6: Thatcher & Beyond

The Thatcher years

Under James Callaghan, the Labour government came to a humiliating end in 1979. Its defeat followed a fierce battle with public service workers in the 1978/79 ‘winter of discontent’. The Labour government, which had won office five years earlier promising a partnership with the unions, came to grief trying to impose a stringent pay deal on some of the county’s most poorly-paid trade unionists.

Under Margaret Thatcher’s leadership, the Tories campaigned to defeat the organised working class, to curb the unions and to give vent to free markets forces in an effort to stimulate economic growth.

The Thatcher regime is often seen as marking a clear break with post-war consensus politics based on full employment, Keynesian economic management and expanding welfare provision. But this masks the way in which the previous Labour government had begun the process. It was a Labour government which laid the basis for this swing to the right, not least by singling out the unions as the major cause of the country’s economic ills.

Indeed, the Labour opposition found that whenever they tried to criticise the Thatcher government’s policies, Tory ministers easily rebutted them. The Tories simply recited Labour’s own record in office.

What Labour had done under pressure – cuts in the health service, social services and in local government, monetarism, selling public assets – the Tories undertook with vigour and a new ideological zeal. for there reasons, the ILP argued that past Labour governments had in effect acted as the political midwives to ‘Thatcherism’.

Internal Strife

Labour’s election defeat led to a period of bitter in-fighting. The Labour right tried to shift much of the blame for the result onto the actions of public sector unions in the winter of discontent. This conveniently overlooked how for three years trade union leaders delivered wage restraint. Only when they could no longer resist the pressure from hard-pressed union members did this change. The right also ignored the Labour government’s own record and the damage that it had done.

In return, the left concentrated its fire upon the undemocratic nature of the party and lack of accountability of MPs and party leaders. A momentum for reform developed within the party and in this heady and sometimes exciting atmosphere, many on the left expected far too much from these reforms. They saw them as providing a short-cut to transforming the party.

They seemed to believe that if mandatory selection and leadership elections were introduced, right-wing MPs would be replace wholesale by left-wingers. In other words, they acted as if the left were poised for a genuine victory and that this would win support in the working class and in the wider society. Perhaps this optimism derived from the greater flexibility of the block vote. A small group of key trade union leaders were for a time more open to persuasion from the left. This outlook was reinforced when leader right-wingers broke away to set the Social Democratic Party. The social democrats also seemed to believe that now that the block vote was not so easily at their disposal the game was up for the Labour right.

At the same time, many left wingers began to favour the block vote because it appeared to be working in their interests. The ILP regarded this not only as lacking in principle but politically short-sighted. For the ILP, no fundamental political change could take place in the party if it rested on the block vote’s paper battalions. Political transformation would take decades. It had to be based on a real, large-scale grass roots movement and not a thin layer of activists.

The ILP’s political differences with an increasingly confident Bennite left coalition, organised for a time in the Rank and File Mobilising Committee, came to a head in response to the right-wing counter attack. The Bennite left pinned its hopes for changing the party upon constituency delegates who they saw as more radical than the wider membership and therefore more likely to remove offending right-wing MPs.

Once the Labour right knew that they could no longer resist mandatory selection of MPs by constituency delegates, they argued that it should be on the basis of one party member, one vote. They hoped that the less radical members would outvote the ‘activists’. Correctly seeing this as a cynical device to blunt the left’s progress, the Bennites countered by insisting that such decisions should be in the hands of constituency delegates.

The ILP stood almost alone on the left at this time in arguing that it was very wrong to oppose the principle of one member, one vote. To do so, it argued was to abandon the moral high ground. Moreover, before any real change could be contemplated individual party members had to be won. If the left could not convince the party membership of its views then it could no hope to win wider public support.

For these reasons, the ILP proposed that one member, one vote should be embraced as a principle. All party members who had attended at least three branch meeting in the preceding 12 months should be eligible to vote. Such a reform would also help to encourage a more informed, participatory membership.

But this was not the ILP’s only difference with the Bennite current. Sadly, in their enthusiasm to wrest control of the party from the right, many of that left ignored the fact that what was going on in the party did not really reflect developments in the wider labour movement, still less among the working class which was becoming increasingly disturbed by those inner-party conflicts (as the election results were to show).

Attempts by the ILP to warn the left of its increasing isolation, and of the need to adopt a less confrontational approach on party reform, were angrily dismissed by them as a sign of political weakness. To suggest that for socialists the block vote was something of a problem, rather than the way forward, was treated as heresy.

In these inner-party battles, the Bennite left appeared to carry all before it, securing mandatory selection and, at the special Wembley conference in 1981, an electoral college with the highest proportion of votes going to the trade unions. But for the ILP, these apparent victories contained the seeds of the subsequent undoing of the Bennite movement. It allowed space for a right-wing counter attack and for the introduction of one member, one vote by postal ballot.

In resisting one member, one vote the Bennites lost a great deal of credibility and allowed the Labour right to reclaim some lost ground. Tony Benn’s bid for the deputy leadership in 1981 was narrowly defeated but it became increasingly clear the block votes cast for him did not reflect the views of the union membership – quite the contrary. The ILP considered that the Bennite ft had built its house on shifting sands, that it had no mass support and that as a result it would begin to crumble under the impact of external events.

Eric Preston argued in the ILP publication, Labour in Crises, that the ILP does not want its “politics to be dependent on the manipulation of the block vote. We are not out to secure 51 per cent of the votes of imaginary people in an effort to introduce an individual into any position of authority. We cannot achieve what we are about by some transient change which reflects noting very much elsewhere in the movement.

“If we are to achieve socialism, it will be the result of a long and complex struggle to root socialist ideas and practices among a large and growing party membership. And when that had been achieved, we must anticipate an equally long and hard struggle to win majority support for socialist measures among the wider labour movement and the working class.

“The process is neither as chronological nor as mechanistic as this outline suggests. But the salient point is that the building starts within the Labour Party and necessitates some coherent, reasonably disciplined and avowed socialist political organisation or organisations, determined to work democratically for the long term goal of a Labour Party and a Labour Party leadership committed to socialist polices.”

Neil Kinnock’s Leadership

It was the shock of the 1983 general election defeat, when Labour’s total vote slumped dramatically, which led to a major split in the Bennite left. The ‘soft’ left regrouped round the newly-elected party leader, Neil Kinnock. Confident of their own strength and influence, they saw themselves as being well-placed to ensure that he remained on the left.

In contrast, the ‘hard’ left, now led by the recently-formed Campaign Group of MPs, identifies Neil Kinnock as the enemy who had to be exposed. They saw their purpose as rallying the opposition to the new leadership, warning party members that he did not represent their political outlook and that he would betray them. In their world, what stands between the Labour Party and a socialist Labour government, is a leadership that refuses to embrace radical left policies and take them to the people.

The ILP suggested a quite different approach to both. It saw the election of Neil Kinnock as a sign of the serious crises gripping the party; that labour’s long-term failure to politicise its support in society now meant it was in a trap of its own making.

In the circumstances, should Labour leaders try to move the party to the left in a society hostile to left ideas, when it would be defeated. On the other hand, if in trying to win electoral support Labour moved to the right, this would reinforce public hostility to radical ideas and undermine the party’s long term prospects.

For these reasons, the ILP did not share the optimism of those soft lefts who thought they could keep Neil Kinnock on a radical course. It was far more likely that those who tried to do so would become prisoners of the constraints that were acting upon him. Events would influence them far more than they would influence events.

Nor did the ILP believe that the party leader was unrepresentative of the party membership. Instead it stressed that Neil Kinnock reflected the feelings and aspirations of the broad membership far more than the left did. Therefore appeals to party members to change the leadership would be self-defeating. They would only isolate the left from the wider membership who desperately wanted a Labour victory. This would only strengthen the party leadership’s grip. For that reason, the ILP did not support the Benn-Heffer leadership challenge in 1987 when the hard left suffered a massive defeat.

Under Neil Kinnock’s leadership, policies which were seen as being electorally unpopular were dumped. The party leader strained every nerve to ensure that nothing that might disturb the voters would remain and, assisted by the block vote, he fought a tough fight to impose his political authority on the party.

The ILP & the Left

During the Kinnock years, the ILP continued to develop in ways that were quite distinctive from much of the Labour left. This did not come from any partisan desire to be different simply for the sake of it. Rather, it was because it found very few who shared its political perspectives on the Labour Party and social change. As a result, the ILP’s campaigns, politics and style often set it apart, although, wherever possible, it tried to establish a dialogue with others.

On Northern Ireland, on the register of party groups and Militant, on resisting cuts in local government, on black sections, on defence and nuclear disarmament for example, it often differed radically from both the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ left approaches.

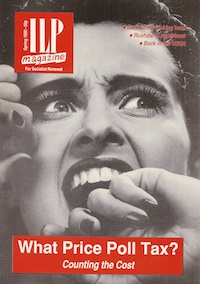

The ILP also threw its energies into supporting the miners strike of 1984/5. It campaigned vigorously against the Tories youth training scheme and for a labour movement boycott. It was one of the first groups to organise the opposition to the poll tax: seeking to unite those willing to undertake civil disobedience with those unwilling to risk illegality.

In the process, the ILP began to attract a new generation of members firmly committed to socialism but who recognised that socialists operate in a hostile conservative culture. Socialists who support the Labour Party but who are critical of the way that Labour leaderships having failed to challenge social conservatism have thereby reinforced it. Socialists who identify with what is sometimes called the ‘third road’ socialism which combines parliamentary and extra-parliamentary means to social change.

In the process, the ILP began to attract a new generation of members firmly committed to socialism but who recognised that socialists operate in a hostile conservative culture. Socialists who support the Labour Party but who are critical of the way that Labour leaderships having failed to challenge social conservatism have thereby reinforced it. Socialists who identify with what is sometimes called the ‘third road’ socialism which combines parliamentary and extra-parliamentary means to social change.

The ILP has sought to appeal to those who recognise the need for political coherence as well as concern for the human condition and who believe that that morality is an essential ingredient of socialist politics, including class politics.

For them, the demise of what passed for socialism in Eastern Europe, the crisis of the labour movement in Britain, are not taken as signs that socialism is a lost cause but that it needs to be renewed on more solid foundations from the base upwards. A new kind of socialist politics needs to be created.

Of course, that is easier said than done. The crucial question then is how is it to be done. For the ILP, there are no simple blueprints. No political group has all the answers but we can begin to outline what a renewed socialist movement might look like.

1993 & Beyond

As ILP members began to approach their centenary year, they felt that it was necessary to do more than commemorate the event. It was also felt to be vital to assess the scale of the task now facing socialists in the coming decades. This meant acknowledging the sad truth that many aspects of socialism are in crisis (even though the term ‘crisis’ is much overused).

The crisis has many origins. But much can be attributed to historic failure of the labour movement to politically educate its support among the working class. People have been starved of any understanding of the nature of capitalism and fed instead on the ideological outpourings of the right-wing forces in our society. People are wary of anything that smacks of politics and afraid of anything that is defined as extremist.

In other words, the gulf between socialists and the working class is a wide one. The question is how to bridge it: how to take socialist politics to people; how to make it relevant and relate to their concerns and activities; how to win respect and trust, if not outright agreement; how to win friends and allies among people who will not, for whatever reason, wish to join; how to make a moral appeal.

None of this assumes a high level of class consciousness. Indeed, it assumes the opposite. But it does recognise that a huge potential exists.

For these reasons, the ILP is to relaunch itself in 1993 to contribute towards that process. This means that it is taking up a challenge similar to that faced by the socialist pioneers. In a sense, this means we are starting all over again. But in doing so, we can draw upon a century of experience.

Of course, none of this is enough. We also need to understand the world if we are to change it. Part of that understanding, however, can draw strength and encouragement from the ILP and more particularly from the many thousands of women and men who in spite of the odds, not only saw the need to change the world but did something positive about it.

—-

This is an extract from the original centenary edition of The ILP: Past & Present, published in 1993. The print version is now sold out.

This is an extract from the original centenary edition of The ILP: Past & Present, published in 1993. The print version is now sold out.

The latest revised and updated version, published in 2023 to mark our 130th anniversary, is available to buy in two parts from our publications section.