To mark its 120th anniversary this July, local member PAUL SALVESON celebrates the roots, birth and history of the Colne Valley Labour Party and examines its impact on the distinctive culture of the area

The Colne Valley CLP was formed on 21 July 1891 and put down deep roots in the Pennine communities of the Colne and Holme valleys. However, socialism didn’t just emerge, fully-formed, in 1891.

The roots of our movement lie in the radical weavers’ culture which flourished from the 1780s in the small rural communities dotted around Huddersfield and stretching across the Pennines towards Oldham. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and The Age of Reason were often to be found in hand-loom weavers’ cottages. Debates on the French Revolution, American independence, Ireland and political reform would often echo around the moorland pubs.

Following a short-lived period of relative prosperity among weavers, the introduction of power looms had led to a catastrophic decline in weavers’ living standards. An entire way of life was under threat and the response was violent. The ‘Luddite’ uprisings which took place around Huddersfield and the Colne Valley in 1812 were acts of desperation which were ruthlessly suppressed. The execution of several alleged leaders and followers – including a child of 12 – left a legacy of bitterness towards the establishment.

The failure of the Luddite uprisings helped to channel working class discontent into political channels. The great Manchester reform demonstration on 16 August 1819 was attended by tens of thousands of people including contingents from Colne Valley. Despite its peaceful intent the assembly was attacked by yeoman cavalry causing at least 17 deaths and hundreds of severe injuries. A banner condemning the atrocity was woven in Skelmanthorpe and kept hidden for generations. Now in the Tolson Museum, it bears the legend:

May never a cock In England crow

Nor never a pipe in Scotland blow

Nor never a harp in Ireland play

Till Liberty regains her sway

Strong support for radical reform continued in the weaving villages of the Colne Valley throughout the 1820s and 1830s, culminating in the great Chartist Movement of the late 1830s and 1840s. Once again the Colne Valley was prominent in the struggle, with women as well as men playing leading roles in the fight for ‘The People’s Charter’ whose six points demanded universal manhood suffrage, secret ballots, annual parliaments and equal electoral districts.

The movement ran out of steam by the late 1840s but many former Chartists remained active in the Liberal Party, republican and secularist movements, trades unionis and co-operatives. In the Colne Valley, however, trades unions in the 19th century were never strong reflecting the relatively small-scale nature of the woollen industry and its strong paternalistic ethos. In contrast, the co-operative movement was, and many of the original co-op stores remain today and provide an excellent service.

The Colne Valley constituency was first formed in 1885, although it has gone through several changes in shape and size since. For many years it included Saddleworth, now in Oldham East and Saddleworth constituency, and part of Oldham (Greater Manchester) – to the chagrin of many Yorkshire folk! At different periods it has included Denby Dale and Kirkburton parishes.

Socialism comes to the Colne Valley

The beginnings of national socialist organisation emerged in the early 1880s. The Democratic Federation, formed in London by the autocratic and upper-class cricketer HM Hyndman, became overtly socialist in 1884. It changed its name to the Social Democratic Federation and began to put down roots in the north, particularly in Lancashire. A couple of years later, some disenchanted members broke away and formed the Socialist League which had a branch in Leeds. One of the active members was Ben Turner, a young weaver from Holmfirth who went on to become a cabinet minister in the inter-war Labour governments and always kept his Holme Valley connections.

Early in 1891 a ‘Social Democratic Club’ was formed in the cellar of a terraced house on Nabbs Lane, Slaithwaite. Some local railway union activists met there and had the idea of setting up a more formal socialist organisation. A similar body had been formed in Bradford a few weeks earlier and the Colne Valley wasn’t going to be left behind.

On 21 July a small group met at the club and were addressed by Ben Turner and Allen Gee of the weavers’ union, plus James Bartley of the Bradford Labour Union. it was agreed to form a ‘Colne Valley Labour Union’ and its aims were:

‘To form a Labour Union on the lines of the Bradford Labour Union to be called the Colne Valley Division Labour Union for the purpose of securing independent labour representation on local bodies and in Parliament.’

The new organisation had an uphill struggle. The area was dominated by the Liberal Party although despite having substantial working class support (though many male as well as all female working class adults didn’t have the vote), the party had shown little interest in promoting working class candidates. Like many early ‘labour unions’ the Colne valley organisation was not explicitly socialist and wanted to appeal to the Liberal-inclined workers.

It has often been assumed that the rise of socialism in areas like Colne Valley owed much to its nonconformist tradition. That’s only true in part. Methodism helped to give a suitable organisational structure to the early Labour Party but many Methodists were anti-socialist. As many, if not more Anglicans supported the early socialist movement as did nonconformists.

Putting down roots

The new organisation built up a strong body of support through an extensive network of clubs, social events and meetings. Slaithwaite Labour Club was formed in 1892 with Golcar’s established shortly afterwards. Within months there were clubs formed in Honley, Marsden, Milnsbridge and Longwood. The clubs were centres of political and social activity and most, if not all, were ‘dry’ – they didn’t serve alcohol. This was part of a strong tradition of working class temperance which took decades to disappear. Honley Socialist Club, established in 1907, remained tetotal until after the Second World War.

The first major political breakthrough came in 1892 when George Garside was elected to West Riding County Council for what was essentially the current Colne Valley electoral ward. He was the first socialist to gain a seat on a county council in Britain and won in a straight fight against the Liberal, gaining 55.1% of the vote. The following year saw the formation of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in Bradford, and the Colne Valley Labour Union immediately affiliated. The ILP developed a distinctive form of ‘ethical socialism’ which stressed socialist values and fellowship and had a particularly strong base in the West Riding.

Tom Mann was selected as the CVLU’s parliamentary candidate to fight the 1895 election although the result was regarded as disappointing, despite polling 1245 votes against the sitting Liberal Sir James Kitson’s 4276. The Tory came second with 3737 votes. Despite this and other setbacks, the CVLU gradually built up its representation on local bodies, including the Board of Guardians, which controlled the poor law provision, and the school boards. In the same year as George Garside’s county council victory, Tom Quarmby was elected unopposed to Linthwaite School board.

Political meetings became a common feature of Colne Valley life and were attended by huge crowds. For example, on 25 February 1894 Tom Mann addressed a gathering of 900 people in Delph on the subject of ‘Labour Politics’. Women speakers such as Katharine St John Conway (later to become Mrs Katharine Bruce Glasier), Isabella Ford, Margaret Macmillan, Caroline Martyn and Enid Stacy were hugely popular. During one of Katharine’s visits to Slaithwaite in 1893 she was presented with a gold pen and handkerchief by women members of the CVLU.

Socialist life in the Colne Valley was much more than just political meetings. During the summer every branch organised garden parties, rambles in the surrounding countryside and concerts in the burgeoning number of labour and socialist clubs. The annual procession each July, organised by the constituency party, became more of a gala event with brass bands, choirs and games. In the winter months, teas and social events took place. The strong musical tradition in the Colne Valley was eagerly exploited, with socialist choirs and even a brass band formed in Milnsbridge, in 1908. Cycling became immensely popular in the 1890s, with bikes becoming affordable to working class men and women. Inspired by the socialist newspaper The Clarion, a network of cycling clubs were established which were closed linked to the ILP and its local organisations like the CVLU. Marsden had a Clarion Cycling Club for many years.

Nationally, the unions and the ILP came together to form the Labour Party in 1900; it was a federal organisation with a number of affiliated trades unions and socialist societies including the ILP. Until 1906 it was called the Labour Representation Committee. At the general election that year it won 26 seats, the first real electoral breakthrough for Labour, although it was decided not to stand a candidate in Colne Valley as there was an informal pact with the Liberals.

Victor Grayson: socialism triumphant

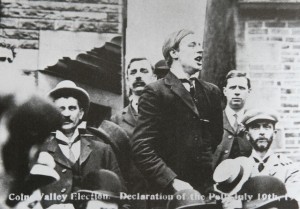

Victor Grayson was a popular figure in the socialist movement of the early 1900s. He was young, handsome and a charismatic speaker. The Colne Valley Labour League (as it had been re-named in 1900) decided to adopt Grayson as its parliamentary candidate following the 1906 election when the party didn’t stand. Labour’s opportunity came when Sir James Kitson, the long-established Liberal MP for the constituency, was elevated to the House of Lords. They seized it with both hands despite opposition from the ILP and Labour Party at a national level.

Grayson’s election campaign was more like a religious revival. Huge crowds attended open-air meetings throughout the constituency, on both sides of the Pennines. One observer said: ‘He seemed so enthusiastic about everything…. It was infectious, it really was. People just went haywire. They went mad at his meetings, they could grip them.’

His election manifesto was a radical statement of socialist aims. He said: ‘I am a socialist and believe there can be no freedom or security for the working classes while the Land and Means of production are owned and controlled by a small privileged class.’ He continued to detail a number of specific reforms, including the right to work, old age pensions, votes for women, land nationalisation, education for all, free trade, and abolition of the House of Lords.

The campaign had an electrifying effect on the Colne Valley with daily rallies, meetings and processions. Grayson swept to victory with a majority of 153. The Daily Express ran the headline: ‘Today the Red Flag flies over the Colne Valley’. There are stories of weavers decorating their looms with red ribbons showing their support for ‘Our Victor’ in defiance of employers who feared it was the start of a revolution.

Grayson was MP for three years, spending much of his time touring the country promoting the socialist cause. He was an erratic MP and attracted criticism even from his supporters, and he was suspected of having a drink problem. He lost the seat in 1910, although he won a respectable vote. He was increasingly unpopular among the ILP leadership and took the Colne Valley Labour League out of the ILP in 1911, re-branding it as ‘The Colne Valley Socialist League’, affiliated to the newly-formed British Socialist Party.

War and after

The years between 1914 and 1918 saw socialists deeply divided over whether to support or oppose ‘The Great War’. Huddersfield and Colne Valley was a centre of opposition to the carnage and many socialists and non-conformists went to prison for their anti-war beliefs.

The 1918 general election saw the Colne Valley Socialist League, now re-affiliated to the ILP and the Labour Party, run Wilfrid Whiteley as its candidate. Whiteley attracted criticism from some quarters for having opposed the war but polled a very respectable 9473 votes. This laid the basis for victory in 1922 when Philip Snowden, another anti-war campaigner, won the seat with a majority of 1282 votes, driving the Liberal into third place behind the Tory. A further election the following year saw him increase his majority.

Labour formed a minority government supported by the Liberals, and Snowden was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. The government proved short-lived and was back in opposition less than a year later. But Labour had shown it was fit to govern and Snowden remained as MP.

The following years saw the country become increasingly divided as Baldwin’s Conservative government drove down working class living standards and supported attempts by employers to reduce wages. The upshot was the General Strike of 1926 when major industries, including railways and engineering, ceased operating for nine days as workers supported the miners. The miners remained out for several months and the government introduced anti-strike legislation.

The bitter aftermath of the General Strike helped to consolidate Labour’s working class support. The general election of May 1929 saw the party win 289 seats and Snowden trebled his majority in the Colne Valley. He was once again appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer and Ramsay Macdonald re-assumed his role as Prime Minister.

Despite its best-ever result, however, the party did not have an absolute majority and had to rule with the acquiescence of the Liberals. The economic situation deteriorated and Snowden pursued a rigidly orthodox approach which today would be called ’neo-liberal’. The ‘Wall Street Crash’ in America had much the same effect on the world economy as the recent financial crisis.

In Britain unemployment rocketed and the party was split over how to respond. A majority of Labour MPs favoured socialist measures based around strong state intervention but Macdonald and Snowden sided with the Tories and Liberals in sticking to right-wing orthodoxy. A split became inevitable, with Snowden and Macdonald forming an alliance with Tories and Liberals to create a ‘national government’. Labour was wiped out, holding on to just 52 seats despite a fairly respectable overall vote.

Colne Valley was lost to the Liberals and Snowden was reviled as a traitor, a very sad end for a man who had done so much to create the socialist movement as we know it today.

—-

Paul Salveson’s new book, Socialism with a Northern Accent – radical traditions for modern times, will be published later this year. More information from www.paulsalveson.org.uk

This is adapted from a new booklet called Looking Back, Looking Forward: Colne Valley Socialism 1891-2011 published by Colne Valley CLP to celebrate its 120th anniversary. Copies are available from 21 July for £3.95 including postage from: CVLP, 90a Radcliffe Road, Golcar, Huddersfield HD7 4EZ. Cheques payable to ‘Colne Valley Labour Party’.

For details of the Colne Valley CLP 120th anniversary celebrations click here.

To read the second part of Paul Salveson’s history of Colne Valley CLP, click here.

12 December 2015

Dear Paul,

I am currently doing research on my Grandad, Willie Lumb, of Colne Crescent, Marsden who was a member of the ILP, and Marsden Socialist Club, and a committee member of Marsden Adult School. I have some of his books, including the speeches of Victor Grayson and other works by J S Mill and the Webbs. I also hold his letters and postcards from France, where he served with the Machine Gun Corps in the Haut Somme(Retreat of the Germans to the Hindenberg Line). Then at Passchendaele, and finally at Saulcourt, where he was captured on 22nd March 1918 during the German’s final push, Operation Alberich. He was held in Dietkirchen, Hesse, and treated OK by the Germans, and was able to write home through the Red Cross in Holland. I would be grateful if you could provide any info from ILP records of his involvement, or suggest where I could direct my efforts. Many thanks in anticipation

Jo Blanchfield