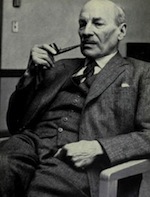

Clement Attlee had a very long and productive political life. DAVID CONNOLLY provides a brief sketch of the man who first learned his politics in the ILP in the early years of the 20th century.

“I would put the difference between Conservative and Socialist plans this way. Conservatives would plan this country on the model of the old English village. There would be a large house for the squire, a few of fair size for the parson, the gentry and farmers, and a row of cottages for the workers. The squire would rule. In the Socialists’ plan there would be no little cottages and no large private houses. All would be reasonably well housed, while the only large buildings would be those owned and used by the community, in one of which the villagers would meet to settle their common affairs.”

Clement Attlee, The Will and Way to Socialism (1935)

Clement Richard Attlee was born on 3 January 1883, the seventh of eight children in a deeply religious, Anglican, middle class family. His father, Henry, was a solicitor and a Gladstonian Liberal. His mother, Ellen, ran the household with three servants, plus a cook and a gardener. She was educated to a high level for a woman at that time and, politically, she was a Conservative. Due to childhood illness the young Clement was educated at home where he developed a love for cricket and its statistics.

Later he went to Haileybury public school and in 1901 to University College, Oxford, where he enjoyed university life and was seen as a steady student. At this time he described himself as an “ultra Conservative”. So what happened to change his views?

In October 1905, he visited the Haileybury Club in Stepney with his brother, Lawrence. The club, run by the public school to help poor boys in the East End, was like the Army Cadets but with social and educational aims, and all former Haileybury pupils were expected to make a contribution to its work.

Here Attlee was confronted by the reality of mass poverty. Influenced by another brother, Tom, he quickly came to reject the establishment view that the poor were responsible for their own plight and became convinced that collective action by the state was necessary to tackle the problem.

The two brothers attended a few Fabian Society meetings but found them unsatisfactory and in January 1908 Clem was recruited by Tommy Williams, an East End wharf keeper originally from Wales, to join the local branch of the more radical Independent Labour Party. Attlee quickly became the secretary of Stepney ILP and was appointed manager of the Haileybury Club where he lived for the next seven years.

As a result of his connections with the London School of Economics he was involved in research for the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws which, strongly influenced by the Webbs, argued that it was the state’s responsibility to abolish poverty.

As a figure of growing importance in the local Labour movement, Attlee spoke at numerous open meetings, supported demonstrations, advised workers in dispute, and organised local elections, his aptitude for administration and organisation coming to the fore.

With the onset of the First World War, his brother Tom became a conscientious objector and was imprisoned in Wormwood Scrubs, but Clem had no doubts. He did not agree with the ILP’s opposition to the conflict and joined the South Lancashire Regiment as an officer. He saw action many times at Gallipoli and also in France in 1918.

Interestingly, he considered Churchill’s military strategy in relation to Turkey to be excellent, but its execution woeful. Taking great care not to lose lives unnecessarily, he was respected by his men and eventually promoted to the rank of major. There was a toughness about him and on one occasion in France he drew his revolver threatening to shoot a fellow officer for not going ‘over the top’ with his men, although fortunately he didn’t have to carry out the threat.

Between the wars

With the end of the war and the extension of the franchise to all working class men, Labour won control of Stepney council in 1919 and Attlee became the mayor, defusing potential conflicts between Irish and Jewish members of the Labour group with his able diplomacy. He supported George Lansbury during the Poplar revolt of 1921, a position strongly opposed by Herbert Morrison, then Mayor of Hackney and his long-term critic.

Attlee was elected as MP for Limehouse at the 1922 general election, the first Oxford graduate to sit on the Labour bench. He became a parliamentary secretary to Ramsay MacDonald (who had opposed the war).

That year he also married Violet Millar, who was 13 years his junior, the start of what was to be a happy marriage. She came from the same social background and became respected in the Labour Party for her caring approach, although by instinct she did not share Attlee’s politics.

In the minority Labour Government of 1924, he became Under Secretary at the War Office, working closely with Jack Lawson, the former Durham miners’ leader whom he greatly admired. It is no coincidence that between 1934 and 1956 Attlee spoke at the Durham Miners’ Gala on nine occasions.

When Labour was in opposition Attlee was a regular Commons speaker, always making well-informed contributions. However, as James Maxton and the ILP leadership became increasingly confrontational to the parliamentary leadership, Attlee began to loosen his ties with the organised left.

In 1927, much to his irritation, he was appointed as one of the Labour representatives on the Simon Commission to look at the future of India. He was not happy with this as the role took him away from parliament for two years, but he did his duty and, in the process, became familiar with a country that was to present his post-war government with one of its major issues.

In 1929, Labour became the largest party in parliament and for a second time formed a minority government. Attlee’s involvement in India meant he did not join the government until May 1930 when he replaced Oswald Mosley as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

Like most Labour MPs, Attlee rejected MacDonald’s defection to the Tory-led National Government in 1931 and he reflected on his wartime experience when he spoke to his fellow Labour MPs: “Some of you have been soldiers, no doubt. You will know that there is only one occasion when a soldier is justified in disobeying orders. That is when his senior officer goes over to the enemy.”

After Labour’s election debacle, when the party returned only 46 MPs, George Lansbury became leader with Stafford Cripps and Attlee as his deputies. Attlee’s promotion was the result of so many potential rivals losing their seats in the election, and during the first four years of the National Government he was very busy speaking on a wide range of subjects yet always willing to help his less experienced colleagues make their mark. According to the historian David Howell, Attlee was always “close to the party’s centre of gravity”, which at the time was moving leftwards.

The Italian invasion of Abyssinia led to George Lansbury’s downfall at the hands of Ernie Bevin, general secretary of the Transport and General Workers Union, at the 1935 Labour conference. Lansbury’s pacifism and opposition to sanctions against Italy made his leadership untenable, as he well understood.

In the leadership election that followed Attlee stood against Morrison and Anthony Greenwood, and won. Hugh Dalton, one of the many Labour MPs who lost their seats in 1931, said, dismissively, “a little mouse shall lead them”, while Beatrice Webb declared the new leader to be “irreproachable but colourless”.

In March 1937, the party published “Labour’s Immediate Programme” calling for the nationalisation of the coal industry, power, transport and armaments, policies that foreshadowed what was to come.

While initially supporting the policy of non-intervention in Spain, Attlee quickly reversed this position without ever clarifying a positive policy in support of the republic. Indeed, Labour’s stance on Spain was full of equivocations and they failed to issue a policy statement, much to the disappointment of many party members. Attlee did lead a delegation to Spain, which included Philip Noel-Baker, in December 1937, but overall the concern to avoid a more general conflagration, and the need to manage internal divisions on this issue, left him looking weak.

War and after

Only very slowly did the leadership come to recognise the need for rearmament against the growing threat of fascism, memories of the First World War still vivid in the minds of so many. As late as 1938, Labour opposed an increase in the defence estimates.

However, with the onset of war, and following the departure of Chamberlain after the disastrous Norwegian campaign, the Labour leadership agreed to join the wartime coalition in May 1940 – but only after consultations with the national executive committee and the endorsement of conference which was taking place in Bournemouth.

Attlee became Deputy Prime Minister and Labour was given two seats in the War Cabinet – Ernie Bevin became Minister of Labour and Herbert Morrison started as Minister of Supply before taking up the post of Home Secretary.

In the crucial Cabinet debates that followed the evacuation from Dunkirk, both Churchill and Attlee resolutely rejected proposals from Lord Halifax and Chamberlain to seek a negotiated settlement with Hitler via the offices of the Italian government. Their defeatist and irresponsible hope was that such a settlement in Europe would at least leave the British Empire intact.

Attlee’s role in the Second World War is much underestimated. Apart from Churchill, he was the only continuous member of the War Cabinet throughout the conflict. He also served on the Defence Committee, chairing the committee as it dealt with the Home Front. This did not give him a high profile but, crucially, behind the scenes, he was the government’s key co-ordinator and a far better chair of the Cabinet than Churchill, who could cause confusion even when sober.

Fortunately for him, Attlee had the capacity to sleep through the bombing, normally taking both breakfast and dinner at the Oxford and Cambridge Club close to Downing Street. In short, he kept the government show on the road, and was an indispensable figure, although few, especially Herbert Morrison, saw him as a future peacetime prime minister.

Public opinion had begun to move against the Tories as early as the summer of 1940 and, as the state began to run the war effort effectively, organising both labour and capital in the interests of victory, the perception of Labour’s competence grew. Expectations of post-war security were fuelled by the publication of the Beveridge Report in early 1943 with many Labour MPs voting for its implementation immediately after the end of the conflict.

This was against the advice of their leader who urged them to have a greater regard for the immediate need to maintain the stability of the coalition given the strong Tory opposition to Beveridge. This was undoubtedly a difficult and awkard position for Attlee to take but one he felt duty bound to express, however unpopular with his backbenchers.

The general election held in July 1945 saw Labour win 48 per cent of the vote, securing a huge and unexpected majority. Remarkably, even after the result was known, Herbert Morrison, aided by Ellen Wilkinson, was conspiring to replace Attlee with himself, although their disloyal machinations quickly petered out.

Wilkinson was the one woman in the new Labour cabinet, a strongly opinionated Minister of Education. Attlee, as ever, proved to be an able chair, carefully summing up the arguments before declaring the outcome of a debate. His approach was flexible and phlegmatic, knowing that he had the support of the key trade union leaders on the major issues of the day as well as a high degree of trust from Labour Party members and voters.

That Labour government set the parameters of politics for the next 30 years and the list of what it achieved includes: Family Allowances, National Insurance, payments for industrial injuries, National Assistance, the implementation of the 1944 Education Act, raising the school leaving age to 15, the provision of free school milk, the National Health Service and, in 1947 alone, the construction of 139,000 council houses.

In addition, Labour nationalised the Bank of England, civil aviation, cable and wireless communications, coal mining, road haulage, canals, railways, gas and electricity and, eventually, the iron and steel industry. The government also demobilised the armed forces in an orderly manner, although Attlee did support the secret development of nuclear weapons, a subject never raised nor discussed in the House of Commons between 1945 and 1950.

Stark choices

But Labour faced major financial problems from the outset. The war had cost about a quarter of the national wealth and Britain was left with a shrunken export market and an escalating import bill. The national debt trebled in size. During the war, survival had depended on the American Lend-Lease programme which was not renewed by President Truman in 1945.

As the dominant economic power the American aim was to expand its markets by ending Imperial Preference, so the government was faced with a stark choice – either to seek further loans with conditions attached or go-it-alone. John Maynard Keynes wrote that to do the latter would lead to more stringent rationing for the next three to five years than had been the case during the war, state planning of all foreign trade “on the Russian model”, and military withdrawal from the empire. Would the British people have supported such a radical option?

Labour’s leading figures were acutely aware of the tough options facing them but were not willing to have a public debate on the matter and, after considerable difficulty with the Americans, negotiated a further loan from the United States. This was designed to end the leading role played by sterling in world trade and gave America what it wanted – access to the markets of the British Empire. It significantly weakened Britain’s control of international trade but did so without destroying the country economically which, with the emergence of the Cold War, was obviously not in America’s interest.

As a measure of the dire nature of the economic situation, bread rationing was introduced in July 1946, something which had never happened during the worst days of the war itself. The next day, Labour lost 10,000 votes in a by-election in Bexley where Edward Heath was the Conservative candidate. Nevertheless, the loan enabled the government to continue with its social programme at the political cost of subservience to American foreign policy, something which continues to this day.

The years 1945-47 were the high point of the Attlee government. After that, it faced ever increasing problems and growing discontent with Attlee’s leadership, although he faced no serious challenge, largely because there was no widely accepted successor and he had the support of the trade union leadership, plus his own deft handling of the situation.

In his excellent mini-biography of Attlee, the historian David Howell describes the 1945-51 period thus:

“What emerged was a social democratic modification of capitalism. This met long-standing demands for welfare, full employment and, for some, decent and affordable housing – in other words treatment as respectable citizens. Whether most Labour supporters wanted much beyond these essential priorities is debatable. The outcome, despite the austerity, was a decisive advance over most pre-war working class experiences. These achievements seemed secure.

“Yet much remained largely unchanged – institutions and culture, the distribution of wealth and power. The old order had been modified but had not disintegrated. That the coal owners had gone, but the public schools remained, was perhaps an appropriate comment on the politics of Mr Attlee… but a much more thorough reconstruction of society would have necessitated, not the existing leadership acting differently, but a very different leadership.”

Despite polling over one and a half million more votes than the Conservatives, the 1950 election resulted in a majority of just five seats for Labour and with the collapse of the Liberal vote the following year, the party went into opposition to face years of bitter internal dispute. Keen to ensure that Morrison would not be his successor, Attlee held on as party leader until 1955 when, to his satisfaction, Gaitskell defeated both Morrison and Bevan to take over.

Attlee then went willingly to the House of Lords, which he attended assiduously, travelling by train from Essex while avidly reading detective novels in his regular seat. His last public act was in 1965 as one of the bearers of Churchill’s coffin, and at the end of the service, having done his duty, he sat on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral, worn out and exhausted.

Clement Attlee died on 8 October 1967. His low-key funeral was held in Temple Church and although he was an agnostic he nevertheless ensured that the lesson was taken from the Book of Revelations, St John’s vision of ‘The New Jerusalem’. His ashes are buried in Westminster Abbey a few feet from the flagstones commemorating Ernie Bevin and the Webbs.

I am sure that Attlee would be deeply troubled by many aspects of present day society and, without indulging in nostalgia, we would do well to remember the optimistic and humane aspirations of the immediate post-war era captured so well by Lewis Silkin, the Minister for Town and Country Planning, speaking in the House of Commons in 1946 about the proposed New Towns:

“The planning should be such that the different income groups living in the new towns will not be segregated, no doubt they may enjoy common recreational facilities, and take part in amateur theatricals, or each play their part in a health centre or community centre. But when they leave to go home I do not want the better off people to go to the right, and the less well off to go to the left. I want them to ask each other, are you going my way?”

A good question for Attlee’s time – and an even better one for our own.

—

David Connolly is chair of the ILP’s national administrative council. This article is based on a talk given in April 2013 to the Durham Branch WEA Study Group, ‘Politicians, Thinkers and Activists’.

See also: ‘Attlee, the ILP and Romantic Tradition’, the first Clement Attlee Memorial Lecture given by Jon Cruddas MP in October 2011.

‘From Attlee to Miliband: Can Labour and unions face the future?’, the 2013 Attlee Memorial Lecture, delivered by TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady.

And: ‘Clement Attlee and the foundations of the British welfare state’, the 2014 Attlee Memorial Lecture, delivered by Labour’s Shadow Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Rachel Reeves and her advisor, Martin McIvor.

6 February 2014

Just a footnote on the Ernie/David discussion. Some New Town developments had complexities. When Peterlee was established in County Durham, it placed a block upon developments in surrounding mining collieries. This may have had certain drawbacks at the time, leading to a decline in established communities. Then as the pits closed, those that remained became more cosmopolitan, with miners travelling in to work from Peterlee and from the villages who had lost their pits. Then, when the pits were finally closed, the former mining communities went into decay. Many former colliery houses were then knocked down and social problems grew. Peterlee has also suffered from the destruction of jobs in the area, but it will have survived in better ways than most of its surrounding former colliery villages. So whilst Silkin’s vision in Peterlee’s case was not unproblematic, in the long run the development may have turned out to have been the best option. It shows the importance of having a socialist vision. If everything did not work to prefection at the time, the achievements of Clem and company show us the shortcomings of the current Labour Movement and (related to modern circumstances) show us what is worth striving for.

David is to be thanked for showing the road that Clem followed. Sometimes, the history of the Labour Movement can shape our current asperations. My own excuse for the Peterlee intervention is that in 1959 and 1960 I was secretary of the Peterlee and District Fabian Society. At Easington Colliery we once ran a day-school on steel nationalisation which was attended by 78 people. We were living off the inheritence of Clem and company.

25 January 2014

Thanks for your comment Ernie and I’m pleased that you picked up on the Silkin comment which, almost in a non-political way, captures the spirit of the time.

The planning of the new towns was controversial with some people (there was a big campaign against it at Stevenage) and subsequently it has been condemned for its paternalistic approach. The results have been mixed and from my own experience I would say that Washington, one of the later new towns in the North East, is now highly socially segregated but at least the post war intention to improve life for the poorest was there, in stark contrast to our present rulers.

The next generation of Silkins, Jon and Sam, served in the Callaghan government and Jon was the third (forgotten) candidate in the momentous Benn / Healey Deputy Leadership contest in 1981.

19 January 2014

A superb article on Clement Attlee and his post-war Labour administration, which stands in stark contrast to the timid (some might say cowardly) response to the banking crisis, big money fraud, national bankruptcy and fiscal deficits by many of today’s Labour politicians, unrepentant Blairites and free market apologists.

What is so striking about Attlee’s political philosophy, summed up brilliantly in the “are you going my way?” quote (by Town and Country Planning Minister, Lewis Silken), is his approach to social exclusion and his determination to ensure that all UK citizens shared the fruits of capital accumulation and what a modern industrial society has the capacity to provide. What a contrast to David Cameron’s “big society”, George Osborne’s “we’re all in it together” and Ed Miliband’s One Nation Labour political spin.

What the Attlee experience informs me is that there is an alternative to neoliberalism and to the obscene imbalances in UK society, and that declarations by politicians about wanting fairness and social justice is dishonest bunkum and a cop-out unless supported by realistic policies focused on challenging the forces of capital and establishment interests, and aimed at bringing about fundamental social change.

Not easy, by any means, but the Attlee approach to politics shows it can be attempted and much can be done. But whether or not this is a project that today’s intake of (look-a-like) Labour politicians are capable of taking on is questionable.