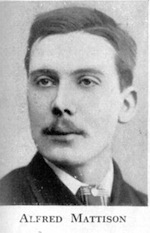

A lifelong ILPer, Alf Mattison is best known as a local historian, and for his Leeds Labour archives, the source of much material on the movement’s early years in the city. MICHAEL MEADOWCROFT seeks to rescue the man from the footnotes.

Socialism has always needed its scribes and its archivists. Alf Mattison was both, and without him Labour history in Leeds would be much the poorer. Virtually every account of socialism in the 19th and early 20th century uses Mattison’s diaries and notebooks but never dwells on Mattison the man.

He became involved in the tribulations within a tiny band of Leeds socialists following the split of the Socialist League from the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) in 1885 and was present at the inaugural ILP conference in 1893. He remained with the ILP after its disaffiliation from the Labour Party in 1932 and, despite his lifelong involvement and activism, Mattison remains a shadowy figure, always in the background.

Alf – always ‘Alf’ and never ‘Alfred’ – was born in Hunslet in 1868, the son of a locomotive engineer and the grandson of the lockkeeper at Thwaite’s Lock at nearby Rothwell. His mother was from Huddersfield where she had been in the textile trade. Alf was the third of eight children (one other child had died in infancy) and was the elder son. The whole family were squeezed into back-to-back houses until, in the mid-1880s, they were able to move to a through terrace, still in Hunslet.

By this time Alf was apprenticed to the engineering trade at the same workplace as his father. His father died in 1890 but Alf remained an engineer for a further 16 years until he became a clerk in the city’s tramways department. Whilst at the Hunslet Engine Company he was part of a seven month lockout of engineering workers.

Mattison had an early experience of political activism when in December 1877, at the age of nine, he was present on Hunslet Moor when a crowd of 40,000 gathered to support and assist an agitator in the campaign to make the Middleton Railway remove a line laid across the moor, regarded as an infringement of the rights of commoners.

He attended the local Jack Lane school and at the age of 11 began work as a half-timer in a wool mill. Two years later, in 1881, as an inquisitive teenager, Mattison was on the edge of the huge crowd gathered to hear Gladstone speak at the Coloured Cloth Hall – roughly on the site of today’s Leeds City Square – and managed to fall through the railings. He was then transported over the heads of the crowd to the front of the rally.

One Sunday afternoon early in 1886, walking through the centre of Leeds, Mattison arrived at Vicars Croft, a space by the central market noted for its open air speakers:

“…. my attention was attracted by a pale but pleasant-featured young fellow, who in a clear voice was speaking to a motley crowd. After listening for a while I began to feel a strange sympathy with his remarks, and – what is more – a sudden liking for the speaker; and I remember how impatiently I waited for his reappearance on the following Sunday. A few months later and I joined ‘the feeble band, the few’ and became a member of the Leeds branch of the Socialist League.”(1)

The young man in question was Tom Maguire, a remarkable individual and a mythical figure in Leeds socialism. Only a couple of years older than Mattison, he had, entirely through his own reading, arrived at socialist views and secularism. He eked out a living as a photographer’s assistant but his main occupation was as a writer and poet for socialist journals. He gave three open air lectures every Sunday, plus two or three others during the week.

In 1884 Maguire had joined first Henry Hyndman’s SDF and set up a branch in Leeds. Hyndman was too autocratic for many of his erstwhile followers and the Leeds party split to set up a Leeds branch of the Socialist League, an organisation inspired by the socialist and somewhat mystical William Morris. All this is painstakingly recorded by Mattison, and the published histories duly follow his lead and trace the evolution of socialism in Leeds as if there was a large party. In fact, Mattison records that when they took stock of their Socialist League branch there were precisely 18 of them.

Maguire died of pneumonia at the age of 29 in a house lacking any means of heating and without any real food. Mattison was one of the two comrades who had gone round to his house to find out why he had not turned up for a meeting. He records movingly in his diary the immediate efforts they made to secure fuel and food, but he continues:

“It is to the everlasting regret of his friends that help and succour did not come to him sooner. The probability is that he might have been spared longer.”(2)

Maguire’s funeral was a remarkable event with 400 mourners accompanying the coffin on foot from his home in Burmantofts, while a thousand were present at the cemetery. Mattison was one of the speakers at the service. Maguire’s death was a huge blow to the Leeds socialist movement and it made it vulnerable to the excessive influence of demagogues such as John Lincoln Mahon.(3) It was up to Mattison and a few others, such as fellow engineer Arthur Shaw, to hold the group together.

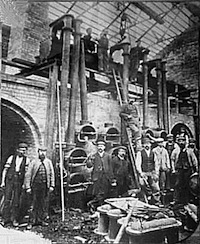

Gasworkers’ strike

Five years before Maguire’s death he and Mattison had been instrumental in providing the logistical underpinning to the organisation of the Leeds gasworkers who were fighting against the Liberal-controlled city council’s attempt to reduce their pay and increase their working hours.

Throughout his life Mattison invariably took on secretarial duties – and those of election agent – rather than being a ‘frontline activist’. He clearly recognised that this was his metier and it was certainly vital to the work and he was respected by his colleagues.

Incidentally, his wife Florrie, whom he married in 1902, was completely different. Always the fiery activist, she stood unsuccessfully four times as a municipal candidate and managing to be expelled from the Labour Party in 1952 at the age of 75 for going on a peace movement visit to Moscow sponsored by an organisation that, according to Labour, was Communist-led.(4) Towards the end of her life she did join the Communist Party.

The 1890 gasworkers’ strike was a seminal event in Leeds political history, dealing a blow to the Liberal Party which eventually proved fatal to its chances of retaining working class support. It also undermined the local Liberals’ skilful agent and ‘fixer’, John Shackleton Mathers, who was remarkably influential in getting the Leeds Liberals to adopt Labour men as candidates and magistrates.(5)

The 1890 gasworkers’ strike was a seminal event in Leeds political history, dealing a blow to the Liberal Party which eventually proved fatal to its chances of retaining working class support. It also undermined the local Liberals’ skilful agent and ‘fixer’, John Shackleton Mathers, who was remarkably influential in getting the Leeds Liberals to adopt Labour men as candidates and magistrates.(5)

Hitherto the Liberal-dominated trades council had inhibited unskilled workers’ unions joining it, but the success of the strike now made that virtually impossible and the complexion of the Leeds Trades Council was definitively different thereafter, although the Lib-Labs – chiefly William Marston, Owen Connellan and John Judge – fought a rearguard action again outright socialists such as Walt Wood, Alf Mattison and others.

The gasworkers had suffered reverses before Leeds and it was vital for the union’s future that the outcome in Leeds was different. Maguire chaired and Mattison was secretary of the embryo union branch in Leeds, ensuring that it was efficiently run.

They were crucial, together with Tom Paylor, in ensuring solidarity and in balancing militant tactics with an attitude of reasonableness designed to retain public sympathy, but it was the ineptitude of the Liberal council leaders – largely moribund after being in control of the municipality for 55 years – that handed the workers an important success. After three ‘dark’ days, the council backed down and the strikers were reinstated with their previous pay and conditions restored.

Mattison invited the London dockers’ leader, Will Thorne, to come to Leeds to speak for the strikers. He went to the railway station to meet the London train but somehow missed him. Mattison went home to wait for the next train only to find that Thorne had made his own way there. Mattison’s mother said to him, “There’s a strange looking rough man waiting for you in the sitting room. I can’t tell a word he says. I don’t where you pick up your friends.” She was amazed to learn some years later that this “rough man” had been elected to parliament.

The young Mattison’s scholarly talents within the Labour movement had been noted and he was regularly invited to spend time with a fascinating quartet of fairly rich middle-class intellectual socialists. If Maguire was his inspiration, his guru was Edward Carpenter, and his mentors were Isabella Ford, John Lister and Charles Oates. The latter four were all technically single people, though Carpenter had a long-term partner, one George Merrill. Carpenter remained a lifelong friend and there is a largely unmined trove of correspondence between them. Lister and Oates clearly enjoyed Mattison’s company and, from Mattison’s diaries, this was reciprocated.

All four of them had large houses, two in Leeds, one in the Peak Distrcit and the fourth on the outskirts of Halifax, and they all invited Mattison to stay with them. Both Lister and Oates also took Mattison on extended foreign tours. For what it matters, there have been lingering views that Mattison was also homosexual, and it might be significant that he did not marry until he was 33, and remained childless, but this is merely circumstantial. There is no hint, even veiled, in his papers that he pondered this. Rather, there’s a certain naïvety and gratitude towards his older and more middle-class benefactors.

Leeds ILP

After the 1890 gasworkers’ action, the next crucial date was 1893 and the formation of the national Independent Labour Party (ILP). In 1892 Maguire, Mattison and Mahon had begun to form Leeds ILP branches and Leeds sent seven delegates to the inaugural ILP conference in Bradford. Maguire, Mahon and Mattison remained well known, and a fourth, Frederick Marles crops up occasionally later, but the remaining three are – to me at least – unknown, oddly for individuals attending such a significant national conference. It is interesting that in a 1926 interview Mattison chooses his words carefully, saying that he was the only Leeds delegate, “still alive or active”.(6)

Typically, Mattison did not speak in the debates at Bradford, the Leeds delegates leaving this task mainly to Mahon, who, for once, kept largely to the consensus view agreed in Leeds.

It is interesting that the modest circumstances of local ILP officers did not inhibit them from offering hospitality to ILP leaders and from it being accepted. Keir Hardie was just one ILP leader who visited Mattison’s home and who thereafter always asked Mattison how his mother was whenever they met or corresponded.

Local ILP activities continued in Leeds and Mattison was involved in helping his workmate and friend, Arthur Shaw, fight the Leeds South constituency in 1895, although it was the ILP’s poorest result in Yorkshire. Mattison was also the honorary secretary of the local Fabian Society group and was involved with the Labour Church group in the city. Mattison records in his notebook that “faithful Tom Duncan was the mainspring of the Labour church here”. This is the same Tom Duncan, a manager in the Pygmalion department store on Boar Lane in the city centre, who was described by the Leeds suffragette, Mary Gawthorpe, as “our Keir Hardie”.(7) In 1919, he became Labour’s first Lord Mayor.

At one Labour Church meeting Mattison recalls that they sang a William Morris song which concludes: “’Tis the people marching on”, although he comments, “I’m afraid the people – other than ourselves – were very slow in joining the march.” It was at the Labour Church that he met his wife, Florence Foulds, and her sister Emily. Florrie was 11 years younger than Mattison and always emphasised that she had been a member there since 1897 and was a socialist before she met Alf. She was a tailor’s machinist by trade.

From 1900 the ILP was subsumed for electoral purposes into the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) and Labour candidates began to be successful in Leeds from 1903 – significantly a decade later than in Bradford – and the Labour movement was at last basically united. There were occasional flurries from other groups, such as the SDF in Armley in 1909 when Bert Killip stood and, although polling only 168 votes, deprived the retiring Labour candidate, a furious Owen Connellan, of his seat. By 1913 Labour had more elected city councillors than the Liberals, although the latter’s over-representation in Aldermanic seats masked Labour’s huge electoral improvement.

Parliamentary progress was slower and Labour’s first general election success in Leeds – James O’Grady in East Leeds in 1906 – came in a straight fight, courtesy of the secret Macdonald-Gladstone pact. Typically, Mattison’s role was as agent for Arthur Fox who finished second to the Liberal in South Leeds.

Local history

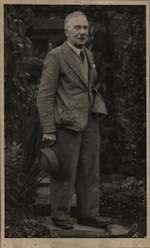

By this time Mattison’s other great interest – local history – was taking an increasing amount of his time. This passion was evident as early as 1897 when he was giving talks in Hunslet, but it had developed rapidly and he records a total of 35 lectures in 1905. He still maintained his open affiliation to the ILP – he was a lifelong member, including after the disaffiliation from Labour in 1932 – but he no longer took on official positions.

In 1908 he published a book, The Romance of Old Leeds, with the journalist Walter Deakins, containing photographs by Mattison himself. He was in great demand as a lecturer and feature article writer and became a committee member of the prestigious local history group, The Thoresby Society, in 1908.

In July 1917 there was a remarkable Peace Convention in the Coliseum in Leeds, called by a joint committee of the Labour Party and the British Socialist Party, to celebrate the first Russian revolution and to call for action to emulate it in Britain. Mattison records:

“I just dropped in as Ramsay Macdonald was speaking. The place was packed and the atmosphere charged with the greatest enthusiasm. I went to the evening meeting. It was a gigantic affair – packed in every part – there would be close on 3,000 of an audience.”(8)

Mattison regularly wrote and lectured on Leeds Labour history(9) and was very jealous of his role in the formative years. When John Badlay, a somewhat theatrical early Labour councillor, asserted that he had been involved “from the beginning”, Mattison quickly contradicted this, saying that Badlay had “only” been active from 1895.

In addition to all his notebooks and press clipping files, Mattison did a great service to Labour historians by maintaining an archive of leaflets and flyers throughout his political career. In September 1929 Edward Brotherton personally bought the whole collection with a view to it being housed in the Leeds University library that bears his name. It is a very valuable source of ILP and other Labour movement material today. Perhaps typically, Florence gave Alf’s diaries and remaining papers to the Leeds public library rather than to the university.

It is clear that Mattison maintained contact with his old friends, including Macdonald and Philip Snowden even after the formation of the National Government in 1931. He wrote of Macdonald in his diary that, “Though he was guilty we cannot question his integrity.”

Mattison became increasingly deaf and his death came at the age of 76, on 9 September 1944, when he was knocked down by a tram on the approach into the centre of Leeds. From the evidence it appears that he did not hear the tram approaching. A witness stated that he was crossing the road “in a somewhat absent-minded manner, not looking to right or left”.(10)

Alf Mattison was an unusual politician. He was a dedicated socialist but a reluctant activist. We know that he was immensely loyal and spoke on behalf of the cause in local parks throughout his life, but his great, and more congenially personal, contribution was as the movement’s ‘squirrel’, maintaining an invaluable record of the history of socialism in one major city.

Alongside this he was an inveterate gatherer of photographs and material on Leeds generally. He was a Leeds man, not particularly interested in the national scene – his name appears just three times somewhat randomly in the ‘Reformers’ Year Book’ list of contacts(11) but he certainly deserves to be given flesh and blood rather than be consigned to reference footnotes in histories of the Labour movement.

—-

Notes and sources:

1. Tom Maguire – A Remembrance, Labour Press Society, 1895

2. Entry for 8 March 1895, The Mattison Papers, Special Collection, The Brotherton Library, Leeds.

3. For Mahon see his entry in Volume3 of Biographical Dictionary of Modern British Radicals, ed J O Baylen and N J Grossman, Harvester Press, 1988.

4. See A veteran’s voice for peace, Florence Mattison, Labour Monthly, August 1953

5. See, for instance, his remarkable statement to local Liberal MP Herbert Gladstone shortly before the gasworkers’ action, quoted page 26 of Nourishing the Liberty Tree, Liberals and Labour in Leeds, 1880-1914, Tom Woodhouse, Keele University Press, 1986.

6. “Rank and File Personalities, No 6, The Socialist Review, September 1926. (My emphasis)

7. p179, Up Hill to Holloway, Mary Gawthorpe, Traversity Press, Penobscot, Maine, 1962.

8. Notebook C, Alf Mattison Papers, Special Collections, Brotherton Liberal, University of Leeds; for a report on this remarkable event, see British Labour and the Russian Revolution, Documents on Socialist History: No 1, Spokesman Books, nd. The Leeds delegates were Bertha Quinn and D B Foster.

9. See for instance, the series of articles in The Leeds Weekly Citizen between 4 January and 26 April 1918.

10. Yorkshire Post, 11 September 1944.

11. The Reformers’ Year Book, 1902, 1907 and 1908, ed. and published Joseph Edwards.

Michael Meadowcroft is a Liberal politician. He was a Leeds city councillor from 1968 until 1983, and was Liberal MP for Leeds West from 1983 to 1987. He has written extensively on politics and political history. His archive is available on www.bramley.demon.co.uk.

This article is taken from a lecture on Alf Mattison given at The Leeds Library on 18 November 2013.

See also: Tom Maguire – A Leed Pioneer, by John Battle.