The ILP was a major force behind opposition to the First World War in many parts of the country. The south London borough of Southwark was no different, as new research by JOHN TAYLOR has revealed.

Southwark opposition to the war of 1914-’18 had two poles. One was in Bermondsey in the north of the borough, based around the Quaker socialists, Alfred and Ada Salter, whose double centenary as elected Labour representatives is being celebrated this year.

The Salters were both active at national level. Alfred sat on the national committee of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), which sprang into action when conscription came in, and became its chairman in 1918. Ada was in charge of the Fellowship’s maintenance committee, which provided financial support for the relatives of imprisoned objectors. The NCF grew quickly – by May 1916 there were 165 branches across the country, including 31 in London.

The Salters were both active at national level. Alfred sat on the national committee of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), which sprang into action when conscription came in, and became its chairman in 1918. Ada was in charge of the Fellowship’s maintenance committee, which provided financial support for the relatives of imprisoned objectors. The NCF grew quickly – by May 1916 there were 165 branches across the country, including 31 in London.

The Salters are well known, of course, not only by local reputation but thanks to biographies of Alfred by Fenner Brockway, and of Ada by Graham Taylor. There are statues of them by the River Thames, while a road and school is named after Alfred.

Alfred’s secretary, Archie Lewis, was also secretary of the Bermondsey NCF, which according to Brockway’s biography, was formed within the local branch of the ILP and included men who attended the Adult School started by Alfred at Bermondsey Settlement. Its base, the Labour Institute in Fort Road, was destroyed by a German bomb in 1940.

The second and rather more surprising centre of resistance was in Dulwich, in the south of the borough, an area hardly known at all for anti-war activity. Here too it was the ILP that generated opposition.

Until his arrest, the leading figure was Arthur Creech Jones, a bookish civil service clerk, aged 25 in 1916. He lived in Peckham and was secretary of Camberwell Trades and Labour Council (Dulwich and Peckham were then part of the borough of Camberwell).

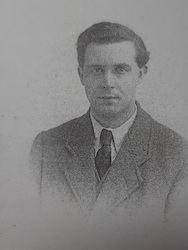

Creech Jones (pictured left in 1916) is a largely forgotten name now, but the prison correspondence between him and his lively cousin, Violet Tidman, runs like a thread through this narrative. They married after the war and he went on to become a Labour MP, serving as colonial secretary in Attlee’s government.

Creech Jones (pictured left in 1916) is a largely forgotten name now, but the prison correspondence between him and his lively cousin, Violet Tidman, runs like a thread through this narrative. They married after the war and he went on to become a Labour MP, serving as colonial secretary in Attlee’s government.

Jones was an absolutist – one of the 1500-plus men who, unlike the majority of conscientious objectors, chose to stay in prison on anti-war principle rather than accept alternative service or transfer to a labour camp under what was known as the Home Office scheme. Arrested in September 1916, he served four terms of hard labour and only stepped free in April 1919.

The correspondence (housed in the Bodleian Library) contain some vivid material, including a powerful four-page letter written from the guardhouse at Hounslow barracks while Jones was awaiting court martial. In it he describes to his former comrades on the trades council the company he now found himself in, of wounded men and men released from military custody.

“You begin to understand after talking to these men what war and militarism mean. In many cases bitterness has eaten into their souls. You faintly comprehend the tragedy of war and of army life. Cruelty and inhumanity you hear about which make your heart ache. The men are mere numbers, just so much lumber and no better than dogs in the eyes of the authorities. From the men who have seen the horror and the tragedy of the battlefield you get the greatest response to our ideals. They tell you frankly they appreciate and admire the stand we conscientious objectors are making…

“Every soldier you meet will express his utter detestation of the army and his desire for peace. Apart from the ‘constitutional’ objections to granting votes to the soldiers, the politicians know that the soldiers realise the ghastliness, costliness and folly of the war and they know that the soldiers would vote for peace tomorrow. If you listen to the soldiers at work you will frequently hear them humming the ‘Red Flag’. Every evening in the twilight (for we have no artificial light) we sing our labour songs out into the night.”

Jones’s statement to his first court martial is also carefully preserved:

“I view war merely as a test of might, resulting from dynastic ambitions, commercial rivalries, financial intrigues and imperialistic jealousies. It is a stupid, costly and obsolete method of attempting to settle the differences of diplomatists, in which the common people always pay with their blood, vitality and wealth.”

Though expressed with feeling, Jones’s letters from prison are high-minded, slightly formal and perhaps a little dull. Those from his cousin Violet, a 23-year-old school teacher, are altogether livelier.

In one of the first she gives an eye-witness account of the ‘Great Russian Meeting’ held in Albert Hall in 1917 to welcome the February revolution and demand a similar Charter of Freedom for Britain. There wasn’t an empty seat to be had: 12,000 people with tickets crammed in; 5,000 others turned away:

“I have never been to anything half so inspiring. We were very fortunate in having about the best-situated box in the place. Israel Zangwill and all the chief pacifist trade unionists spoke and Clara Butt sang, ‘Give to us Peace in our Time, O Lord’. Everyone said what he thought he would and what he had been dying to say for the past 2½ years. They demanded an amnesty for all political prisoners and mentioned with reverence, amid peals and peals of cheers, you men in prison. It was certainly a great triumph.”

Local resistance

Violet’s chatty letters also give regular glimpses of anti-war activity, both in Camberwell and further afield. In November 1917 she wrote excitedly:

“On the Sunday… you’d never guess – I tub thumped on P’ham Rye!! Honour Bright! on the subject nearest my heart. Chaired for Mrs Bouvier & yarned for ¼ hr at least & got a big crowd. It’s surprising how sympathetic people are now. As I told them. I needed no pluck as the Ch. of England had now taken up your cause. I alone sold 4/- worth of Dreadnoughts [Sylvia Pankhurst’s paper]. Flo’ and Rose got 1½ doz signatures.”

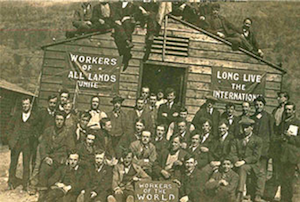

The Dulwich NCF branch (pictured left) covered the whole of Camberwell borough and had members in Lewisham and Deptford as well. It met in East Dulwich, an area very different to the lawned and leafy idyll around Dulwich College and the Picture Gallery. Found on the other side of Dulwich Park, this is a wedge of quite modest terraced houses, now widely gentrified but built in the late 19th century for working-class occupation, in some cases (initially at least) two families to a dwelling.

The Dulwich NCF branch (pictured left) covered the whole of Camberwell borough and had members in Lewisham and Deptford as well. It met in East Dulwich, an area very different to the lawned and leafy idyll around Dulwich College and the Picture Gallery. Found on the other side of Dulwich Park, this is a wedge of quite modest terraced houses, now widely gentrified but built in the late 19th century for working-class occupation, in some cases (initially at least) two families to a dwelling.

Here, hidden away, was Hansler Hall, the headquarters of Dulwich ILP of which Creech Jones was also secretary. It was the base for a full programme of political and social activity and the NCF branch met there on Wednesday evenings, when some 25 people listened to missives from head office, heard the imprisoned men’s letters, and gave friendship and support to their families.

One of those attending was branch secretary Sarah Cahill, the wife (or perhaps widow) of a railway signalman and mother of four children, whose only son, William, was a conscientious objector.

Cahill and others made jail visits and reported back to head office. They also lobbied MPs and in July 1917 the branch produced a smart buff-coloured booklet entitled What are Conscientious Objectors? which must have been used in local campaigning.

During 1916 and 1917, the branch organised regular rallies on Peckham Rye, an established speaking ground, the early ones supported by a wide range of labour organisations, including the Marxist British Socialist Party, as well as Quakers and the Christian-pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. The local press reported attendances of 2-300, but after the first few months the papers lost interest, or rather, chose to ignore anti-war activity.

Other branch activity included putting watchers in place when COs came before military service tribunals, and placing pickets outside London prisons to keep tabs on the movement of prisoners. This intelligence fed into the Conscientious Objectors Information Bureau, the central record system carefully maintained by the NCF and its allies. NCF choirs sang regularly outside London prisons.

The Dulwich NCF booklet claims that 75 objectors from the area had been arrested by the date of its publication. Of the 63 men offered work under the Home Office scheme 28 had accepted, while 35 had refused and were serving repeat jail sentences. Of the 75, 27 were members of the ILP and 17 were “unattached socialists”.

Another second source of information about the branch comes from the memoirs of Clara Cole, entitled The Objectors to Conscription and War, published in 1936. A friend of Sylvia Pankhurst, Cole was a former suffragist who had moved to Camberwell with her husband, Herbert, a successful illustrator.

Her memoir quotes from a letter sent from Wandsworth prison at the end of the war:

“I feel sure I am expressing the feelings of many here who have been struck with admiration of your work and that small band of militant women workers around you… My mother … has never known such true fellowship and sympathy as that which she has received from all the many friends who have come forward to make her life a little cheerful through the sad times which she has had to endure.”

Cole herself pays tribute to Cahill who “worked unceasingly in visiting prisoners, taking up any and every task possible”. Women, it seems, were the branch activists.

In all, some 241 men from the present-day borough of Southwark refused the call-up on grounds of conscience. Of these, 47 were absolutists (figures drawn from the Cyril Pearce national database of COs on the Imperial War Museum website).

National movement

Anti-war activities in Dulwich need to be seen within several broader contexts: the domestic front in London; repeated military failure and its impact on British politics; and wider world events.

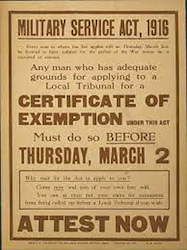

When introduced in 1916, conscription provided a focus for opponents of the war nationally, establishing a sort of front across the country between the government side, represented by the army’s conscription machine and the military service tribunals, and the anti-war movement, headed by the NCF and other anti-war organisations.

When introduced in 1916, conscription provided a focus for opponents of the war nationally, establishing a sort of front across the country between the government side, represented by the army’s conscription machine and the military service tribunals, and the anti-war movement, headed by the NCF and other anti-war organisations.

Most COs probably saw their refusal to bear arms as a way of taking a personal stand against the war. Bertrand Russell and others hoped their resistance might mobilise the desire for peace they believed to be latent in ordinary people.

He was disappointed, however, when all but a minority of objectors agreed to be moved into the less rigorous regime of Home Office camps. Moreover, once in a cell or a labour camp there was little more any CO could do to oppose the war, except for staging work strikes, which brought extra punishment.

Conscience cases only ever made up a fraction of applications for exemption that came before the tribunals, and after 1916 the number of COs declined, although the Fellowship remained very active in the first part of 1917 when its leadership threw itself into a national campaign to welcome the Russian revolution. This began with the Albert Hall rally in late March and led on to the Leeds Convention in June, which, among other things, called for workers’ and soldiers’ councils on the Bolshevik model to be established across the country.

Then the revolutionary impulse stalled: the NCF was seriously disabled by the partial withdrawal though exhaustion of its driving force, Catherine Marshall. It ceased to campaign against the war, at least until the German offensive of 1918, and concentrated instead on getting jailed absolutists out of prison.

Nationally, from mid-1917, COs were no longer in the forefront of resistance but part of a wider movement headed by the ILP and its energetic protégée, the Women’s Peace Crusade.

The Crusade was relaunched at a great demonstration on Glasgow Green in July 1917. With Ethel Snowden at its head, it became a major force in Scotland, the north and midlands, expanding over the following year to 123 local crusades, although there were none in London or the south.

The ILP’s growing branch network sold the Labour Leader, in which Philip Snowden wrote a front-page review, while the Herald, edited by George Lansbury, was also campaigning for immediate peace talks. The Herald League had branches too, although far fewer than the ILP.

A dedicated band of MPs – a mixture of ILPers and dissident Liberals – launched four peace debates in the Commons in 1917 from their outpost below the gangway on the opposition side. They also kept up a barrage of questions about the treatment of objectors.

Meanwhile, Lord Lansdowne, the former conservative foreign secretary, went public in his opposition to the war with a letter in the Daily Telegraph. He wrote in November 1917 that while Britain was not going to lose the war, its “wanton prolongation will spell ruin for the civilised world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it”. This was exactly the argument used by Lansbury and Snowden in their socialist papers.

A number of daily papers supported the letter, including the Manchester Guardian, the Yorkshire Post, the Birmingham Post, the Sheffield Independent, the Edinburgh Evening News, and in London the Daily News and the Star, although the Camberwell and Peckham Times denounced him as “Lord Letusdown”.

The breadth of the anti-war movement in the latter stages of the conflict was illustrated further the following year (1918) when the Women’s Peace Crusade called for Lansdowne, the ultimate Tory grandee, to head their movement.

My research has been an act of recovery, an attempt to salute and honour the men and women in my part of south London who played their part in this wider movement of opposition, people who stood out against what is now, by general consent, seen as the primal catastrophe that determined the whole course of the 20th century.

As the guns boomed out to mark the armistice, as the church bells rang and the crowds cheered, Creech Jones in Pentonville prison wrote that he wanted to creep away and weep. He saw in a gradual vision the tragedy and cruelty of it all, the despairing minds and desolate hearts, the fair joyous friends who had gone.

“In my secret heart I was glad that I had been able to hold firm & see it through. My protest against war was ‘my bit’, my contribution to the nation’s life & thought. Joy came to me that destiny had given me this work.”

—-

John Taylor has turned to history in retirement. Before that he worked for the Workers’ Educational Association, the Refugee Council and the Creekside Forum in Deptford.

John Taylor has turned to history in retirement. Before that he worked for the Workers’ Educational Association, the Refugee Council and the Creekside Forum in Deptford.

Against the Tide: War Resisters in South London 1914-16 and The Fight to a Finish: War Resisters in South London and Beyond 1917-19, both by JH Taylor, are available to download free here where you can also watch his talk to Sands Films in November 2021.