that I am hoping to use the wealth of material I have since complied to write a biography.

In learning about his life, what struck me sharply was the sense of someone, unknown even to family members, who gave much of his life to the movement for little recognition, and did so as an active member of different organisations at the same time, rather than being single-mindedly, or ‘factionally’, dedicated to one or the other.

This chimed with a quote I uncovered from David Marquand who wrote: “In fact, it is almost impossible to categorise trade union leaders in the 1900s neatly under self-contained labels such as Lib-Lab or socialist, let alone Fabian, Marxist or ILP member. Many could be described at different or even the same time as eclectic believers in a wide range of often contradictory political positions within an ill-defined progressivism.”

As ever with research on local Labour figures, the absence of surviving printed ephemera, such as membership cards, minutes or indexes, means I have had to rely on other printed sources, such as local newspapers, to determine dates, events and affiliations.

Inevitably, there are gaps. Yet I hope this brief profile provides a flavour of a man who played a not inconsiderable role in growing the ILP and the wider socialist movement during its crucial early years.

Sorting boy to socialist

Septimus was born on 4 March 1857 at 12 Lascelles Place, St. Giles, Middlesex (now London), although the family address at that time was 70 Chapel Street. His father was George Milton Sweetman, a furniture japanner and his mother Ann Sweetman (née Davison). Septimus had six brothers, two of whom died as infants while the other four survived into adulthood.

He started work as a boy sorter for the General Post Office (GPO) on 3 October 1871 and spent the rest of his working life at the GPO, rising to the senior rank of superintendent before retiring in 1920. Politically, he started out as a Liberal and was the secretary of the Marylebone Young Men’s Liberal Association.

The first record of Septimus’s involvement in the labour movement comes in 1893, the year the ILP was founded, when he spoke at a public debate entitled ‘Socialism and Christianity’ at the Field Road Chapel in Forest Gate, east London. In the years that followed, he became a regular speaker and debater at events all over the country while also being a branch secretary of the Clarion, a member of Christian socialist groups and the Hearts of Oak.

In October 1894, Septimus stood for election to West Ham council as the Socialist Labour candidate for the Forest Gate ward. According to the West Ham & South Essex Mail the Socialist Labour council was made up of an alliance between the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the ILP, plus members of local trades councils. Septimus was easily defeated, placing fifth out of seven candidates.

In March 1895, he wrote an extended essay entitled ‘The Unity of Socialism’ in The Clarion, which gives a strong sense of his ecumenical approach to socialism, and his aversion to any hint of factionalism.

“The watchwords of Socialism which attracted me to the movement were association, fraternity and goodwill,” he writes. “I fondly thought that at last there were being formed societies of men who desired to realise the dreams of reformers, and that we should soon be enabled to view the promised land, and perchance walk therein.

“The dissents which had hitherto torn sects and creeds, and the crafty subtle ties of party politics, I thought, would not, could not, enter and mar the good work these men and women, who had placed before them a high ideal of human happiness, intended to do. Individual party prejudices and the egotism of readers were to be the things of the past, in view of the necessity for combination, in order to attain the better life we all wished for.

“Alas, for human hopes! As one of the rank-and-file, I am positively dismayed at the elements of disintegration at work within Socialist societies of today. I find that instead of harmony and goodwill existing between the ‘officials’ of the different organisations, they are at daggers drawn, and the swords which should be turned towards landlordism and capitalism are being used for the fatal purpose of internecine strife.

“The Social Democratic Federation will have no other Socialism, unless it bears their mark of purity. The Independent Labour Party believes in none other than itself. It scorns Fabians and condemns Christian Socialists as being but allies of the enemy, and the Municipal Socialism of the London County Council has drawn upon itself the destructive lightening of the London Conference of two-score delegates!

“I strongly condemn the leaders of the Socialist organisations for this policy of isolation. The majority of the mass members do not desire it I feel certain; and the sooner some understanding is arrived at for common action, the better for Socialism and the good of the people.”

Clearly, Septimus was very active during this period for the following month he chaired a meeting addressed by the ILP, and in March 1896 was present as an entertainer when Hardie opened an ILP club at Canning Town, the West Ham & South Essex Mail reporting that: “The performance of SH Sweetman’s Socialist String Band was a surprise to many people who came from a distance.”

He was alongside Hardie earlier that year too, when the ILP leader spoke at Stratford Town Hall. His wife, Alice Martha, was beside him on stage, according to the Mail, which reported a very large crowd and a rendition of ‘England, Arise!’ to open the meeting.

“We often hear about the desirability for one Socialist party, and there are those amongst you who know that there is but one Socialist party, and cannot be two,” said Hardie, while Septimus “demanded that common honesty should rule between men”.

“They were asking for a merrie England, a just and happy England,” he said. “In West Ham they attempted to make some attempt to put Socialism into practice. They were getting more Socialists onto public bodies [cheers] and they would demand that each man should have a chance to live a happier and better life.

“He was told that the London and India Docks Joint Committee were refusing to employ men who would not drop their membership of the Hearts of Oak Benefit Society, or the Foresters, or Oddfellows, and join a fund run, offered and managed by the Joint Committee. The object of that was plainly to rob the men of all power to take any independent action.”

Against the grain

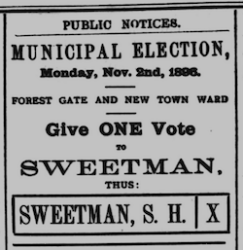

There is little doubting Septimus’s political ambition at the time for he stood for council again in 1896, 1897 and 1898, placing fifth, sixth and third respectively in West Ham’s Forest Gate ward, in the last case only just missing out on election by 24 votes.

This result appears to have been Septimus’s best ever performance at an election, and a creditable result for a man of the left. The London County Council elections, just eight months earlier, were said by Richard Heffernan (in Brian Brivati and Richard Heffernan’s The Labour Party: A Centenary History) to have shown no indication of “the growth of public sympathy towards avowed Socialism in London… Had a number of candidates been put forward with a programme in favour of devastating London with cholera, they would probably have received no less support.”

This result appears to have been Septimus’s best ever performance at an election, and a creditable result for a man of the left. The London County Council elections, just eight months earlier, were said by Richard Heffernan (in Brian Brivati and Richard Heffernan’s The Labour Party: A Centenary History) to have shown no indication of “the growth of public sympathy towards avowed Socialism in London… Had a number of candidates been put forward with a programme in favour of devastating London with cholera, they would probably have received no less support.”

In this context, the result Septimus achieved seems to have gone against the grain and he was suitably grateful, issuing a rousing thank you statement to those members of the electorate who voted for the Socialist Labour programme.

“You are not all Socialists, therefore your confidence in an avowed Socialist Labour candidate is the more remarkable,” he said. “The vote given by Forest Gate for the Socialist Labour programme, though unsuccessful, was higher than the same vote in Canning Town or Stratford.

“This result is extremely gratifying and cheering; it shows that prejudice is disappearing and that the genuine, honest, industrious and intelligent workman is beginning to lose faith in renegade Liberalism and shabby-genteel Conservatism, and is at last coming round to our view that the only road to the salvation of the people is Socialism – ie. the united action of the community for the common good of all.

“Our principal opponent was aided by a rare combination of the Tories, Liberals who have shed their faith, teetotal crusaders, publicans, non-conformist ministers, and all the vested self-interests combined. They only won after strenuous exertion. Their doom is already written on the wall.

“Personally I prefer defeat with the 1,184 votes for social salvation of the people than victory with 1,490 votes given for bolstering up the old policy of dirt, degradation, disease, rack-renting and sweating.

“Workers, you will win. You must awake from your apathy and use your strength. We shall go organizing, agitating, and educating for victory. Socialism is never defeated. It is only delayed.”

He may not have been successful as a candidate but Septimus’s activism was undimmed as he appears regularly in the pages of a range of east London and Essex newspapers over the following years, commenting on topics such as the rates, health and education. In 1906, he contributed an article on poverty in the Essex rural area to a prominent book edited by H Rider Haggard, and between 1907 and 1910 the Labour Leader regularly listed Septimus as a donator to electoral funds and other appeals.

Community servant

By 1910, however, he appears to have moved away from east London, heading south west across the capital to Wimbledon. Something of his dedication and standing locally can be gleaned from how this news was reported in the Eastern Counties Times:

“Many Ilfordians will learn with considerable regret of the removal of Mr SH Sweetman from Ilford to Wimbledon,” it says. “Mr Sweetman has taken an active part in local affairs for years past, and will be greatly missed. In the promotion of the University Extension lectures in the town and of higher education among the working classes, and in all matters in which the interests of ratepayers and residents were at stake, his voice and his pen were ever at the service of the community.”

From then on, Septimus seems to have had less involvement in the ILP and the labour movement more widely. During World War One he was a local official for south west London branches of the Patriotic Association and the British Red Cross. The former was a coalition of individuals and local businesses that organised gifts and food parcels to be sent to British servicemen held as prisoners of war by the Germans. As there was no contact between the British and German governments, these voluntary associations helped eased the suffering of POWs.

Alice died in 1919, and in 1920 Septimus retired from the GPO and moved to Worthing where he spent the rest of his life. It is clear from his surviving writings that during the Great War period he had started to move away from active involvement in socialist politics. Instead, he and his second wife, Louisa Victoria, threw themselves into a range of local community work and independent politics.

Louisa died in 1932 and his final weeks were spent in Kingston, south west London at the home of one of his daughters, Ruby Rose Milton Sweetman. He passed away on 17 April 1934 after a short illness, aged 77.

So what are we to make of these glimpses of an ILP activist and early agitator for socialism?

Of course, it’s difficult to generalise. If nothing else, however, his wide range of memberships, his persistent election candidacies, his advocacy and community work, and the local political involvement he showed throughout his life seems to confirm the belief of Marquand that the labour movement at the time was made up of ‘eclectic believers’.

My great uncle Septimus, it seems, was one of them, a ‘middle ranker’ whose tale deserves to be told.

—-

Raymond Sweetman is looking for more information about Septimus Sweetman and other members of his family:

- Frederick Sweetman – Labour prospective parliamentary candidate, Chatham constituency, 1940

- Arthur Milton Sweetman – decorated WWI infantryman, WWII ARP organiser and Labour candidate in the borough of Battersea elections during the 1930s

- Thomas George Sweetman – decorated Boer War veteran and trade unionist in the furniture trade, 1900s to early 1930s.

He is also searching for a photograph of Septimus. “None have been passed down through the family and none have been recovered during the extensive research process,” he says. “I hope this article may reach other researchers who have identified him in photographs.”

Raymond can be contacted directly by email: purpleakpop@gmail.com

You can read more ILP profiles here.

Photo credits:

Septimus Sweetman’s gravestone in Broadwater Cemetery, Worthing: © Raymond Sweetman

Electoral advertisement for the candidacy of Septimus Sweetman from the Saturday 31 October 1896 edition of the West Ham & South Essex Mail: © The British Library Board. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive