WILLIAM KNOX charts the devoted life of ILP leader James Maxton, “a special kind of orator who inspired human beings to struggle for socialism”.

James Maxton was born on 22 June 1885 in Pollockshaws, Glasgow, the son of James Maxton, schoolteacher, and Melvina (née Purdon), a former school teacher. At the time of Maxton’s birth, his father was earning £90 a year as an assistant master in Pollock Academy, and the family lived in a three-roomed house. However, five years later Maxton was appointed headmaster of Grahamston School, Barrhead, and here Maxton attended school until the age of 12.

In 1900 Maxton won his first prize at Barrhead Free Church Sunday School for Scripture. In the same year he won a scholarship from Renfrew County Council to attend Hutcheson’s Grammar School, Glasgow, for three years. There he excelled in sport, particularly athletics and fencing, and also passed the Hutcheson’s Trust Scholarship examination, which allowed him to continue his education as a pupil teacher on an annuity of £15.

In 1902 Maxton’s father died and his educational progress was temporarily halted. Both he and his sister were forced into work as pupil teachers. Maxton found a post at the Martyr’s Public School, in the Townhead district of Glasgow. Later that year, he entered the Glasgow Teacher Training College and matriculated as a student at the University of Glasgow.

It was during his early days at university that Maxton entered politics. However, it was as a member of the university’s Unionist Association; as such he “gave his first political vote to George Wyndham as Conservative candidate for the lord-rectorship”. Maxton also joined the university’s 1st Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers. In his second year, he became a member of the SRC and was a member of the editorial committee of the university magazine; he was also a noted half-mile runner.

It would appear that at this point in his life Maxton was merely a conventional product of a lower middle-class background. But there were signs that he was becoming restive over his complacent acceptance of the norms of Edwardian Britain. Much of this was due to the influence of John Maclean of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF).

Maxton attended open-air meetings in Paisley and came under Maclean’s spell. He later said that “it was Maclean who influenced him most and who was responsible for his conversion to socialism”. Contact with the SDF encouraged Maxton to read some of the socialist classics, such as Robert Blatchford’s Merrie England and Britain for the British, Peter Kropotkin’s Fields, Factories and Workshops, and Henry George’s Progress and Poverty.

One of the first signs of Maxton’s growing rejection of his conventional Unionist political background was his decision to become an ambulance man, rather than an infantryman, in the 1st Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers. He also decided to join a university socialist study circle. It was as a member of this informal gathering that he was introduced to the work of Marx, whose analysis of capitalism and theory of value he embraced, but, as he said later, not his materialist conception of history.

ILP propagandist

However, what influenced Maxton to make up his mind to join the ILP was hearing Philip Snowden speak in 1904. That year he joined the Barrhead Branch of the ILP, where he found himself almost immediately elected literature secretary and, in a few weeks, acting as a propagandist on behalf of the ILP at outdoor meetings. Before long he was speaking almost nightly, sometimes two or three times at weekends, and this continued throughout his adult life, in spite of his membership of the Commons.

A few years later he was elected to the secretaryship of the branch and the Renfrewshire ILP Federation, whom he represented on the Scottish Divisional Council. In 1912 he was elected Scottish representative on the National Administrative Council (NAC) of the ILP, and from 1913 to 1919 he served as chairman of the Scottish ILP.

Around the time of joining the ILP, Maxton was forced through poverty to quit university and earn his living as a teacher in Pollockshaws Academy. He later enrolled as a part-time student and in 1910 graduated with an MA – of which he was very proud and constantly referred to. But it was while at Pollockshaws that he resumed his acquaintance with Maclean when both men were involved in teaching in evening school. Maxton and Maclean devised a course, under the title of “citizenship and the social sciences”, using Das Kapital as the set text. Needless to say when it was brought to the attention of the educational authorities the class was soon ended.

And it would appear that, apart from assisting briefly as a tutor in Maclean’s economics classes in Glasgow’s Central Hall, Maxton had little to do with Maclean after this episode. No doubt his membership of the ILP and his adoption of the constitutional road to socialism made Maxton an opponent in Maclean’s eyes, as he favoured revolutionary action and was a member of the British Socialist Party.

Maxton, at this time, was also increasingly drawn into trade union affairs. After three years at Pollockshaws he transferred to St James’ School, Bridgeton, one of the poorer districts of Glasgow. In these socially deprived areas teachers in elementary schools worked under intolerable burdens – classes of 70 or 80 children were not unusual.

Maxton, in response to these onerous conditions, joined the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS) and the Scottish Class Teachers’ Association, and was duly elected on to the national councils and Glasgow district committees of both organisations. Later, he and others formed the Glasgow Socialist Teachers’ Association, which acted as a kind of rank-and-file pressure group within the EIS for educational reforms.

Maxton’s views on education were a product of his socialist humanist outlook. To him socialism “was a complete philosophy of life extending to all spheres of human relationships and with particular emphasis upon the development of human personality”. Therefore, in Maxton’s view, a child was not to be seen as a piece of malleable plastic but as a living organism whose growth, mental and physical, was dependent on the correct amount of nourishment. A teacher, he argued, “was not to teach but to assist the child to learn”.

However, given that education could not, in a class-divided society, be divorced from other social problems, he concluded: “that the existing system of industrial capitalism based upon the virtual subjection of the whole of the working class prevented, not only the development of the educational system … but any other form of social and political emancipation.”

As a result Maxton decided to “devote all his life and energy to the task of socialist work and propaganda”. A manifestation of Maxton’s unhappiness of what he considered to be a repressive educational system, was his refusal to allow his son, James, to attend “the prisons called schools” until he was 12 years old.

Anti-war struggles

Although Maxton had become prominent in the ILP, reaching membership of the NAC as Scottish representative, he was still largely unknown outside of Glasgow. It took the First World War to change him from anonymous activist to a figure of national importance and popularity. As the war progressed Glasgow became the focal point of anti-war struggles in Britain, mainly because here, unlike other parts of the nation, the anti-war movement was firmly linked to the industrial struggle.

The shop stewards’ movement on Clydeside had strong links with the Glasgow ILP, in spite of the fact that only two of the leaders were members. The relationship had been forged during the Glasgow Rent Strike of 1915, when ILPers, such as John Wheatley and James Stewart, took an active role in the defence of the rent strikers in eviction cases. With the conversion of leading CWC member, David Kirkwood, to the ILP, it began to dominate Clydeside politics, and this increased as the war wore on.

As a political opponent of war Maxton was ordered to appear before the Barrhead military tribunal in March 1916. He explained his pacifist views to the tribunal and assured them he would continue to oppose the war. Maxton also pointed out that his appointment at Finnieston Public School had been curtailed because of his anti-war stand. The tribunal offered him the chance to join the Royal Army Medical Corps but Maxton turned it down. On his refusal the tribunal adjourned his case for a fortnight.

Between the time of adjournment and the date set for re-appearance Maxton was arrested and charged with sedition. On 26 March he had spoken at a meeting on Glasgow Green in protest against the deportation of Kirkwood and other leading Clydeside shop stewards. At the meeting Maxton advised the workers to down tools in support of the deportees, and repeated the plea for the benefit of the police in the crowd. Four days later he was arrested at his home in Barrhead by four policemen and taken to Duke Street prison. It was while incarcerated in the Glasgow gaol that Maxton became engaged to Sarah (Sissie) McCallum, later Mrs Maxton.

After pleading not guilty to a charge of sedition before Sheriff Lyall in Glasgow Sheriff Court, Maxton and fellow prisoner, James MacDougall, were sent to Edinburgh to stand trial at the High Court. The trial began on 11 May 1916 and, on the advice of their counsel, both men pleaded guilty to the charge of “attempting to impede, delay, and restrict the production of munitions by statements which they made during a demonstration on Glasgow Green”. For doing so both Maxton and MacDougall were sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment in Calton Jail, Edinburgh.

Maxton was released from prison on 3 February 1917. During his time in the Calton Jail, he had worked as a joiner repairing stools and tables. He also worked on the warders, convincing a number of them to form a branch of the Police and Prison Warders’ Union, and a few of them to join the ILP. However, in spite of his political successes with the warders, imprisonment proved something of an ordeal for Maxton. For although he did not suffer the mental anguish of John Maclean or John W Muir, Maxton’s spell in prison took its toll physically. The monotonous diet of porridge was one of the “contributory reasons for the severe illness which followed his release”.

Later that month Maxton was called to re-appear before the Barrhead military tribunal. Once again refusing to fight, he was given the opportunity to engage himself in work of national importance, but Maxton would not agree to aid the war effort. In the event he was found work as plater’s holder-on with a firm of barge builders for neutral countries by John Scanlon, of later Labour fame. While working there Maxton devoted his energies to supporting the Women’s Peace Crusade and to John Wheatley’s housing campaign for £8 cottages for workmen.

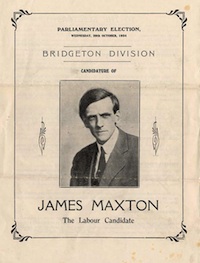

At the end of hostilities in 1918 Maxton stood as ILP candidate for Bridgeton in the ‘coupon’ election, although he had originally been nominated for Montrose Burghs, but he was defeated by the Conservative candidate, A MacCallum Scott, whom he later converted to the ILP.

His disappointment was, however, mediated to a degree by his appointment, in early 1919, to the post of Scottish organiser for the ILP at £5 a week; his election to membership of the executive of the Labour Party; and by his membership of the Glasgow Educational Authority (GEA), which he resigned in 1922. His work on the education authority was important in focussing his attention on social issues, such as the feeding and clothing of necessitous children, and helped shape his later attitudes to the problerns of poverty and unemployment.

With a regular source of income Maxton decided to marry Sissie (née McCallum), the daughter of John McCallum, master wright, in June 1919. Sissie Maxton was not a physically strong woman: a bout of rheumatic fever had left her with a weak heart, and her condition was in no way improved by their council house in Garngad, one of Glagow’s poorest areas.

To be near his wife, Maxton resigned his post as Scottish organiser and became secretary of the Glasgow ILP Federation in 1920. The following year a son was born. However, the boy, James, was seriously ill for a year and in need of constant attention. Nursing him almost night and day drained the life from Mrs Maxton. As the child grew in strength, she grew weaker and fell seriously ill herself. A few days later she died. The effect on Maxton was profound and something from which he never fully recovered. All that saved him from total collapse was his work and his love for his child.

Parliament

Following the death of his wife in 1922, Maxton was elected to parliament in the general election of that year, defeating his old rival, MacCallum Scott, by 7,692 votes. Maxton held the seat thereafter until his death in 1946. So popular was he with his constituents that in the 1929 general election his expenses totalled a mere £75 1s 6d, which gave rise to the saying in Bridgeton that they “didn’t count his votes, only weighed them”.

However, the breakthrough in 1922 for the ILP in Glasgow was a sensation. Along with the other Clydeside MPs, Maxton was given a rousing send-off at St Enoch’s Station.

On reaching Westminster one of the first acts of the new men was to play a vital role in the election of Ramsay MacDonald as leader of the Labour Party. Although Maxton had admired MacDonald’s stand against the war, he, in contrast to Kirkwood and Shinwell, spoke out against attempts to make him leader, and instead argued in favour of Wheatley. Wheatley’s anonymity, however, made him a most unlikely candidate and MacDonald was elected. That Maxton should turn to Wheatley as a potential leader of the Labour Party was an example of the high esteem in which Maxton held him.

On reaching Westminster one of the first acts of the new men was to play a vital role in the election of Ramsay MacDonald as leader of the Labour Party. Although Maxton had admired MacDonald’s stand against the war, he, in contrast to Kirkwood and Shinwell, spoke out against attempts to make him leader, and instead argued in favour of Wheatley. Wheatley’s anonymity, however, made him a most unlikely candidate and MacDonald was elected. That Maxton should turn to Wheatley as a potential leader of the Labour Party was an example of the high esteem in which Maxton held him.

In fact, Maxton once claimed that “John is my leader – I follow John”. But Maxton was no junior partner as in a later statement he said to Wheatley, “You will find me the trickiest leader you ever tried to lead.” In reality Maxton and Wheatley were complementary: the former, the missionary and orator; the latter, the shrewd and practical politician. It was Wheatley’s task to devise the strategy and tactics, and to detail the political programme; it was Maxton’s task to win popularity for it and to expound its general principles to the working class.

Without Maxton, Wheatley would never have achieved his eminence in the Labour movement nor would his schemes have gained so much support. Without Wheatley’s advice and guidance, Maxton may have ended his days as just another orator, outstanding maybe, but like AJ Cook lost in the political wilderness.

In parliament, and in the smart London society, the Clydesiders sensationalised their political opponents by refusing to socialise with them, neither did they accept invitations from rich Labour members. In fact, Maxton, Campbell Stephen and George Buchanan lived a rather solitary existence, firstly in Pimlico, and later in Battersea, their main entertainment being long chats with, in Maxton’s case, a copious supply of coffee and cigarettes, to which he was addicted. However, none of the three touched alcohol.

Maxton also outraged and moved the Commons in 1923 with his famous ‘murderers’ speech. It was made in response to Conservative support for a government motion to cut health grants to local authorities. Maxton said that the outcome would be the death of children. Clearly with the memory of his own child’s illness and his wife’s death at the forefront of his mind, and his experience on the GEA, nearly overcome with emotion, he accused the Tories of being murderers.

When Conservative Sir Frederick Banbury objected, Maxton called him the worst murderer of all. On an order from the Speaker to withdraw his remark, Maxton refused. Standing his ground for half-an-hour until, overcome by physical exhaustion, he sat down, only for his place to be taken by other Clydeside MPs and the charge repeated. All – Maxton, Buchanan, Wheatley and Stephen – were suspended.

On 30 July, after four weeks’ suspension, they attempted to force their way into parliament but were prevented by the police. Two days later an embarrassed Stanley Baldwin managed to secure an end to the ban. By now Maxton was, perhaps, the most popular member of the ILP, and the leading spokesman of the left wing of the ILP.

‘Socialism in Our Time’

This drew him into conflict with ILP chairman Clifford Allen. What separated the men at a social level was Maxton’s “difficulty in extending his spontaneous friendship” towards “frigid, middle class intellectuals”, which he considered Allen to be.

At a political level, it was Maxton’s support for no compensation in the event of land nationalisation at the 1924 Labour Party conference which strained relations between them to breaking point. Allen was in favour of compensation, and had been a member of the ILP commission which reported in favour of compensation to former owners. This was accepted at the ILP conference in York earlier in 1924, but Maxton disregarded the decision and voted accordingly in favour of no compensation.

The climax was reached when at an NAC meeting in October 1925 when Maxton proposed that MacDonald no longer be editor of the Socialist Review. This was approved and Allen immediately resigned his chairmanship, which was filled temporarily by Fred Jowett until Maxton’s election, by a majority of 500 votes, at the 1926 ILP conference.

Maxton held this position until 1931 and, after a three-year respite, again from 1934-9. Maxton’s acceptance speech outlined in broad terms his idea of what the ILP, as a socialist organisation, should be doing and what his role in this ought to be. He said:

“The ILP’s duty is to hold the ultimate ideal [of socialism] clearly before the working class movement… Political success for the Labour Party is a certainty, but political success itself is a poor end unless, behind the parliamentary majority, there is a determined revolutionary socialist opinion. It will be part of my duty to try to make as far-reaching as possible this feeling which I believe is the feeling of the party.”

To realise the ideal it was necessary to win over the Labour movement to the acceptance of ‘Socialism In Our Time’. The programme was first devised in 1925 under the heading of the ‘Living Wage’ and called for monetary controls, the nationalisation of banking, coal mining, electricity and railways, bulk purchase of raw materials, and the institution of family allowances. To rally the workers to the slogan, the ‘myth’ of a living wage was held out to them as an achievable goal. However, it was recognised by the leading party members as “unachievable in a capitalist society”, and therefore adopted “to force a conflict in which the system would be destroyed”.

But when the living wage programme was published in 1926 this notion was dropped in favour of the under-consumptionist theory of JA Hobson as means of avoiding economic crisis and unemployment. Maxton accepted this theory uncritically and continued to espouse it enthusiastically until his break with gradualism following the publication of the Cook/Maxton manifesto of 1928. However, the ILP programme failed to gain acceptance in the Labour movement.

Although a bold strategy to the leaders of the Labour Party it was still a gradualist programme linked to erasing the ‘defects’ of a capitalist society; as such it was criticised by the communists. Maxton was no Bolshevik revolutionary even though he had supported the CPGB’s affiliation to the Labour Party in 1925. To Maxton the achievement of socialism did not involve “a violent and catastrophic revolution”, on the contrary, it would be won by “the peaceful and orderly transformation of society”.

His insistence, therefore, on constitutionalism put him directly at odds with the Bolshevik and, hence, CPGB view of the violent overthrow of capitalist society. In spite of his theoretical differences with the CPGB, it did not prevent Maxton advocating co-operation with it, or its leaders.

Another ideal which Maxton was in favour of in his early days in parliament was Home Rule for Scotland. Maxton was for a time a prominent member of the Scottish Home Rule Association and spoke under its auspices on many occasions, even though in 1919 the Scottish Council of the Labour Party ruled this incompatible with membership of the latter body.

When in 1924 Buchanan’s Home Rule Bill came before Parliament, Maxton spoke at a rally in St Andrew’s Hall, Glasgow, in support, declaring that he would “ask for no greater job in life (than to transform) the English-ridden, capitalist-ridden, landlord-ridden Scotland, into a Scottish socialist commonwealth”.

Over the years Maxton held to his belief in Scottish self-determination and independence, but in the 1930s he had grown less enthusiastic, saying that “a struggle these days for mere political liberty is out of date, whether it takes place in India, Ireland or Scotland”. Henceforth, the struggle was to be directed at imperialism as a system of exploitation in the hope that with the collapse of the empire socialist revolution would occur.

That Maxton had come to adopt a neutral position vis-a-vis national struggles by this time was a manifestation of his move towards revolutionary socialism and internationalism and his total rejection of gradualism and narrow nationalism. This ideological shift was the product of a growing disillusionment with the labour movement which began around 1926 and ended with disaffiliation in 1932.

To Maxton the Tory government’s handling of the 1926 General Strike had been an example of naked class rule. He himself was involved in the workers’ struggle, and on 2 May spoke at a meeting on Glasgow Green, where he advised the working class to support the miners, but at the same time warned them “not to take part in riots when they would become simply the victims of the forces of the state”. On the whole, except for a few isolated incidents, the workers displayed a great deal of discipline, and even more solidarity until betrayed by the general council of the TUC.

The Cook/Maxton manifesto

This defeat of the workers and, later, of the miners, created a mood of defeatism in the labour movement and generated a drive towards class collaboration as exemplified in the Mond/Turner talks of l927. Recovered from an operation on a duodenal ulcer, which had incapacitated him for longer than he wished, Maxton returned to the political scene determined to put the working class back on the offensive.

Along with Wheatley, William Gallacher and AJ Cook, he put his signature to the Cook/Maxton manifesto of 1928, which called for an unceasing war against capitalism. It was also highly critical of Labour leaders and the Labour Party’s programme. As such it represented a move away from the more moderate ‘Socialism In Our Time’ programme, and was in marked contrast to the moderation of the Mond/Turner talks. It was also a manifestation of Maxton’s “desperate desire” to “lead the ILP completely away from reformism”.

By appending his signature to the manifesto, Maxton, as chairman of the ILP, was virtually committing the party to a policy on which it had not been consulted. In reply to his critics’ charge of undemocratic behaviour, Maxton said that in signing he was “simply stating party policy and as time was short he did not feel it necessary to get preliminary endorsement”.

Although his action was later endorsed by the NAC, it was an example not only of Maxton’s lack of judgement and impulsiveness, but also an illustration of his occasional high-handedness. In the event the campaign failed to stimulate the ILP into action: the Scottish divisional council opposed it outright, while other divisional councils gave reluctant support. Only Lancashire was enthusiastic. However, the campaign fizzled out after a lack-lustre performance by Cook and Maxton at the opening meeting held in Glasgow’s St Andrew’s Hall.

The campaign against pluralism was not the only occasion on which Maxton was to play the autocrat. In October 1927 Maxton became chairman of the communist-dominated League Against Imperialism. At the League’s second congress, held in Frankfurt in July 1929, he said:

“There are elements in the ILP who do not support my anti-imperialist policy and tactics and my association with the League. They may even be a majority of the party, but I am chairman of the party and will fight for the adoption of a militant policy against imperialism, and those in the ranks of the party who wish a moderate reformist policy will be discarded.”

When ordered to reprint the speech in the ILP’s New Leader by the League’s international secretaries, Munzenberg and Chattopadhajaya, Maxton refused, and consequently was expelled.

The speech, although clearly showing Maxton’s undemocratic tendencies, also highlighted his dissatisfaction with gradualism, a feeling which was to intensify during the life of the second Labour government. In these years, 1929-31, Maxton became convinved that the “Labour government was not leading the country to socialism”, and therefore he resolved that it had no right to to “claim his continuing and abiding loyalty”.

The most obvious example of Maxton’s resolve was his stand on Margaret Bondfield’s Anomalies Bill of 1931 which intended, under the name of economies, to disqualify casual workers and married women from receiving unemployment benefit. Maxton and the other Clydeside ILP MPs forced an all-night sitting of the Commons on 16 July, but in the end had to concede defeat. Maxton said of his stand: “There has been a great coalition here but if I never do another thing in public life, I am glad that I stood here through the night exposing that united attack on the poor people.”

Shortly after this incident MacDonald formed a coalition government with the Tories and Liberals. This act of betrayal was the final proof to Maxton of the failure of gradualism. The following year he wrote in the preface to John Scanlon’s book, The Decline and Fall of the Labour Party, what he believed to be the fundamental weaknesses of Labour’s approach, and what he hoped would result from its fall, saying:

“To me their failure was due to a lack of complete faith in socialism … and their lack of belief in either the desire or the power in the working classes to achieve socialism… I firmly believe that out of the defeat that at present faces the working classes in their efforts for socialist liberation, out of the schism and faction there will develop speedily a new political socialist movement of the working classes which will be strong enough in faith, in morale and in personnel to achieve success where its predecessor failed.”

Disaffiliation

It was this explicit expression of disenchantment with gradualism, and the desire for a more militant organisation committed to the immediate implementation of a socialist programme, which caused relations between the official Labour Party and the ILP to deteriorate to such an extent that disaffiliation occurred in July 1932. However, the immediate issue on which the split took place was procedural rather than theoretical.

The action of the Maxton group in the Commons in voting against Bondfield’s Anomalies Bill brought a storm of protest from ILP MPs, with more than 100 of them signing a round-robin letter condemning Maxton’s leadership of the ILP and his irresponsible actions. These views were also shared by the PLP and the leadership, who demanded that the ILP end its status as a party within a party and adhere to Labour Party standing orders. If not, Labour threatened to withdraw official electoral backing and put up accredited Labour candidates at elections against ILPers.

In adopting this truculent position the Labour executive was supported within the ILP by Patrick Dollan and EF Wise. Another faction led by David Kirkwood supported the idea of conditional acceptance. Lastly, a group which included Fenner Brockway and the Revolutionary Policy Committee (RPC) advocated disaffiliation. A special conference held in early 1932 supported Kirkwood’s proposal, as did Maxton. However, at another conference held later that year in Bradford, Maxton changed his mind, as did the majority of delegates, and the motion for disaffiliation was carried.

Much has been made of Maxton’s decision to support disaffiliation. Most writers on the subject have tended to argue that Wheatley’s untimely death in 1931 forced Maxton, because of his poor quaities as a leader and his lack of undertanding in matters of theory and practical politics, to rely on and be led by the Marxist clique centred around Brockway and the RPC.

But while a strong case can be made for this view – Maxton was himself of the opinion he was more an agitator than a leader, and he did rely on Wheatley for political analysis – it fails to appreciate the vehemence with which Maxton held to the anti-gradualist position, or to his equally strong conviction that capitalism was on the verge of collapse and the economic crisis had created a radicalised working class. Therefore, he acted quite consistently with his theoretical assumptions, as Cole explains:

“Maxton, coming from Clydeside and conscious of the rising temper of the workers there and in other depressed areas as they felt the weight of the means test and of other measures of economy and repression, probably took the Labour Party’s election defeat to mean much more than it turned out to mean, and had hopes of building up the ILP into a mass party standing for a left-wing policy.”

Out of the pale of the Labour movement (the ILP had opted for a ‘clean break’ policy, until rescinded in 1934), the ILP suffered enormously. Membership rapidly declined, as did the number of branches, as many ILPers, particularly MPs, defected to the ranks of the Labour Party. The decision of the Bradford conference had effectively consigned the ILP to a process of irreversible decline.

Nevertheless, in spite of depleted resources Maxton and his parliamentary colleagues fought an obstructive campaign against the national government’s economic and social policies, particularly the means test. He also pressed forward the claims of the hunger marchers in the Commons, although he was never physically capable of leading the marchers.

In the aftermath of the 1934 mass unemployed demonstration in Hyde Park, Maxton was instrumental in getting the House to debate the issue of unemployment and a delegation of the marchers admitted to Downing Street, although MacDonald refused to see them.

In organising the unemployed, the ILP, under the influence of the RPC group, had worked in concert with the CPGB. The main aim of the RPC was to win over the ILP to membership of the Communist International and to this end negotiations for membership were entered into. Maxton was extremely tolerant of the RPC’s activities, perhaps because he was unaware of its real intentions, or because he did not understand the tactics it employed.

However, Cominterm conditions proved unacceptable, and with the USSR’s entry into the League of Nations and the 1934 change of policy to one of working with, rather than against, social democrats, the mood of the ILP changed. An RPC motion in favour of “sympathetic affiliation with the Comintern and continued collaboration with the Communist Party” was defeated, and the leading RPCers resigned.

United action with the CPGB was not outlawed, and on the initiative of Sir Stafford Cripps and his Socialist League, a new phase of unity opened in early 1937. This initiative had even less chance of working than had the earlier campaign of 1933-4, as relations between the CPGB and the ILP had soured since then. The main cause of strained relations was the ILP and, in particular, Maxton’s attitude to the international situation.

Maxton was a pacifist, but as one of his former colleagues said, he was a “political objector to war”, not a moral protester. When Italy invaded Abyssinia in 1935, Maxton opposed the ILP decision taken at their 1936 Keighley conference to campaign for working class sanctions against Italy on the grounds that they were indistinguishable from those imposed by the League of Nations, and in any case to support sanctions would be tantamount “to a declaration that there were serious differences – for a socialist – between the two sides”.

“It was not,” he argued, “a matter of support or non-support, of assessing praise or blame, since the struggle was between two rival dictators.” And although defeated by 57 votes to 70, his refusal to accept the decision and his offer to resign as leader brought a compromise solution and a party poll on the issue. This produced a three to two vote in his favour, but was another example of Maxton’s undemocratic behaviour.

Spain and after

However, when the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, Maxton eschewed pacifism and took a determined stand with the Spanish republicans in their struggle. He was prepared to fight with the International Brigade, but was unable to find a doctor to pass him fit. Although his action in this instance may seem a contradiction, Maxton argued that Abyssinia had been an imperialist/capitalist struggle; Spain, on the other hand, was a workers’ struggle.

Eventually, he did go to Spain in September 1937 to secure the release of some of his ILP colleagues imprisoned by the Communist-controlled Spanish government. He was also able to use his influence with the British government to secure the release of Joachim Maurin, who had been gaoled by Franco, as a consequence of his republican activities, while a member of the Spanish parliament before the fascist uprising.

During these years the enmity was growing between the ILP and CPGB, particularly over the former’s support of the POUM in the Spanish conflict and its condemnation of the Moscow show trials of the mid-1930s. Thus, when the unity phase was reconstituted in January 1937 it was a suspicious and uneasy alliance. And when Cripps’ Socialist League was proscribed by the Labour Party on 27 January, the second united front collapsed. The collapse of the second united front against fascism brought with it an invitation from Attlee to Maxton in early 1938 to rejoin the Labour Party, and which he agreed to accept.

But, as before, the problem lay in the acceptance of Labour’s standing orders and whether they could be amended to extend the conscience clause to allow ILP MPs to vote, if necessary, against the PLP. This was of especial importance to Maxton as he was opposed to rearmament. In 1938 Maxton congratulated Neville Chamberlain on his return from his Munich talks with Hitler as he was of the opinion that the prime minister had secured a ‘breathing space’ in which those forces mobilised for peace could exert their influence.

Although criticised by Fenner Brockway, Maxton’s stand was endorsed by the 1939 ILP conference. In the same year he resigned as chairman and also, along with the NAC, recommended calling for a special. conference to endorse a decision to re-enter the Labour Party. However, war intervened and nothing came of it.

According to his biographer he was not prepared to accept any limitations on his anti-war activity, although Brockway says he was prepared to enter the Labour Party and accept the standing orders. The correct version is difficult to ascertain, but when war did break out Maxton associated himself with Lansbury’s Parliamentary Peace Aims Group, which demanded an immediate end to the war and a negotiated peace. As the war progressed and peace intitiatives were largely ignored, Maxton became increasingly reticent in parliament and, in 1944, fell silent when he collapsed and was forced to undergo a serious operation.

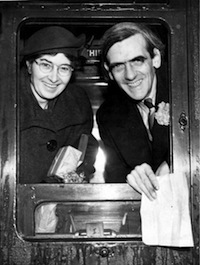

After this he never recovered his strength and spoke for the last time in the Commons on 6 December 1945. His last recorded statement was given on BBC radio’s weekly appeal programme, Good Cause, on behalf of Glasgow’s Victoria Infirmary. Thereafter, he spent his last months at Largs with his second wife, Madeline (née Glasier), whom he had married on 14 March 1935 and who survived him along with his son, James, who was by now a physician at the Victoria Infirmary, Glasgow.

Maxton not only spoke of revolution but he looked it too, with his long mane of black hair, cadaverous features, and tall spare frame. He was also one of the finest orators of the 20th century who combined passion with a sharp wit, a fine sense of humour, and tremendous personal charm. His integrity was never questioned by those in the Labour movement, and he never compromised himself by accepting favours from the ruling class.

In 1930 he turned down the offer of an honorary LL.D degree made to him by JM Barrie, then chancellor of the University of Edinburgh. In parliament he conducted himself in a noble and generous manner, acting with fairness and consideration even towards his political opponents. Winston Churchill described him as “the greatest gentleman of the House of Commons”. Outside of the House his attitude was no-different. Although his actions may have endangered his political position, Maxton visited Oswald Mosley in Brixton Prison when he was gaoled for his fascist activities, and obtained a resident’s permit for Trotsky in the Channel Islands.

In spite of his humanitarianism and other fine qualities, Maxton was prone to bouts of excessive emotionalism and sentimentality which clouded his judgement on occasion. Intellectual indolence was another of his failings and this increased his reliance on others to provide the theoretical underpinnings of many of his utterances. Although he was addicted to westerns and detective novels, Maxton did little serious reading apart from his early study of Marxism. As one political commentator said of him, “Maxton is a man of great … intelligence… But he lacks application.”

Lacking, then, in intellectual vigour, and failing to pursue study outside of a cursory reading of Marx, Maxton was susceptible to theories, such as the collapse of capitalism, which contradicted his humanistic view of socialism and the individual. It also makes it difficult to argue that there was a coherent political philosophy espoused, or held to, by Maxton outside of vague generalisations. He also lacked the business acumen and man management of Wheatley. And one finds it difficult to disagree with the verdict that he was just an orator.

However, he was a special kind of orator, one who inspired human beings to work and struggle for socialism by his devotion and example. His vision of socialism as a humane society of freely producing human beings provided the inspiration for a generation of young British socialists. His challenge to the Labour Party in 1928, that it could not “run capitalism any more successfully than Baldwin and the others”, still awaits its answer.

However, he was a special kind of orator, one who inspired human beings to work and struggle for socialism by his devotion and example. His vision of socialism as a humane society of freely producing human beings provided the inspiration for a generation of young British socialists. His challenge to the Labour Party in 1928, that it could not “run capitalism any more successfully than Baldwin and the others”, still awaits its answer.

Maxton died on 23 July 1946 at his home in Largs. His body was cremated three days later at the Glasgow crematorium. The funeral service was non-religious and was conducted by Sir Hugh Roberton and his Orpheus Choir. Maxton left an estate valued at £1,062. There is a portrait of him by Sir John Lavery in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, and a head sculpture by Lady Kennet in the Glasgow City Art Gallery.

—-

This article was originally published in Scottish Labour Leaders 1918-1939: A Biographical Dictionary, edited by William Knox, 1984, and is re-printed with permission of the editor to whom we owe many thanks.

See also: ‘James Maxton – Socialism’s Great Crusader’ by Gordon Brown and ‘The Will to Socialism’, written by Maxton in 1927.