Johnny Dent died of cancer on 29 January 2012 in St Cuthbert’s Hospice, Durham. A member of the ILP for many years, and a staunch trade unionist, he played a major role in organising support for the striking miners in Durham during the 1984/85 dispute.

He was also a member of Ex-Services CND and active in the Save Consett Steel campaign of the early 1980s. The son of Communist Party parents, he was anti-authoritiarian by upbringing and over the years joined countless of marches and demonstrations for a variety of causes.

Born above a shop in Durham Market Place on 21 June 1923, he had numerous jobs throughout his life, including butcher, baker, navy commando, truck driver, mechanic, coal merchant, pipe layer, electrician’s mate and university police officer.

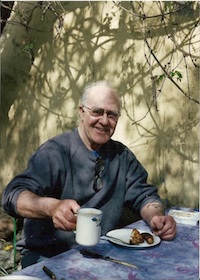

But most of all he was a beloved comrade, a man of deep humanity, compassion and loyalty. At his funeral on 6 February, his friend HUGH SHANKLAND gave this moving tribute to ‘the strongest man I’ve ever known’.

—

Johnny, how lucky we’ve been to know you.

That song, The Joy of Living, is by Ewan MacColl, whom Johnny knew well, and who wrote it toward the end of his own long and rich life, paring it down to the absolute essentials, two vital instincts: the adventurous appetite to explore and discover life for oneself, and the strong need to connect with others in love, companionship, and family.

How powerfully those contrary instincts were lived out within Johnny you would feel above all when on the road with him: first the drive to push on, on and on into the unknown, toward adventure, and then, mounting as the distance grew, the pull back, the longing for home. One long night Johnny drove from northern Italy right across Switzerland. The next day he wouldn’t let me take over, sat behind the wheel right across France, eating up the miles that kept him from Durham and [his wife] Nora.

How powerfully those contrary instincts were lived out within Johnny you would feel above all when on the road with him: first the drive to push on, on and on into the unknown, toward adventure, and then, mounting as the distance grew, the pull back, the longing for home. One long night Johnny drove from northern Italy right across Switzerland. The next day he wouldn’t let me take over, sat behind the wheel right across France, eating up the miles that kept him from Durham and [his wife] Nora.

His love and his loyalty were immensely strong. His marriage was a love affair that lasted a lifetime. When even Nora’s perception of everything in the world but him finally started to abandon her it was a wonder to witness how hard he worked to bring her back to him, even for just a second or two in twenty hours at her bedside, to not let the illness completely beat them.

The night of [his daughter] Norma’s birth, when the roads were impassable due to heavy snow, he trudged through the blizzard right out to Winterton hospital near Sedgefield, and Nora said she looked up from her bed to find her Johnny standing there in a great puddle of water, an unbelievable happy apparition. And after kissing his wife and his baby he walked the whole way back.

Despite his tormenting insomnia and headaches, his perpetual howling tinnitus, his failing health and strength in these last years, and Nora’s gentle but long decline, Johnny would still say ‘I’ve had a good life’ and totally mean it.

‘I had a lot of energy,’ he said in one of our last chats, ‘and I used that energy.’

In fact, and in every sense, Johnny was the strongest man I’ve ever known.

Even at seventy, even at eighty, his physique was exceptional, his handshake was strong and warm, his hug was huge, as huge and generous as his capacity for friendship.

His courage was strong, and of course tested in battle, and many times over. Johnny was present at every beach assault during the Italian campaign, right from Sicily to Anzio. His compassion was strong too, he stood by his friend Lofty Gordon when his nerve broke after they’d come through the hell of Salerno together. The war was the great adventure of Johnny’s life, and it gave him his abiding love for Italy.

His political convictions were strong, and he lived them with typical pragmatism. When Nora’s carers complained of their lot he had no sympathy, he told them to join a union. No authority intimidated him. In this, his greatest influence was his father, who gave him his politics but also independence of mind at a time when the perversest forms of nationalism were raging but when, too, the ideal of solidarity between working people right across the globe seemed more straightforward than now, and perhaps achievable. It was a sustaining optimism that despite all the evidence of history never entirely left Johnny – as we will be reminded today when we leave this room.

By conviction and on principle Johnny was a communist and a socialist (I don’t think he made the least distinction between the two, in their purest form), but by inclination he was a free spirit. How else could he have told with such relish how he and his wild bunch offloaded the stores from a ‘Yank’ supply ship while their mates got the guard drunk on Pusser’s rum in the skipper’s cabin, or how he and Ivor and Lofty ingeniously depleted NAAFI warehouses first in Tangiers and then in Messina.

What great stories Johnny had. His memory was strong, formidably strong, and he loved to share it: he seemed to remember every road he ever drove, every load he ever carried, every horse he ever backed. He had the born storyteller’s freshness of observation and delight in human quirks, and the born storyteller’s epic sense of the joy of living.

He was strong-minded too, of course, but that was because he believed, rightly, that he was gifted with an exceptional mind, and he believed a good sound mind has the capacity and the duty to debunk what he called ‘the rubbish kit’ convention saddles us with and find its own path to wisdom in the confusing but exhilarating school of life. He was a fighter but never looked for a fight, for he had too much self-control. But if challenged, like a good boxer, he could keep his nerve and think on his feet, and unimpressed by his opponent’s bluster suddenly floor him with a deflating joke.

Even when confronted by the most powerful adversary of all Johnny kept his nerve and his sense of humour. Precisely four years ago he was given at the very most six months to live, and he left the consulting room saying: ‘Goodbye, doctor, see you next Christmas.’ He went on to live, as we all know, not one but another four Christmases, and despite at least three serious operations still managed to get back again to his beloved Sicily, and to Turkey, and twice to Spain.

Even in his last days in the hospice, intermittently, Johnny still showed bursts of that energy he spoke of as his defining characteristic – enfeebled and pumped full of drugs he could still suddenly rebel against passivity, restless and untameable. By a stroke of luck the view from that beautiful wide window was of the very same woods and fields he roamed all over when he was a boy.

But now, Johnny, this last little bit of time we had left together is all used up and the moment has come to say on behalf of us all, ‘Farewell, and ‘Thank you’.

Because you gave us a good ride.

Thank you Johnny, and farewell.

Grazie e ciao, Giovanni. Ti volevamo bene.

We loved you, Grandad Sticks, Cannonball, Nora’s best pal, and dearest companion.

Goodbye.

31 March 2012

We were priveleged to know this wonderful man and will never ever forget him. He did a great many things and helped so many people but it is his stalwart support, humour, passion and friendship we’ll particularly remember from when my parents Dot & Bob went through the Miner’s Strike of 84/85. He was a good friend to them. Hugh’s words are wonderful, we were not able to hear them in person so it is a comfort and an honour to read them here