Like many working-class socialists, Blackburn ILPer Johnnie Duxbury left only a faint footprint on the historical record. Yet his life of brave activism and everyday kindness ‘enriches our understanding of socialist commitment’, argues ROGER SMALLEY.

The whereabouts of the records of the Blackburn branch of the Independent Labour Party are unknown. Without them it is difficult to write a comprehensive history of that organisation, yet some account of its work, and the contribution Johnnie Duxbury made to it, is possible by using a variety of other sources.

Although some aspects of what follows are speculative, based on evidence that is still circumstantial, others can be corroborated from newspaper articles, artefacts and the oral tradition preserved by Johnnie’s family. A life recovered in this contingent way also throws light on the local fortunes of the ILP at a critical moment in its history, when the zenith of its influence was followed by its rapid collapse.

Although some aspects of what follows are speculative, based on evidence that is still circumstantial, others can be corroborated from newspaper articles, artefacts and the oral tradition preserved by Johnnie’s family. A life recovered in this contingent way also throws light on the local fortunes of the ILP at a critical moment in its history, when the zenith of its influence was followed by its rapid collapse.

Until the 1880s, the Liberal Party posed as the champions of the working class, and a handful of working men, mainly miners, sat in the House of Commons. They were known as Lib-Lab members because they spoke on behalf of their constituents on industrial matters, but otherwise took the Liberal whip.

By that decade, however, the brutality associated with unbridled capitalism was coming under closer scrutiny, and the demands for social reform led to the formation of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the Fabian Society in 1884.1 The SDF was Marxist and accepted that revolution was necessary to free the working class from oppression by rich and powerful elites. The Fabians preferred a gradual reform of society on more equitable lines through infiltration of local government and relentless pamphleteering.

The local Labour groups which were established in Scotland, Lancashire and Yorkshire in the early 1890s amalgamated into a national Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1893. Its aim was to win political power and exercise it on behalf of the working class through a programme of collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange. It also made specific demands for an eight-hour working day, improved facilities for the aged, sick and widowed, and an end to unemployment. Keir Hardie, founder of the Scottish ILP and MP for West Ham South, was elected its first chairman at its inaugural conference in Bradford.

Ambitions to introduce socialism on such a scale required mass support from the electorate, but the right to vote was not available to all men over 21 until 1918 and all women of that age until 1928. Many of those who could vote, including most trade unionists, still preferred to pursue their aspirations through the Liberal Party, so when the ILP fielded its first 28 parliamentary candidates in the general election of 1895 they were all defeated.

Efforts at closer co-operation with the SDF made little headway, but in 1900 a new body, the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), was created to improve electoral performance. Its secretary was James Ramsay MacDonald, a rising star within the ILP.

In 1900 its impact was minimal, as only two LRC-sponsored candidates were successful,2 but by 1906 a deal had been struck with the Liberal Party to limit mutual challenges in constituencies that could be won from the Conservatives. The tactic worked, for in that year’s general election the LRC won 29 seats, seven with ILP candidates, including Hardie, MacDonald and, in Blackburn, Philip Snowden.

The LRC changed its name to the Labour Party and for the first time a significant block of MPs sat in the independent interest of the working class. The ILP affiliated to the Labour Party immediately and expected to work with it on a common agenda. Dual membership was commonplace: for example, MacDonald, a member of the ILP since 1894, became the leader of the Labour Party in 1922, and 120 of the 191 Labour MPs elected in 1924 were also ILPers.

The link lasted until 1932, but it was characterised by frequent tensions. The most serious of these concerned trade union support, which overwhelmingly preferred the Labour Party’s more moderate line; involvement in the 1914-18 war, which Labour supported and the ILP opposed; and unemployment legislation, the Labour Party’s record on which was heavily criticised by the ILP.

Choosing the ILP

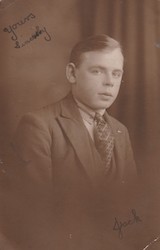

It was during these years that Johnnie became an ILP activist. He was born in Blackburn in 1907 and became an apprentice shuttlemaker in 1921 after leaving school at 14. His father, Albert Duxbury, was a prominent member of the Shuttlemakers’ Union and its president from 1936 to 1946.

Such a close association with the union’s efforts to limit capitalist exploitation of its members must have influenced Johnnie’s decision to become politically active. He joined the Blackburn branch of the ILP rather than its Labour equivalent because of Labour’s participation in the wartime coalition government led by Lloyd George. This alliance had won the 1918 election by a large majority and deprived Snowden, the ILP’s anti-war incumbent, of his Blackburn seat in the process.

Such a close association with the union’s efforts to limit capitalist exploitation of its members must have influenced Johnnie’s decision to become politically active. He joined the Blackburn branch of the ILP rather than its Labour equivalent because of Labour’s participation in the wartime coalition government led by Lloyd George. This alliance had won the 1918 election by a large majority and deprived Snowden, the ILP’s anti-war incumbent, of his Blackburn seat in the process.

Albert had responded to Kitchener’s call for volunteers in 1914 but, like so many, became disillusioned with how the government and the army handled the conflict. For him the ordinary soldiers were ‘lions led by donkeys’ and, as a prisoner of war, he felt only gratitude for the considerate treatment he received from his German captors.3

These experiences made Johnnie a pacifist and a probable participant in the annual No More War rallies held in Blackburn in the 1920s. On these occasions the Marxist claim that capitalists used war to set worker against worker for their own gain was often heard. It was an interpretation that Johnnie accepted and upon which he subsequently built a wider political philosophy.

The failure of the coalition and its Conservative successors to provide better housing and more jobs for the working class allowed Labour to make spectacular gains in the general elections of 1922 and 1923. The first Labour government took office in 1924 with MacDonald as Prime Minister, and 45 ILP-sponsored MPs in the House of Commons alongside 146 from the Labour Party.4

It was a short-lived minority administration and Johnnie was not impressed by its record. No disarmament policy was implemented and unemployment was not tackled effectively. Indeed, it was the view of The Clear Light, a journal published by Blackburn ILPers Ethel and Alfred Carnie Holdsworth, that home secretary Arthur Henderson’s proposed factory legislation showed Labour had no stomach for socialism. It offered only minor adjustments to working practices, the paper claimed, and was simply a ruse to avoid immediate industrial confrontation rather than an honest attempt to hobble capitalism.5

The ILP’s response was to form the Guild of Youth. It had 171 branches by the end of 1925, including one in Blackburn. Johnnie was 18 and most likely joined the Guild, for a photograph exists of him at about that age wearing a lapel badge that his daughter believes to be a token of the organisation. If the assumption is correct, Johnnie’s political views will likely have matched those in the ILP’s policy statement, Socialism In Our Time.

It was issued in 1926 and emphasised the differences between the ILP and the Labour Party, expressing impatience with Labour’s policy of gradual reform within the capitalist system. Instead, it proposed to achieve socialism immediately through the introduction of a national living wage to ensure adequate food, clothing and housing for all, and nationalisation of banks, railways, mines, utilities and land. Socialism In Our Time also recommended credit controls to stabilise prices and prevent deflation, and pledged ILP support for trade unions and the Parliamentary Labour Party so these changes could become a reality.6

It was designed to appeal to young, keen socialists like Johnnie but was rejected by the Labour Party leadership. MacDonald and Snowden both believed it would prevent pragmatic responses to Conservative and Liberal policies, and Snowden, one of the founding fathers of the ILP, felt so deeply that he resigned from the organisation. The Trade Union Congress (TUC) was critical too, saying it would impose restrictions that undermined its negotiating position with employers.

That was also the year of the General Strike. The TUC called it off after nine days without winning any concessions from the government, a surrender the miners refused to accept. They stayed out for a further six months and were backed by the ILP.

AJ Cook, general secretary of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, and James Maxton, the new ILP chairman, issued a joint manifesto urging the Labour Party to move from gradualism to a more radical position, and thus counter the challenge of the Communist Party (CPGB) which had been formed at the beginning of the decade.

The manifesto had little effect, although in Lancashire it led ILP members to condemn the Labour Party as “compromisers whose only object was office”,7 and declare their own “unceasing war against poverty and working-class servitude”8. The missing minutes would establish the precise response of the Blackburn branch, but in their absence there is no reason to think that Johnnie would have disagreed with these sentiments.

The deepening rift

Socialism In Our Time and the Cook-Maxton manifesto deepened the rift within the political left, and the ILP was the main casualty. It lost much of its moderate members to the Labour Party and its revolutionary wing to the CPGB, so that its 1,075 branches in 1926 were reduced to 746 by 1929.9

Nevertheless, the ILP sponsored 58 candidates in the 1929 general election, 37 of whom were elected, and Labour was able to form its second government with MacDonald again Prime Minister.

It was the first time all adults over 21 were able to vote and the 22-year-old Johnnie cast his ballot for Mary Hamilton, Labour’s candidate in the Blackburn constituency. She won, but her party’s reluctance to promote socialist measures mortified the ILP. Indeed, when Snowden used the slump in trade that followed the Wall Street Crash as an excuse for omitting nationalisation from his 1930 budget, Johnnie may well have supported the alternative submitted by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

It was the first time all adults over 21 were able to vote and the 22-year-old Johnnie cast his ballot for Mary Hamilton, Labour’s candidate in the Blackburn constituency. She won, but her party’s reluctance to promote socialist measures mortified the ILP. Indeed, when Snowden used the slump in trade that followed the Wall Street Crash as an excuse for omitting nationalisation from his 1930 budget, Johnnie may well have supported the alternative submitted by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

That was Oswald Mosley who proposed to create jobs by nationalising industry, introducing a liberal credit scheme and increasing pensions to encourage early retirement. The Cabinet rejected Mosley’s plan leading him to resign from both the government and the ILP. Within two years he had formed the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Snowden’s fiscal timidity caused much dissent within the Labour Party and among its supporters, for few could accept his intention to cut unemployment benefits, reduce public sector wages and introduce a means test. Consequently, the government collapsed in 1931. Its replacement was a Conservative-dominated coalition supported by a Liberal and Labour rump, although MacDonald stayed on as Prime Minister and Snowden as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Any remaining sympathy within the ILP for further co-operation with Labour was destroyed by the apostasy of MacDonald and those who joined him in the National Government. The ensuing election compounded the left’s disarray, for the Labour Party was reduced to 46 MPs and the ILP to five.10 The ILP determined to have nothing more to do with political gradualism and disaffiliated from Labour in 1932.11

The ILP hoped it could offer a clearer message about socialism and thus increase its appeal. To that end, a recruitment drive was launched during which Maxton visited Clarion House at Roughlee on several occasions. As a keen cyclist and regular attender, it is highly likely that Johnnie met Maxton there and perhaps they shared their enthusiasm for Esperanto, the key, both believed, to promoting international working-class unity.12

But the ILP’s expected expansion did not occur. Disaffiliation isolated it from the mainstream of working class support, so by 1935 membership had fallen to below 5,000 and only 284 branches remained active, many of them with no more than nominal support.13 Blackburn was one of them, although apart from Johnnie, Manky Cohen and Bob Parker, no other diehards have yet been identified. Together this trio faced the fascist challenge of 1934.

Before then BUF activities had mainly been confined to the London area where contingents from the ILP and other radical groups in the north west travelled to protest against them.14 It is not known if any of the Blackburn branch took part, but in the absence of Labour Party intervention it was they who led the anti-fascist effort in Blackburn when Mosley began to recruit in Lancashire in 1934.

Mosley tried to exploit working class disaffection with traditional political parties during a time of depression in the cotton industry and was able to establish BUF branches in several of the weaving towns, including Accrington, Nelson and Blackburn.15 Mosley’s tactic was to argue at mass rallies that his policy of protecting Lancashire from Indian competition would save thousands of jobs.16

Three meetings were held in Blackburn. That on 6 January 1935, held in King George’s Hall, was disrupted by Johnnie and his group. They heckled the speakers, interrupting them with pre-prepared questions, and fought running battles with BUF stewards.17 A similar demonstration at Bury 10 days later may also have involved the Blackburn anti-fascists.18

Press coverage of these events does not indicate just how well organised and executed the ILP campaign was, for no mention is made of the antisemitic graffiti they erased, nor of their distribution of anti-Mosley propaganda around Blackburn market on BUF meeting days. Johnnie co-opted his cousin Joan to help with the leafleting and carefully planned their escape routes in case the Blackshirts found out what they were doing.19

It was a brave effort by a handful of young socialists against far more numerous opponents known for their violence towards those who tried to obstruct them. And it was successful: the fascists’ disrupted speeches made little impact and they abandoned their programme before the end of the year.

The ILP’s decline

After the second world war Johnnie joined the Communist Party. His reasons for doing so are not known, but the factors that influenced his decision are. The ILP and the CPGB were the only political organisations to give support to the Spanish government in its fight against Franco’s fascist coup in 1936. Johnnie applauded the ILP’s backing of the anarchist militias and the social revolution they effected in Catalonia. Indeed, he would probably have gone to Spain himself had his mother not been seriously ill.20

He lamented the rift between the anarchists and communists, which proved disastrous for the Republican cause, and was dismayed by the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939. That ended in 1941, however, and the USSR’s crucial role in the defeat of Hitler caused an increase in CPGB membership just as the ILP went into decline. At the general election of 1945 only three ILP candidates were successful, and they joined the governing Labour Party after the death of James Maxton in 1946.

He lamented the rift between the anarchists and communists, which proved disastrous for the Republican cause, and was dismayed by the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939. That ended in 1941, however, and the USSR’s crucial role in the defeat of Hitler caused an increase in CPGB membership just as the ILP went into decline. At the general election of 1945 only three ILP candidates were successful, and they joined the governing Labour Party after the death of James Maxton in 1946.

Deprived of the party he had supported for 20 years Johnnie felt that the CPGB was now the only political home available to him, and he became comfortable there. His daughter recalls that the Daily Worker was her father’s newspaper and, as a primary school pupil in the early 1950s, she was proud to tell her classmates “my dad’s a communist”.21

In 1959 a meeting of the Blackburn branch of the CPGB was disrupted by supporters of Mosley, who was attempting to revive his political career by standing on a racist platform in that year’s general election.22 It was 25 years on from the King George’s Hall demonstration, but Johnnie again found himself arguing with fascists.23

By then he was 52, and evidence, even circumstantial, of his later political activism has yet to be found. But committed socialists seldom abandon their beliefs, and Johnnie maintained his concern for the oppressed and his conviction that socialism was the hope of the world until his dying day.24

Like his father, Johnnie believed that regular voting was a sacred duty owed to those who had struggled to win that right for the working class. His disagreements with the Party notwithstanding, he always voted Labour because there was no acceptable alternative, but he got greater satisfaction from practicing his principles day-by-day in the tradition of the ILP’s ethical socialism.

Examples of the help he gave to the afflicted and those less able to stand up for themselves are numerous, and well attested in the memories of his family and friends. The prejudices of the times denied him the opportunities his intelligence merited, but he encouraged others to get on.

He taught himself how to use a micrometer, for instance, so that he could pass on that skill to an unemployed friend, Dick Ashworth, and this enabled him to get work. A neighbour, Jim Gillibrand, became a pharmacist because Johnnie helped him to complete the necessary university and grant application forms and found him a quiet place to study in his own home. Many other acts of kindness and generosity were made anonymously.25

Some of those around him received public recognition. His father Albert was awarded the British Empire Medal in 1952 for a lifetime of service to his trade and his union. And his friend, Benny Rothman, was celebrated for his role the Kinder Scout trespass and anti-fascist activities in the 1930s.

Johnnie was involved in all of these, but few knew it. His instinct was to avoid the limelight, so he did not reveal the part he had played in the trespass, for example, until just before he died, 60 years later.

Despite his reticence, sufficient evidence has survived to show how significant Johnnie’s role in local politics was, and this is important because working-class socialists have left only a faint footprint on the historical record. His activism is therefore representative of all those who worked for socialism but of whom we know nothing, and it enriches our understanding of the nature of socialist commitment amongst his class.

But it is also personal, for it was carried out with a degree of dignity and decency that many could not have matched. Rothman understood the value of his friend’s anonymous contribution, and because of it he called Johnnie “a wonderful comrade”.26 It is a fitting tribute.

—-

Roger Smalley is a local historian and author of Breaking the Bonds of Capitalism: the political vision of a Lancashire mill girl, a biography of Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, another Blackburn ILPer who became a poet, novelist and journalist but died in obscurity.

Roger regards this article as ‘a work in progress’ and is hoping to find out more about Johnnie Duxbury’s life and the activities of Blackburn ILP. He would love to hear from anyone who has access to relevant sources of information, especially the Blackburn ILP minutes.

Please contact Roger via: barbsandmike@gmail.com or drop a note in the Comment box below if you think you can help.

Read a moving tribute to Johnnie by his daughter, Barbara Hargreaves, here.

Notes and References

- For example, Thomas Carlyle indicted capitalism in Past and Present (1843) and Henry George blamed social inequality on laissez-faire economics in Progress and Poverty (1881). Both were influential texts on early socialist organisations.

- Keir Hardie (Merthyr) and Richard Bell (Derby).

- Barbara Hargreaves, oral testimony, January 2021. Cf the experience of Alfred Holdsworth in R. Smalley, Breaking the Bonds of Capitalism (Lancaster University, Lancaster, 2014) p. 67.

- The First Labour government was dependent on the support of 159 Liberal MPs. The Conservatives won 258 seats.

- The Clear Light, March 1914. Arthur Henderson was Home Secretary and MP for Burnley.

- Dowse, Left In The Centre (Longmans, London, 1966) pp 212 – 215.

- Northern Voice, 6 July 1918. The CPGB was formed in 1920.

- Dowse, op.cit., 216.

- Ibid., p.150.

- Bellamy and J. Saville (eds), Dictionary of Labour Biography. Vol. 1. (Macmillan, London, 1972) p.226.

- Hodgson, Fighting Fascism (MUP, Manchester, 2010) p.112.

- Barbara Hargreaves, cit., W. Knox, James Maxton (MUP, Manchester, 1987) p.109.

- Dowse, op.cit. p 193.

- Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2000) p.34.

- Northern Daily Telegraph, 23 July 1934. The Accrington BUF office was in Jacob Street. The Nelson BUF had more than 100 members by February 1935. See J. Liddington, The Life and Times of a Respectable Rebel (Virago, London, 1984) p.419.

- Northern Daily Telegraph, 23 July 1934.

- Lancashire Evening Post, 7 January 1935. The other BUF meetings in Blackburn were on 9th March 1935 and 20th October 1935.

- Northern Daily Telegraph, 16 January 1935.

- Barbara Hargreaves, cit.

- Barbara Hargreaves, cit.

- Barbara Hargreaves, cit.

- Copsey, op.cit., pp 103 – 104. Mosley polled 8.5% of the vote in North Kensington.

- Roger Smalley, oral testimony, January 2021.

- Barbara Hargreaves, cit.

- Ibid.

- Personal correspondence between Benny Rothman and Barbara Hargreaves.

16 March 2021

Such an interesting article, brilliant analysis. Thanks for sharing.