BEN SALTONSTALL reviews a powerful and timely study of the influence of identity politics on recent British history. It’s an analysis the left must consider if Labour is ever to rise from the ashes of 2019.

Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics by Maria Sobolewska and Robert Ford charts the course of events that has placed the conflict between ethnocentric voters and a growing, highly educated, ethnically diverse electorate centre stage in British politics.

It’s a process that culminated in the Brexit referendum and subsequent general elections, when voters were increasingly divided by culture rather than economic factors.

It’s a process that culminated in the Brexit referendum and subsequent general elections, when voters were increasingly divided by culture rather than economic factors.

The book draws on extensive and accessible use of robust evidence from academic research to argue that this state of affairs arose from a conflict between ethnocentric “identity conservatives” and “identity liberals”.

Essentially, ethnocentrism is a “them versus us” mentality that usually finds expression around national identity. Ethnocentric voters feel under threat and ignored, the authors argue, largely because political elites have indeed ignored them over several decades, with disastrous results.

Ethnocentrism has been a force in British politics throughout the post-war period, and the authors suggest it may even be a feature of human nature. How important it is politically depends on the circumstances of the time – “demography is [not] destiny”, they stress.

Notwithstanding Brexit, and the huge Tory majority won on the back of the slogan ‘Get Brexit done’, ethnographic voters are a declining demographic, while there are more and more identity liberal voters.

This is explained by two trends: the increasing proportion of ethnic minorities in Britain, and the increasing proportion of the population who have a university education.

The first group are liberal through necessity, they say, although many share the attitudes of identity conservatives. These “necessity liberals” generally support progressive views due to their own communities’ experiences of discrimination. The second group are “conviction liberals”. Their education has made them value openness and anti-racism above all else. Over time, the two groups are likely to form more than half the electorate.

What’s more, the authors claim, identity conservatives are much more liberal now than in the past. Attitudes on issues such as gay and lesbian rights have fundamentally shifted over the last 30 years and identity conservatives share the antipathy of identity liberals to racism, although they may define the boundaries differently, especially when it comes to immigration and cultural diversity.

Identity conservatives usually oppose racial discrimination and harassment, and younger identity conservatives are strongly anti-racist. In fact, it is this “anti-racist norm” that is the source, the authors argue, of some of the polarisation of recent years.

Identity conservatives feel as if the goal posts have shifted over the years; that they are unfairly characterised by identity liberals – a not unreasonable response to social developments, the authors suggest. Potentially, this means identity liberals are partly responsible for deepening cultural divisions and inflaming the political tensions related to them – although the authors don’t explicitly express this highly controversial view.

A political explosion

There are two related processes that can turn social and cultural attitudes, such as identity conservatism, into a political force. The first is activation when concerns among sections of the electorate come to the fore. The second is mobilisation when these concerns are harnessed by politicians.

These processes are essential components of the recent politicisation of cultural identity. Indeed, recent governments have managed both to activate and mobilise identity conservatives, sometimes unwittingly or with unintended results. As the writers put it: “It is not a simple or inevitable process for any latent social conflict to become mobilised.”

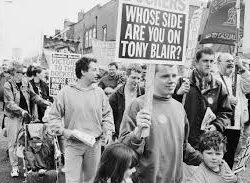

New Labour comes in for especially harsh treatment. Its movement to the political centre, and its convergence with free market thinking, took away the political choice from left-leaning identity conservatives who were not comfortable with the right’s economic ideas. Its promotion of identikit politicians who had moved from university to policy unit to parliament, and had little contact with ordinary voters, increased the distance between Labour and its former identity conservative voters.

New Labour comes in for especially harsh treatment. Its movement to the political centre, and its convergence with free market thinking, took away the political choice from left-leaning identity conservatives who were not comfortable with the right’s economic ideas. Its promotion of identikit politicians who had moved from university to policy unit to parliament, and had little contact with ordinary voters, increased the distance between Labour and its former identity conservative voters.

Moreover, New Labour’s style of campaigning – relying on ‘voter contact’ with electors who had previously supported Labour – also contributed to this long and painful divorce from its electoral base. An increasing number of voters never experienced a one-to-one connection with the party.

This lack of personal contact contributed to on-going estrangement, visible in the decline in voter turnout. “The largest turnout declines of all [were] found among younger identity conservatives”, those who had never voted before and had no existing relationship with party politics.

In addition, immigration from central and eastern European Union countries increased hugely during the New Labour period, activating identity conservative concerns. Areas that had never experienced high levels of migration were suddenly exposed to large numbers of migrants. The liberal left dismissed these concerns as racist or just ignored them. As a result, they left the ground open for others to influence the political discourse.

This was summed up at the 2010 general election when Gordon Brown described Gillian Duffy, a long-time Labour voter in Rochdale, as “that racist woman” when she raised concerns about immigration.

The Cameron government only made things worse, not through austerity but by setting unnecessary and unachievable public immigration targets, which highlighted the issue of immigration while demonstrating that EU membership prevented the government from meeting them. This set up the political stage perfectly for Nigel Farage and the Brexit referendum.

Meanwhile, Labour’s attempts under Ed Miliband to win back identity conservative voters by showing concern about immigration did not wash with that constituency while simultaneously outraging identity liberals. In 2015, old attachments to Labour still had some influence on election outcomes, however, and older identity conservative voters voted Labour in sufficient numbers to hang on to ‘red wall’ seats.

That all changed after the 2016 Brexit vote, which let the genie out of the bottle and fully mobilised identity conservative feeling. Labour’s support quickly divided – identity conservatives left the party while identity liberals moved towards it.

Brexit Blairism

By then Labour was led by Jeremy Corbyn and Corbynism was on the rise. The authors’ describe it as “Brexit Blairism”.

Blair’s strategy, of course, was to move economic policy closer to the Tories but still retain enough that was socially democratic to hang on to economically left-wing voters who desperately wanted to keep the Tories out. Labour’s 2017 manifesto similarly shadowed the Tory position by promising to leave the EU while offering remainers “tariff-free access to the single market” and putting Customs Union membership “on the table”.

Blair’s strategy, of course, was to move economic policy closer to the Tories but still retain enough that was socially democratic to hang on to economically left-wing voters who desperately wanted to keep the Tories out. Labour’s 2017 manifesto similarly shadowed the Tory position by promising to leave the EU while offering remainers “tariff-free access to the single market” and putting Customs Union membership “on the table”.

Corbyn calculated that identity liberal voters would feel they had nowhere else to go and vote Labour anyway. The strategy seemed to work in 2017, but that election result “flattered to deceive”, say the authors, “masking the hollowing out of support in formerly rock-solid leave-voting seats with large concentrations of identity conservatives”.

They have a point. Despite Theresa May’s hapless election campaign, many safe Labour seats became marginal and some were lost, such as ILPer Harry Barnes’s former seat in North East Derbyshire. Yet, as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation reported, Labour also attracted many low income voters with its strong commitment to social justice and redistribution of wealth and power.

I believe the authors miss an opportunity here to apply their own framework creatively in understanding the 2017 result. Labour gained identity liberal votes – including many from people who had not voted Labour before – with its promise to abolish tuition fees and introduce explicitly radical tax and spend policies. It attracted many students and graduates, as the victory in Canterbury and other seats with large higher education institutions showed. The absence of consideration of these factors is a glaring omission in the Brexitland account.

By 2019, however, the landscape had changed. Dislike of Corbyn and fragmentation of the remain vote led to Labour’s debacle. On this occasion, Corbyn’s Brexit Blairism put off both remain and leave voters.

Again, the authors say nothing here about Labour’s economic agenda, which had played such a crucial role in the 2017 result. With its Brexit-bridging position floundering, I believe Labour overplayed its economic policies in the hope it would attract voters from both sides of the Brexit divide. Instead, it widened Labour’s credibility gap, turning a likely defeat into a rout.

The authors provide a more satisfying account of politics in Scotland where – following their ‘demography is not destiny’ theme – ethnocentrism has been used to bring progressives to power. There, they say, a left-leaning social democratic party has achieved political dominance by developing a narrative that bridges the divide between identity conservative and identity liberal voters.

The SNP has argued that Tory England is preventing Scotland, with its inherent values of openness and solidarity, from achieving a fairer society where everyone will be better off. This appeals to identity conservatives’ ‘them and us’ view of the world, while there is even evidence that some have become more left wing in their economic views because of this nationalist approach. It also appeals to identity liberals who support the SNP’s anti-racism and left-leaning policies.

While this might not be encouraging to socialists who would like to win support without appealing to nationalist sentiments, it does seem to be a fair summary. Drawing lessons from this for England, however, is not particularly easy. Perhaps Labour could do more to create a ‘them versus us’ narrative about super-rich oligarchs and finance capital, inflating assets and suppressing the real economy?

There are huge challenges for the right too, they say. The Conservative Party has thoroughly alienated its identity liberal voters while many of its seats in the south east are becoming more ethnically diverse. In the future, voters there are likely to feel less attuned to a Tory party trying to appeal to narrow nationalist sentiments.

Meanwhile, its new red wall voters are hardly Conservative converts. If the Tories do not deliver what they want, they may well swing to populist parties that better appeal to their ethnocentric views. By this analysis, the Conservatives face an existential crisis just as deep as Labour’s.

Three futures

While they don’t claim to have a crystal ball, the authors suggest three potential political futures that could arise from all this.

The first is that Conservative policies are successful and immigration declines, allowing a return of the two-party left-right split between a Labour party that believes the state should have a bigger role and capitalism is inherently flawed, and a Conservative party that wants to allow business to keep making money and opportunities without counter-productive state intervention.

The second is that Labour becomes a party of the wealthy suburbs and cities, where identity liberals congregate. According to Sobolewska and Ford, whoever mobilises identity liberals could dominate the next decade. Labour could become more centrist again to win their votes.

The third possibility is that both Labour and Tory parties fail to accommodate identity conservative and liberals, and both die. There are lots of reasons why this may not happen, but it is not impossible.

Brexitland provides a compelling account of recent political developments, but the authors themselves admit its limitations. There needs to be further research, they say, about the interactions between “new identity conflicts and old economic conflicts”.

They also reject the term ‘working class’ as useless, saying, “the moniker of working class [used] to describe identity conservatives … is a distraction, which is misleading in its foregrounding of economic factors”. They do not ask themselves if new class formations, such as those described by Mike Savage and the Great British Class survey, might be helpful.

Many identity liberal voters are trapped in rented accommodation and the gig economy. They may have the sort of social and cultural capital that identity conservatives envy, but they are often much poorer in terms of economic capital. There is some evidence that it is these economic factors that have activated many of them.

On the whole, Brexitland includes a lot for the left to chew on, even if it also contains a few fish bones. It raises the important question of how we re-connect with identity conservatives who are left-leaning in their economic values, and provides an account of recent political history that the left must consider if Labour is ever to rise from the ashes of 2019.

Falling back into identity liberal comfort zones – fixating on Keir Starmer’s affection for the union jack, for example – is not the way to do it. Merely sitting in front of a union jack won’t do much good either without substantial changes in the way Labour engages with economically left-leaning identity conservatives.

—-

Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics, by Maria Sobolewska and Robert Ford, is published by Cambridge University Press and costs £15.99.

See also: ‘Labour should withhold support for Johnson’s Brexit deal’.