The scale of Labour’s election defeat is hard to take in, says JONATHAN TIMBERS. But it has been a long time coming and will take a long time to put right.

This election defeat is not only a “disaster”, as John McDonnell correctly said, it is a body blow that might lead to the death of the Labour Party.

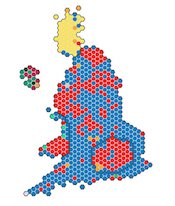

Labour is now the third party in Scotland after the Tories. It is no longer the biggest party in the west midlands or Yorkshire and the Humber, and it has lost a lot of ground in the north east. It has even fallen back significantly in Wales. It is miles behind the Tories in the south east and west, as well as the east of England and east midlands.

Labour is now the third party in Scotland after the Tories. It is no longer the biggest party in the west midlands or Yorkshire and the Humber, and it has lost a lot of ground in the north east. It has even fallen back significantly in Wales. It is miles behind the Tories in the south east and west, as well as the east of England and east midlands.

The only region in which it is predominant is London. Islington, at least, is safe, for now.

The scale of the disaster is hard to take in, but I think the result is actually worse than either 1983 or 1935. In 1983, it was obvious what went wrong. Many people were more aspirational and more individualistic than in the past, and Labour had to adapt to them to win power. The route back was obvious, even if taking it was painful and Labour eventually surrendered too much ground to achieve the 1997 landslide.

In 1935, the defeat came in the wake of the TGWU’s brutal coup against former pacifist ILPer George Lansbury’s leadership of the party, leaving a certain Major Attlee as ‘interim leader’. The dust had barely settled when the election took place.

The leadership, though on the right of the party by the standards of the time, took a much more aggressive stance towards the growth of fascism on the continent than either Lansbury or the Tory-led national government. It was ready to oppose appeasement and ‘speak for England’. The party was rewarded at the 1945 landslide after helping to deliver victory over the Nazis.

In contemplating the 2019 results as they came in on Friday 13 December, we have no such comforts. It truly was ‘Friday the 13th’ for the Labour Party, as relentless as any horror film. There is no obvious way out of this, as in 1983, because Labour’s constituencies are so profoundly split. Unlike 1935, we are not fighting the election immediately after a successful right wing leadership coup, confident that we can appeal to working class people in the future.

What should be obvious is that neither Corbynites nor Blairites, nor anyone in-between, can speak clearly and directly to the working class. One symbol for this has to be Laura Pidcock. She was a high-profile candidate who never stopped mentioning class and the workers, but found them abandoning her for Boris Johnson’s right wing populism. Another is arch-Blairite Mary Creagh who faced wipe-out in Wakefield. I can’t even begin to contemplate Dennis Skinner’s defeat or accept that it even happened.

Searching for reasons

Some people – notably Corbyn and McDonnell – have said the reason for the defeat was Labour’s inability to unite its supporters around their Brexit policy. There is some truth in this, but it is only a symptom of a much deeper problem.

Using the class definitions in the Great British Class Survey, Labour has four constituencies: the traditional working class, some parts of the technical middle class, new affluent workers and emergent service sector workers.

The latter three groups tend to be strongly remain and concentrated in cities. They are internationalist and socially liberal. They can be centrist or Corbynite, are trendy, successful and connected. Many are university educated.

In Blair’s day they might have been described as classless or middle class, but this is actually only true of some of them. Huge numbers are struggling to find security in employment and a home. They include the “networked individuals” that Paul Mason believes will help create a post-capitalist society.

The traditional working class tend to predominate in provincial towns in the north and midlands, once Labour’s heartlands, and also in many southern towns such as Reading, Luton, Harlow, Milton Keynes, Peterborough and the Medway towns. They have a strong sense of local identity and some believe Brexit is a rebellion against the billionaires and ‘liberal elite’ – the ‘citizens of nowhere’, as Theresa May memorably called them. They did not think that Corbyn was on their side.

We forget that some of those working class towns went Tory from 1979 onwards and have never been properly won back, except perhaps temporarily under Blair. There is no reason the north cannot go the same way.

To encourage this political migration, the Tories have promised substantial investment in health and education, stronger law and order and a defiant English nationalism. This platform reflected the interests and views of many traditional working class people. One can doubt whether the Tories will honour their pledges, with good reason, but if they become right wing populists they may very well retain the support of Labour’s heartland voters. You only have to look at the class basis of Erdogan’s support in Turkey or Putin’s in Russia to see that this is possible.

A long time coming

This crisis has been a long time coming. Its roots lie in 1979, when the southern working class peeled off from Labour to vote for insurgent Thatcherism. It deepened in the late 1990s after the election of Blair. During his first two years of government, the economy lost more well-paid working class jobs than under the previous seven years of Tory government. And the Labour government didn’t even shed a tear, let alone try to intervene in the economy in any meaningful way.

Instead, they made welfare, as they called it, increasingly contingent on demonstrating job market readiness. Working people, who had spent their lives saving and working to improve their children’s future, were treated like burdens. The best that many could hope for was a job in the warehouse in B&Q. People spent their life’s savings re-training.

Instead, they made welfare, as they called it, increasingly contingent on demonstrating job market readiness. Working people, who had spent their lives saving and working to improve their children’s future, were treated like burdens. The best that many could hope for was a job in the warehouse in B&Q. People spent their life’s savings re-training.

Globalism, we were told, could not be resisted. The only option was to become an entrepreneur of the self, to borrow a phrase from Hugo Radice’s useful article on neoliberalism. Blair singularly failed to do what he challenged Corbyn to do: to make the state “walk beside people rather than sit above them”. Rightly disgusted, many working class people turned away from Labour, for good.

Yes, these were difficult times for the left. Socialist economics, rather than the capitalist system, was in crisis. It would have been difficult for anyone to argue convincingly for massive state intervention in the economy. But the centre left did have some proposals, such as Will Hutton’s ideas about stakeholder capitalism, which could have taken society in a different direction.

But Labour didn’t do any of this when in office. Instead the Labour government just let the financial sector boom at the expense of the real economy. When the financial crisis came, there wasn’t much trust left for Labour, and in 2015 it seemed in danger of going the same way as other social democratic parties in Europe that had taken the neoliberal dollar.

Then Corbyn came along and broadened Labour’s policy horizons. I think this paragraph by Jack Shenker – from his article ‘Why Corbynism Matters’ in Prospect Magazine – describes his contribution much better than I can:

“The Corbyn project helped save Labour from ‘Pasok-ification’ – the fate of the traditional party of Greek social democracy… Who is to say how low such a Labour Party, stripped of anything but aspirational platitudes, may have fallen. By wriggling free of the ‘end of history’ ideological straitjacket that was fastened around formal politics after the Berlin Wall came down, Corbynism has expanded the politically possible; breaking up, as Lawson [chair of Compass] puts it, ‘the permafrosted soil that for 30 years had been too harsh for our dreams to grow in’.”

The 2017 election result seemed to reinforce this legacy. Then, of course, the manifesto was preceded by a high profile ‘Fiscal Credibility Rule’ and came with a small business manifesto. The miserable 2019 manifesto came with huge eye-watering spending commitments. Rescuing the policies from their wholescale rejection as a programme will require robust self-critical thought.

After such a comprehensive defeat it is difficult to respond politely to assertions that our manifesto was popular. Individual policies were popular, true, but their combination in an ill-disciplined and ever growing set of promises beggared belief.

The response from left-leaning people – whether economists or just people living in terraced housing – was much the same. They broadly supported it, but didn’t think it could be done. Even Jon Lansman, one of Corbyn’s closest allies, said as much: “I think maybe the manifesto was too long and too detailed, it’s a programme actually not for a government, but for 10 years.”

As Aditya Chakrabortty put it so well in The Guardian:

“What started as an anti-austerity movement is now a melange of ideas, most of which look and sound utterly absurd on a doorstep on a rainy morning.

“In the era of taking back control, Corbyn offered yet more direction from Westminster, with utilities run from the centre and hundreds of billions disbursed from remote state institutions. Many of these ideas are interesting, but few of them were properly worked through and none patiently argued for.

“Giving workers stakes in firms, a green new deal, free broadband: each one came well-intentioned but bedecked in question marks. Any radicalism that fails to ask the really thorny questions isn’t radical at all.”

Bright spots

There were bright spots in all this. I disagree with Chakrabortty about the Green New Deal. Rebecca Long-Bailey’s plans provided some of the more concrete and credible suggestions in the whole misbegotten document. Frankly, you could have run the election simply around her sections.

The level of specificity about what will be built and where, and how many jobs it could have created was impressive. The associated plans to revive the high street also might have gone down well in Dudley or Consett if anyone had heard them above the multi-billion pound noise promising giveaway this and giveaway that. We will never know for sure.

In general, though, I have to agree with Hutton, who said of the manifesto that “the party’s aim must also be to win, and to do so with a feasible policy framework”.

Labour also needed to show how the party intended to work with business. To revive the economy, Mariana Mazzucato pointed out, needs both public and private investment and a different narrative about business.

I believe this was as widely understood in Wrexham as in Oxford. It is not because of neoliberal hegemony that people think this way. It is because, to use a Gramscian term, they have ‘good sense’. Far from being the media-manipulated pawns of billionaires, they sometimes get it right.

Without setting out how business will boom in places like Brighouse or Blackpool, people won’t buy your story. Why should they? The two Eds made the same error back in 2015, with a similar result.

The fact that many of us thought the document was ‘formidable’ indicates that we are not on the same page as the people we need to convince. Or, for that matter, most educated left wing economic opinion.

“[Labour is] a party that grew out of social institutions,” Chakrabortty says. “[It needs] to turn itself into a social institution in precisely those areas it historically took for granted.” His suggestion is close to what the ILP has said in the past, but failed to say before or during this doomed campaign.

The left of all stripes and working class people need to reconnect. This is about listening to what people want and trying to help them get it, not about cold calling and offering them free broadband.

Once we have won back the trust that Blair, Brown, Miliband and Corbyn have lost, then people might start believing us again when we propose social and economic transformation.

Next time, if there is a next time, there needs to be a dialogue with our supporters and former supporters, before, during and after an election. And we need to listen and deliver in partnership with our supporters.

—-

16 January 2020

Ian, while Eric’s Labour In Crisis is a very important work for us all to return to, he would be the first to recognise that the Labour Party has experienced further difficulties since it was first published 37 years ago. Trade union membership is now only 55% of what it was then. Communities with a deep social bond in areas with industries such as coal mining, steel, cotton, printing and docks have now mainly disappered. Even railway workers are split up working for different companies. At one time many working class people were drawn together in their common work areas via pubs, clubs and even chapels.

Their common intererests turned most of them towards support for (and even involvement) with the Labour Party. Groups of Labour MPs came from such backgrounds themselves and could be indentified with and pressed. But now we have a new working class structure: people in short term employment; the gig economy; benefit systems which are complex and don’t properly deliver.

Then, since the Blairite transformation we have seen the emergance of many Labour MPs who the working class cannot identify with. For instance, Labour never engaged with them about the nature of the EU, nor sort to democratise it and get it to adopt relevant social welfare programmes. So they mainly voted to leave. Then Labour ignored their views and the reasons why these had arisen. We have also moved into a world of internet technology that many deprived working class people do not share. Labour In Crisis is certainly still an apt title for today.

Labour came up with a manifesto at the recent election which had many possibilities in it, if we ignore the confusing line it took on Brexit, starting from the key need to tackle climate change via ‘A Green Industrial Revolution’. We now require a parliamentary Labour Party that will take up the non-Brexit elements of the manifesto and propound and pursue these over time in ways that relate to the needs of our traditional avenues of support via deliverable forms of persistent gradualism. The immediate question is which leader and deputy (if any) will start the ball rolling.

I make some additional points on the manifesto on my website here.

10 January 2020

… now what I actually wanted to post was:

“… the success of Socialism will only follow a lengthy struggle to root Socialist ideas in the sectionalised trade union movement, the Labour party that gives expression to that movement, and the working class that identifies with that movement.” [Eric Preston, Labour In Crisis, ILP 1982]

At 59 I grow more and more conscious of how the values and mindset of Thatcherism have permeated our society. Children born in 1979 are now parents and almost grandparents themselves. They grew up largely with those values and have in many cases passed them on.

Preston’s statement rings truer than it ever did, and the struggle to root the ideas and principles of democratic socialism must – must – accompany the programme to win back votes.

Does the 2020 ILP agree?

10 January 2020

…..this is the Clive Lewis who has just picked a moment in our history when the country is at its most patriotic to talk about abolishing the monarchy (yes I know he didn’t quite but close enough). A more spectacular own goal it is hard to imagine…. I am all for challenging existing worldviews, but there are ways to do it, and times and places, and this is NOT it……,,

23 December 2019

Thank you, Barry for your kind remarks. I have mixed feelings about this article by Clive Lewis. It lacks focus and touches on lots of things without exploring them reflectively. How self critical will the membership be, if driven by social media? And what sort of relationship does he envisage between business and the state? But I agree we have to stop speaking in such abstract ways and start to relate to people so they can share our aspirations. All of us have a lot of thinking to do.

21 December 2019

Thank you Jon for sharing your thoughts in what is an impressive contribution. Lots to think about.

I must admit I was also impressed by this article by the MP Clive Lewis who is going to stand for the party leadership: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/19/im-standing-labour-leader-clive-lewis?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

Barry