For KATH CONNOLLY, Robert Gildea’s oral history of the year-long dispute is a much-needed bottom-up record that finally highlights the experiences of those most affected – the miners, their families and their communities.

The miners’ strike of 1984/85 was a Titanic battle between 184,000 miners and their communities on the one hand, and the mighty power of the state, most of the British media and the National Coal Board (NCB) on the other.

On the positive side, it helped to build new and lifelong friendships, developed social capital, raised some people’s organisational and speaking skills and changed their lives, while opening up opportunities for them and future generations.

On the positive side, it helped to build new and lifelong friendships, developed social capital, raised some people’s organisational and speaking skills and changed their lives, while opening up opportunities for them and future generations.

The mammoth money-raising tasks taken on by miners’ support groups to feed and clothe striking families required huge commitment and team work, as well as creative thinking, national and international co-operation and solidarity from the trade union and Labour movement.

There were also some fabulous concerts from musicians such as Billy Bragg, Lindisfarne and a host of others, which raised not only much-need funds but much-needed morale too, especially as the year-long dispute dragged on.

On the negative side, the strike split families and communities, and divided the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). The defeat and subsequent closure of the pits destroyed lives and livelihoods, and wrecked the social and economic fabric of mining communities, never to be restored.

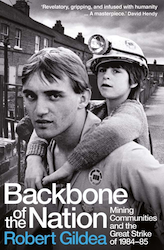

All this is portrayed in Robert Gildea’s welcome new book about those communities, Backbone of the Nation, published to mark the 40th anniversary of the start of the dispute in March this year.

It is a rich ‘bottom-up’ record that depicts the political and personal experiences of those involved at community level. While Gildea does mention the leading political figures, he primarily sets out to highlight the effect of the strike on the miners, their families and their communities, before, during and after 1984/85.

I was particularly drawn to Gildea’s title. It’s a term used by Thomas Watson, a safety officer from Fife, who was recalling his father’s description of the importance of miners and coal in earlier generation, a phrase that stands in marked contrast to Margaret Thatcher’s disgraceful depiction of strikers and activists as “the enemy within”.

As an activist myself in Durham throughout the strike, I opened this book hoping it would set the record straight by showing the fortitude and loyalty of striking families and their supporters, showcase their strength and organisational skills, and highlight their creativity and comradeship. I’m glad to say, I wasn’t disappointed.

Proud heritage

An emeritus professor of history at Oxford University, Gildea has given us the first oral history of the dispute, based on 148 two-hour interviews with miners, wives, children and activists recorded between 2020 and 2022 in selected coalfields across Scotland, Wales and England.

He spoke to people in the coalfields of Fife, Durham, Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and South Wales, focusing on a few communities in each area. He also spoke to some of the working miners, and refers throughout to the wealth of existing literature and research on the strike that’s appeared over the last 40 years.

He spoke to people in the coalfields of Fife, Durham, Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and South Wales, focusing on a few communities in each area. He also spoke to some of the working miners, and refers throughout to the wealth of existing literature and research on the strike that’s appeared over the last 40 years.

The book is divided into sections examining in turn the outbreak of the strike, the activities of support groups, Christmas 1984 and the return to work, and the afterlives of miners, wives and children. By comparing experiences across localities and regions, he adds greatly to our understanding of where, how and why they differed.

Far from being a dry record, this makes for great reading, prompting memories of forgotten details, people and events. The stories reveal how much support groups differed in their internal organisation and illustrates their varying relationships with NUM officials, as well as conflicts within the union.

I was particularly drawn to the women’s tales, the struggles they had with union officials and the interaction between supporters, feminists and miners’ wives – a problem in Barnsley, not so much in Durham or South Wales where most of the activists came from mining stock.

The author contacted his interviewees through various existing activist networks, community groups and mining heritage organisations. One of these was the North East Labour History Society, in which I’m involved, and he consulted interviews from our 2011 Popular Politics project deposited in the Durham County archive. Another is the Education 4 Action group formed in 2013 by activists from Durham’s 1984 support groups.

These people are proud of their heritage and eager to pass on to adults and children in Durham how miners and the union fought for fairer, stronger and more caring communities. They do so hoping to inspire people to fight for their communities today.

In fact, former mining areas up and down the country have tried with varying degrees of success to preserve their mining heritage. The biggest living demonstration of the legacy of the industry in the UK is the Durham Miners’ Gala, the annual mass trade union gathering that still draws thousands to the north east every July.

Big Meeting

The ‘Big Meeting’, as it’s known locally, was at serious risk of disappearing when the last pits closed in 1994, but has survived thanks to the fighting efforts of the Durham Miners’ Association.

The Gala’s continuing existence has undoubtedly helped revive interest in the county, as has the continuing success of the Durham Mining Museum, the Women’s Banner Group, and the Mining Art Gallery at Bishop Auckland, while on 2 March this year Durham City will host a national event to mark the 40th anniversary of Women Against Pit Closures. What’s more, we are looking forward to the re-opening of Durham Miners’ Hall at Redhills later this year after its multi-million pound renovation and redevelopment.

The Gala’s continuing existence has undoubtedly helped revive interest in the county, as has the continuing success of the Durham Mining Museum, the Women’s Banner Group, and the Mining Art Gallery at Bishop Auckland, while on 2 March this year Durham City will host a national event to mark the 40th anniversary of Women Against Pit Closures. What’s more, we are looking forward to the re-opening of Durham Miners’ Hall at Redhills later this year after its multi-million pound renovation and redevelopment.

In among his Durham stories, Gildea refers to the involvement of the “radical ginger group, the ILP”. He mentions Pat McIntyre’s singing and song writing, Vin McIntyre and Johnny Dent’s organising of food parcels, David Connolly’s badge selling, Neil Griffin’s music, and Lotte and Hugh Shankland’s banner making.

Indeed, members of Durham ILP were active in all aspects of the miners’ support group, rightly seeing it as the political battle of a generation, as did energetic and committed ILPers throughout the UK.

In Chester-le-Street, where I was based, the support group helped large numbers of travelling miners and their families. We met up on a regular basis in The Labour Club with David Connolly and through him got to know those hardworking Durham ILPers. They gave us a better grasp of what was happening politically, in particular given our disappointment with leading members of the Labour Party.

Soon after the strike ended David called most of the local activists together and we formed a new Chester-le-Street ILP branch. The 12 initial members included striking miners, miners’ wives and Labour activists, including Mary and Paul Stratford, and myself. Our stories are also in Gildea’s book, which – although not perfect in every detail – accurately portrays the excitement of the struggle, the pain of defeat and the long-term consequences. None of it is easily forgotten.

This depiction of mining communities mobilised to action by a hostile government, and the lasting impact on individuals, families and communities, is a wonderful record. It draws our attention to regional differences and the unfair treatment of striking miners at the hands of the state and NCB, treatment that left some jobless, some imprisoned and some victimised.

Ultimately, the defeat of the once mighty miners’ union was a watershed for the Labour and trade union movement. But it’s not just a matter of Labour history, for people in the communities featured by Gildea have endured poverty, drug and alcohol abuse in the years since, while some rely on food banks to this day. What’s more, there remain outstanding issues of justice yet to be resolved, not least those arising from events at ‘the battle of Orgreave’ in June 1984.

In his conclusion Gildea suggests that the miners’ strike, and the voices of those who sustained it for a year, offers some guidance and hope to public and private sector trade unionists in dispute today. The circumstances are very different, of course, but today’s activists could certainly draw courage and resolve from that momentous time.

—-

Kath Connolly is a member of Chester-le-Street ILP.

Backbone of the Nation: Mining Communities and the Great Strike of 1984-85 by Robert Gildea, is published by Yale University Press and available here in hardback for £25.

You can also pre-order the paperback, available from 12 March 2024 for £11.99.