BARRY WINTER calls for a ‘declaration of interdependence’ to guide us through these turbulent and tumultuous times.

Writing recently in the Independent, Steve Richards captures some of the drama of the era we are living through.

We are experiencing “tumultuous” and “challenging times”, he says, adding that our society has been “engulfed by explosive political and economic crises at the same time”. He speaks of a “whirlwind of events” and focuses on how British politicians are responding.

Richards’ account provides a useful complement to what I want to say here in what is an experimental attempt to understand what’s happening to all our worlds. I am at the early stages of developing these ideas, so there are plenty of rough edges.

One could easily broaden Richards’ argument and go global referring to the so-called Arab Spring; the middle class protests in Israel against declining living standards; India’s movement against corruption; the growing discontent in China; and, of course, the Occupy movement which has spread to 1,000 towns and cities. We should also note the emergence of the global Avaaz movement, our home-grown version, the 38 Degrees petitioners, and UK Uncut, which has been occupying banks and shops from Fortnum and Mason to Top Shop.

One could easily broaden Richards’ argument and go global referring to the so-called Arab Spring; the middle class protests in Israel against declining living standards; India’s movement against corruption; the growing discontent in China; and, of course, the Occupy movement which has spread to 1,000 towns and cities. We should also note the emergence of the global Avaaz movement, our home-grown version, the 38 Degrees petitioners, and UK Uncut, which has been occupying banks and shops from Fortnum and Mason to Top Shop.

While it would be wrong to suggest these political events all have the same causes, and each has to be understood within its own context, it is possible to identify some shared, underlying processes at work.

To try to assess what’s taking place, I want to suggest that we are experiencing three interlinked crises which feed into and off each other: a social crisis, an economic crisis and a political crisis.

Then I want to touch briefly on the nature of power in relation to current political struggles, drawing on ideas about visible and invisible power, and to suggest how an understanding of these ideas may help us to respond. In addition, I will consider some aspects of the very visible Occupy movement, including its struggles to create space for democratic politics.

Finally, I will suggest some political ideas that may help in formulating a progressive way to meet the challenges we face in these dangerous times. Here, I’ll make use of the ethical notion of ‘interdependence’ (as opposed to both independence and dependence).

Three questions

There are three questions I want to ask.

1. Where are we and how did we get here?

For this, I will draw on a critique and periodisation of the last three decades.

2. What is happening?

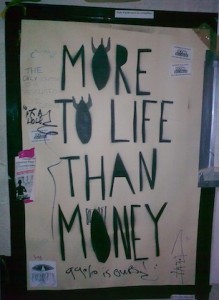

I want to suggest that, amid the huge shifts taking place, there are great dangers and real fears. But there are also some important opportunities that need to be grasped. In particular, elite power has been partly exposed by the crises and found wanting on a large scale. At the same time, democracy is playing second fiddle to the markets, to market power, and to the continuing rule of money.

3. What might be done?

Here the aim is to examine possible pathways out of the various interlocking crises. These alternatives need to be based on a moral critique of our world, and on ethically-based forms of left politics. For me, that means valuing many of the new movements for change but seeking to link them with actually existing political parties (a point that merits a much fuller consideration than is offered here).

Let’s start with a quote from the recently deceased writer and academic, Tony Judt. His book, Ill Fares the Land, while sometimes contentious, is none the less an impressive and persuasive review of contemporary life.

He begins: “Something is profoundly wrong with the way we live today. For thirty years we have made a virtue out of the pursuit of material self-interest: indeed, this very pursuit now constitutes what remains of our collective self purpose. We know what things cost, but have no idea what they are worth.”

He adds: “The materialistic and selfish quality of contemporary life is not inherent in the human condition. Much of what appears natural today dates from the 1980s: the obsession with wealth creation, the cult of privatisation and the private sector, the growing disparities of rich and poor. And, above all, the rhetoric which accompanies these: uncritical admiration for unfettered markets, disdain for the public sector, the delusion of endless growth.”

Of course, Judt was not unique in his awareness that modern society is deeply flawed, that something is seriously wrong. Many make similar claims from across the political spectrum, albeit with different explanations and solutions. However, I think Judt points in some of the right directions and would commend the book to anyone interested in reviving a morally-based, social democracy as the path to take.

I share with him the view that the last three decades have generated a moral vacuum, that ours is a culture which encourages isolated and self-serving individualism. The goal is to be rich, by whatever route, to declare and preserve one’s supposed independence, one’s detachment from the rest of society. And let the devil take the hindmost.

You can see where this leads on a daily basis, not least in popular culture. We have a good laugh at those poor unfortunates whose dreams lead them to make fools of themselves on programmes like the X-Factor, that popular theatre of cruelty. Their desire for fame and fortune reflect our society’s dominant aspirations.

Of course, those who do make a fortune believe they should keep all the proceeds because they did it all on their own. This is a society in which the rich go to great lengths to avoid paying taxes while many denigrate those who make false welfare claims. Meanwhile, no banker’s bonus can be too high or executive wage increase too large. Their rewards, they claim, are based on their “superhuman talent” for moneymaking. As George Monbiot points out, the evidence for this claim is somewhat lacking, but that does nothing to deflect its advocates.

The result for our society is massive inequality with all the socially corrosive effects that has, not least on young people. The riots were perhaps one symptom of this, the anger of the excluded and devalued.

Gideon Rachman, chief foreign correspondent of the Financial Times, provides a more analytical approach to what he calls our “troubled times”. In his recent book, Zero-Sum World, he identifies three distinct periods during the three decades referred to by Judt.

Rachman describes 1980-91 as the ‘age of transition’. These years witnessed the rise of a new right committed to liberalising economies and rolling back the state in response to the failings of the post-war settlement. The seeds of the economic crisis we face now were sown in this decade, particularly in 1986, the year of the Big Bang in the City, which released capital from many constraints triggering the pursuit of massive profits.

Rachman sees the period from 1991 until 2007/8 as an ‘age of optimism’ following the fall of Communism. These years (with some setbacks) were the high point of neo-liberal self-assurance as the right reshaped the world in its image, with the United States leading the way. ‘Things can only get better’ as the theme tune adopted by Tony Blair’s New Labour put it.

Since 2007/8, we have entered an ‘era of crisis’ with political and economic elites struggling to respond to events, seemingly inadequate to the challenges they confront. No-one appears capable of riding to the rescue, so they call in the supposed technocrats (many with links to Goldman Sachs).

As the Observer put it: “The only power world leaders have is to frustrate each other. The failure of the G20 summit has dramatically advertised the incapacity of the political elite to rise to the crisis.”

Crises and instabilities

This brings me to the crises we need to understand to help explain our current instabilities.

A crisis is perhaps best understood as a tipping point when events can change dramatically – choices have to be made, directions taken, and the world changes in important ways. In a crisis there are no simple ways of going back to what you had before, but it can take years before matters are resolved one way or another. Crises are moments of both opportunity and risk.

At present, we are experiencing three interlocking crises.

First, a social crisis, which some depict as a social and/or cultural recession. David Cameron’s notion that we are a broken society is a partial recognition that something is wrong. More profoundly, Jonathan Rutherford and the Labour MP, Jon Cruddas, talk about the “fragmentation of social life”.

For what it’s worth, I use the term ‘dis-located society’, one where the many social bonds between people, and between people and their institutions, have been dislocated, damaged or even cut, where the bonds between people and the natural world are strained, and, no less importantly, links between people and their histories are severed. The past becomes a lost terrain and people become prisoners of the present, something which forecloses on the idea that we might be able to shape a better and more generous future.

Put differently, the notion that we live in a shared world is declining, the idea that there is a common good which we can achieve together has faded. Ironically, the only time recently when I’ve heard a politician say we are all in this crisis together is when it is manifestly not true. Some float above our problems on oceans of wealth.

The English Defence League may be one response to this sense of loss of history and identity. Its supporters wrongly identify and blame Islam as the cause of this loss. Theirs is a cry of pain and anger, of nostalgia for a world that has gone, and rage at living in a world in which they have no purchase, no place and no value. Interestingly, many are football supporters whose clubs have become the property of the rich. The EDL attracts those who have lost their sense of belonging to society; outsiders who believe they have somehow been cheated of their rightful legacy. Their response is hideous and dangerous, but that should not blind us to its roots.

The rot in society – the moral decay – is becoming increasingly obvious at the top from where it sprang: the world of big money, big media, corrupted politicians and compromised senior police officers. In recent months all this has become more evident than it has been for a generation or more. It has entered the public realm and become part of everyday conversations.

We also have a political crisis. The first coalition government for 65 years is a symptom of this after the electorate rejected Labour without showing much enthusiasm for the Tories. This should be seen in the context of a longer-term growing disenchantment and cynicism towards politics and politicians, reflected most obviously in election turn-outs.

This disillusionment is reproduced elsewhere in liberal democratic states, including the US, parts of the Europe, and towards the European Union itself. And it takes even stronger forms in some authoritarian states where there is a growing hunger for democracy.

The political crisis is also clearly linked to what has been happening in the world economy. Our economic crisis follows the triumph of market utopianism, a period of out of control turbo-capitalism with its lunatic speculative frenzy.

Will Hutton argues that the economic crisis is due to “excessive competition”, to a form of “rank bad capitalism”. He says that bankers and financiers knew that in playing the system they could socialise the losses and privatise the profits. They grew their balance sheets by stunning amounts.

Alongside that we have seen the steady growth of what Guy Standing calls the ‘precariat’, a growing mass of permanently insecure, low-paid workers. This is most obvious among young people, whose futures look bleak regardless of their qualifications. A million young people in the UK are now jobless, yet the political director of the Taxpayers’ Alliance told Sky News “they should be getting jobs instead of protesting”. Who pays his wages, I wonder?

Power and visibility

In our society the power of the strong has been largely invisible, discreet, more hinted at than observable. It is a power that operates behind the scenes, with nods and winks, through private conversations, with lobby groups, via networks of privately funded institutions.

One sign that such power is being challenged is that we are now starting to get glimpses of what’s been happening for years – whether it’s bankers’ bonuses becoming public knowledge, or the media’s machinations, or how formal politics operates.

I learned recently that one in four or five people with permanent passes to the House of Lords are lobbyists for private interests. Washington is notorious as a home for major financial and business interests, based there to influence US politicians. It’s a huge but largely invisible empire.

Monbiot has been arguing that think tanks and lobby groups are the bane of democratic politics. They are the means by which corporations and the ultra-rich influence public life without having to reveal their hand. Their refusal to reveal their funding, and the British state’s failure to demand it, are deeply undemocratic. Nigel Lawson’s anti-climate change organisation is but one example of a group that declines to indicate who funds its activities.

Monbiot says that the Liam Fox scandal is “enmeshed in a web of corporate influence about which we know little”. Thanks to the efforts of some journalists, the curtain has been lifted, slightly.

Monbiot argues: “Today, sponsorship by millionaires explains why free market think tanks outnumber and outspend think tanks arguing for public services and the distribution of wealth… These organisations wield great influence in public life. But we have no means of discovering on whose behalf they do it.”

But the fact that they are more exposed is, at least, a start. As he says, “the undeserving rich are now back in the frame”.

In contrast to the power of the strong is the countervailing power of the weak, the power of the many, the 99 per cent. It has to seek visibility to gain a hearing; it has to occupy and demonstrate, to keep up the pressure, and to mobilise people. It only happens when people feel deeply moved to step out of their ‘normal’ lives. It can be tiring and demanding, as well as exciting and empowering. Like waves, it ebbs and flows.

It’s what the journalist, Madeleine Bunting, calls the “slow burn of new perceptions and new questions” which open up new political possibilities. “It is about seeding questions in people’s minds,” she says.

This need for visible power brings us to the Occupy movement which, by October, involved 950 actions in 82 countries, sparked by earlier movements in Spain and other Mediterranean nations, and linked to events in Tunisia and Egypt (now experiencing its second wave of struggle). In the Middle East, the struggles were against dictatorships which introduced neo-liberalism with all its insecurities and instabilities.

Here, Occupy stands in contrast to another occupation – the invisible and quiet occupation of land in the City of London by private corporations. More and more land is being quietly privatised, making land ownership an important political issue again.

As Dan Hind wrote on the Open Democracy website: The aim [of the Occupy Movement] is to create a venue for democratic deliberation and open debate in a place normally associated with secretive privilege.”

It’s slogan, “We are the 99%”, is powerful and succinct. Bunting describes the activities she found during her visit: “Everywhere there is the hum of strangers talking to each other about politics, accompanied by a sense of relief that finally people have a space.”

The protest is raising a debate about the prospect of putting the morality back into capitalism. As one contributor to a recent Observer discussion asked: “How can we we organise social and economic relations in a way that promotes some understanding of the common good, so that we recognise our deep dependence on one another?”

Let’s not underestimate the spread of this debate. Even the Financial Times, for example, says: “Today only the foolhardy would dismiss a movement reflecting the anger and frustration of ordinary citizens from all walks of life around the world… the fundamental call for a fairer distribution of wealth cannot be ignored.”

A declaration of interdependence

This brings me to the notion of ‘interdependence’, a morally-based concept that is increasingly securing an airing, although it has been around for some time. I begin by offering a few quotes which bring out the points I want to make.

Will Hutton writes: “I think the agenda for getting out of [the crisis] is a recognition that there is a co-dependency between the public and the private. Excessive competition is self-destructive.

“Obviously, wealth generation comes and is driven by entrepreneurship and most of that comes from the private sector. But the private sector does not exist in a kind of social vacuum or a public vacuum. It is co-produced with the public sector. You need tax revenues to invest in universities, to build ports, infrastructures, railways.”

Andrew Rawnsley says: “The Greek economy is just 2% of European GDP and an even tinier portion of global DP. That one slight country could dominate a summit of Earth’s mightiest [the G20] was a reminder – if anyone needs reminding – of the interconnectedness of the world. An infection that starts somewhere small can quickly spread to places which are much bigger.”

Mike Rustin puts it like this: “This system has failed through the instabilities of unregulated markets, the result of what happens when the power of property and capital are unrestrained by relations of interdependency and reciprocity with other social forces, or by governments which represent their interests.”

Our society has been hell-bent on promoting independence at all levels, from to the personal to the national. We have lost sight of a crucial truth: no-one is really independent, no family, no community, no society, indeed no nation state, nor the EU or the US. We watch the Tories demanding that EU leaders sort the Euro crisis while refusing to help, even though our economy depends on it hugely with half the UK’s exports going to the EU.

In the 18th century the US produced a Declaration of Independence. Today we need to declare our interdependence; and this should be a guiding feature of the world we live in, from the personal to the international.

As Rutherford and Cruddas put it: “The task of living necessitates interdependency with others, and this interdependency leads to questions of equality and justice”.

In the 17th century the poet, John Donne, wrote: “No man is an island”. Updated to include women too, this should be the motto for better times.

Of course, there are some who will fight this idea tooth and nail, often to preserve their powers and privileges, but we are the 99%. Our lives interact visibly and invisibly with others; we are linked to each other by many threads. Universities exist because past generations fought for a right to education that was denied to them. We may be fighting for that again.

No social gain, no advance is permanent. We need vigilance if we are to defend the reforms we have won (and to honour the memory of those who fought for our benefit). As long as we have markets and capitalism, there will be a need for countervailing forces to prevent their excesses.

In that way, we pay our dues to generations as yet unborn, not just ourselves. The world they inherit is being made now. To learn from the errors of recent decades, we have to begin to recognise that we are not just individuals but part of wider interdependent collectivities.

It would be a small step in the right direction. And, at the moment, small steps could just provide a pathway towards a better future.

—-

This is based on a recent talk to the Politics Society at Leeds Metropolitan University.

Click here to read Markets, Movements and Morals, Barry Winter’s review of Tony Judt’s Ill Fares the Land.

‘Moral capitalism: It’s Miliband who captures the mood of the times’, by Steve Richards, was in The Independent on 8 November 2011.

Gideon Rachman’s Zero-Sum World: Politics, Power and Prosperity after the Crash is published by Atlantic Books.

‘Ethical Socialism’, by Jonathan Rutherford and Jon Cruddas, was published in Soundings, 44, Spring 2010.

Guy Standings’ book The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, was published in 2011 by Bloomsbury.

17 January 2012

[…] foundation’s first chair is Barry Winter, a retired politics lecturer from Leeds, and he makes the initial focus of campaigning clear: A […]

17 January 2012

[…] foundation’s first chair is Barry Winter, a retired politics lecturer from Leeds, and he makes the initial focus of campaigning clear: A […]