Colm Murphy’s engaging new book on recent Labour history is an invaluable companion as the party contemplates another return to power, says GARY KENT.

Labour thinkers have proposed various approaches to taming capitalism over the years, not least in the period covered by Colm Murphy’s Futures of Socialism, 1973-1997. His fresh take on the conflicts of those turbulent decades suggest some of the discarded ideas may still have life in them today.

Murphy “consciously reconstructs the intellectual and cultural world of the British left” at that time as it was “rocked by crushing defeats, bitter schisms and ideological disorientation”. Those years formed the first half of my activism and I recall multiple tracts about the sclerotic nature of British capitalism and “where now for the left” debates.

The long path to Labour’s victory in 1997 featured the flawed Bennite upsurge, the nearly terminal SDP split, Eurocommunism’s Gramscian perspectives, Ken Livingstone’s “rainbow alliances” at the GLC, the purging of entryist groups, Neil Kinnock’s policy changes, and the radical extension of those under Tony Blair.

The long path to Labour’s victory in 1997 featured the flawed Bennite upsurge, the nearly terminal SDP split, Eurocommunism’s Gramscian perspectives, Ken Livingstone’s “rainbow alliances” at the GLC, the purging of entryist groups, Neil Kinnock’s policy changes, and the radical extension of those under Tony Blair.

Murphy’s central theme is that there were “plural, contested and evolving meanings” in Labour’s modernisation, with prominent leftists accepting the need to overcome top-down statism. He uncovers rich debates on industrial democracy, constitutional reform, the changing shape and feminisation of the workforce, “a telling absence” on race and multiculturalism, and various economic models. This review in Renewal dives deeper into these themes than space allows me here.

Chapters on foreign policy, defence and Northern Ireland would have been handy, too, but you cannot have everything. He also omits the dramatic impact on the left of the coup in Chile in 1973, widely seen as a warning to radical governments of domestic and international reaction.

Murphy trawls “a deliberately diverse source base” including from Marxism Today, New Socialist (Labour’s theoretical magazine), the Labour Co-ordinating Committee, Charter 88, Demos, the IPPR and key thinkers such as Peter Hain, although he acknowledges that scholars can overstate the importance of noisy thinkers.

Sadly, he doesn’t include the ILP, which could have been noisier about the changes it pioneered in this period, such as electing leaders through an electoral college of members, MPs and affiliated bodies, and using one member one vote to select parliamentary candidates. It was demonised for opposing changes to the party’s constitution that artificially favoured the right or left, and for challenging some members’ romantic attachments to Irish unity and the IRA. Success on that issue for the ILP and others helped to encourage unionist support for the Belfast Agreement.

Seizing power

But my focus here is on economics. In the 1970s, the Alternative Economic Strategy (AES), including what became Lexit, was the main show in town. Its intellectual father was Stuart Holland, my university tutor – we used to swap LCC and ILP material. Its political patron was Tony Benn (pictured) who drove the AES through the party until it became the basis of the 1983 party manifesto, dubbed “the longest suicide note in history”.

The AES advocated protectionism, tripartite planning, nationalisation of many institutions including banks, and Lexit – often dubbed socialism in one country. Left writers hailed it, including Benn adviser Frances Morrell, who described it in 1981 as “a seizure of power over the City and over multinational business” and “the liberation of Britain”. A few years later, Morrell mocked leaders “who never tire of quoting dead heroes, mourning past defeats, and above all arguing for obsolescent economic and industrial strategies.”

The AES advocated protectionism, tripartite planning, nationalisation of many institutions including banks, and Lexit – often dubbed socialism in one country. Left writers hailed it, including Benn adviser Frances Morrell, who described it in 1981 as “a seizure of power over the City and over multinational business” and “the liberation of Britain”. A few years later, Morrell mocked leaders “who never tire of quoting dead heroes, mourning past defeats, and above all arguing for obsolescent economic and industrial strategies.”

Holland then advocated an Alternative European Strategy, supranational responses to globalising capital and the rapid rise of green politics. Holland worked with French Socialist Jacques Delors on a pan-European project that didn’t seem to inspire Labour Leader Michael Foot. But it impressed his successor, Kinnock, who turned the Eurosceptic tide and ended Labour’s support for unilateral nuclear disarmament in 1989.

The aim of the AES and its revision was to build countervailing power to an ever-changing capitalism and find funds for public services. And for the same reasons, Labour increasingly embraced globalisation as it was engineered by Mrs Thatcher and approved by the public at several elections.

In 2005 Tony Blair stated: “I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer.” He moved the focus from manufacturing to the commanding heights of education and training – “human capital” in the “information age”.

For Murphy, New Labour was never the doomed victim of Thatcherism and neoliberalism, as many on the left claim, but part of a “dynamic socialist and social democratic political culture” that “generated enduring institutions, forces and ideas that still shape Britain today”. It was less new than advocates and critics suggested and Murphy stresses its continuities with previous Labour regimes, in aims if not in means.

Benn also features heavily in the book as a dynamic leader who “immatured with age”, as Foot put it. He once divided politicians into “Signposts” and “Weathercocks”. The Signpost, he argued, constantly says: “This is the way we should go”, while “the Weathercock hasn’t got an opinion until they’ve looked at the polls, talked to the focus groups, discussed it with the spin doctors”.

Murphy shows this was and is a ridiculous caricature. Leaders sought to marry principle and reality, as they saw it. Sure, they tested options and opinions to seek how best to present them and win power.

And they weren’t all the same. One moderniser, Bryan Gould, proposed different a path when he stood for the leadership in 1992, including employee share ownership plans, but was defeated by a 91% vote for John Smith. Benn’s “barmy” leadership challenge in 1988, as the ILP described it, was smashed and split the left. Their ideas were overshadowed.

Stakeholder society

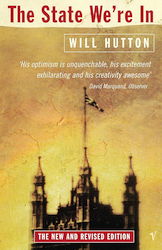

But nothing is ever entirely defeated if advocates build an informed base as times change. What goes around comes around. A major modernisation that fell by the wayside was the ‘stakeholder society’ championed in Will Hutton’s best selling 1995 book, The State We’re In, and briefly embraced by Blair before it was cautiously dropped.

Hutton’s ideas about “new forms of economic, social and political citizenship” are now returning to prominence. Industrial policy, once banished, has re-emerged, first haltingly under Theresa May, then with more purpose under Keir Starmer. It’s on the rise internationally too – the IMF records more than 2,500 industrial policy interventions worldwide in 2023.

Hutton’s ideas about “new forms of economic, social and political citizenship” are now returning to prominence. Industrial policy, once banished, has re-emerged, first haltingly under Theresa May, then with more purpose under Keir Starmer. It’s on the rise internationally too – the IMF records more than 2,500 industrial policy interventions worldwide in 2023.

This is because global supply chains dangerously sap the West’s resilience against hostile actors such as Russia and China. The lauded German model of manufacturing and exports was based on a long and fatal reliance on Russian energy imports and now the SPD is struggling to make sense of its Zeitenwende, turning point.

Britain cannot merely import commodities as it did before but must de-risk trade and fund greater self-sufficiency in strategic products such as tanks, steel, food and microchips in alliance with like-minded countries – on-shoring and friend-shoring.

Murphy was a toddler in Ireland in 1997, but that doesn’t diminish his fresh eye on “the diversity and creative ferment of the left” over these years. But attending Marxism Today conferences and reading LCC pamphlets were minority pastimes, as I often found when addressing CLPs outside London for the ILP.

I have darker memories than Murphy, of ugly faction-fighting as Labour forces imputed ulterior motives to bitter opponents; of quick-fix internal solutions to rig decisions; of the left taking voters for granted even as economic and political policies altered long-standing tribal voting patterns and hollowed out union membership.

Some were tin-eared. At a rally in 1976 with Harold Wilson, a Labour NEC representative applauded the trade unions’ “14 million workers and their wives”. It was bunkum then and became more so in the following decades.

Party conflicts in the 1970s were especially raw, partly because it was the last decade when a socialist society was deemed a feasible destination. Those who doubted the wisdom of such a vision were often depicted as interlopers. Many activists pursued maximalist motions in the empty shell of the party and kidded themselves pyrrhic victories would mobilise the working class, which was largely indifferent or hostile.

Things have got better and worse since then for Labour as a thinking party. It now formally defines itself as a “democratic socialist” party but is, in essence, social democratic, seeking to tame and civilise capitalism with, according to taste, timid or bold policies. The word “socialist” is saved for occasional rhetorical flourishes as when my old ILP colleague, Jon Trickett, concluded in 2022 that “socialism is the only real hope for humanity”, with no attempt at definition or strategy.

Sadly, debate can be worse now due to the polarising and sloganising impact of social media, populism and conspiracism. Although the internet has enabled online access to a wealth of material and meetings, organised political education is marginal, our collective memory is thin, and a deep superficiality haunts foreign policy issues. The refusal on principle of some on the left to debate controversial issues such as identity politics has limited our thinking.

Murphy concludes that: “In our unstable world, where developments in one corner of the world can, in mere weeks, transform everyday lives in another, a predilection to adaption and innovation is no bad thing.” He adds, perhaps optimistically, that “if suitably humble, pluralist and open-minded, social democracy’s tendency to revision may yet prove to be its blessing.”

Wider intellectual rigour is vital as Keir Starmer and Labour thinkers calculate the perennial need for balance between an active state, regulation and the market’s animal spirits, while facing new questions such as how to expand links with Europe without abandoning Brexit, the perils and promises of Artificial Intelligence, and the increasing risks of war and climate change.

Murphy’s engaging look at an often forgotten and distorted period in Labour’s past is an invaluable companion on that journey.

—-

Gary Kent is a foreign policy columnist for Progressive Britain and a Labour adviser in parliament.

Futures of Socialism: ‘Modernisation’, the Labour Party, and the British Left, 1973-1997, by Colm Murphy, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2023 and is available here for £24.99.